6 April 2023

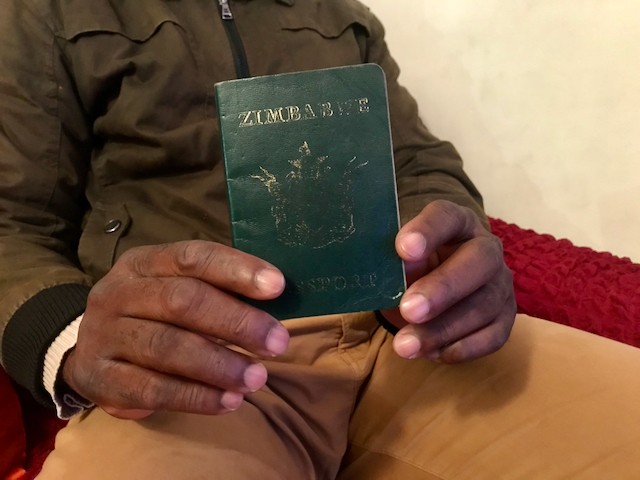

The decision to terminate the Zimbabwean Exemption Permit will be challenged in the Pretoria High Court next week. Archive photo: Tariro Washinyira

When Minister of Home Affairs Aaron Motsoaledi terminated the Zimbabwean Exemption Permit (ZEP), he told its 178,000 holders that this would enable them to “regularise” their stay in South Africa through the Immigration Act’s mainstream visa system, now their only chance at remaining in South Africa legally when the ZEP expires on 30 June 2023.

In reality, though, regularisation under the Immigration Act has always been out of reach for most ZEP holders, because of the legal and practical barriers that clutter the road to a mainstream visa. Regularisation was out of reach when the ZEP was first introduced as the “Dispensation for Zimbabwe Project” in 2009, and it remains out of reach today, less than a week before Motsoaledi’s decision to terminate the ZEP will be challenged before the Pretoria High Court between 11 and 14 April 2023.

Without a ZEP, most of its former holders will have to try their luck at applying for a general worker’s visa, which allows those excluded from Home Affairs’ unforgiving critical skills list a chance to remain in South Africa – at the Director General’s discretion. The problem, though, is that applicants for a general worker’s visa must first convince the Department of Labour that no South African can do the job for which the visa is sought. This will be difficult to do for most ZEP holders, who arrived as political refugees fleeing Zimbabwe’s tragic collapse in 2008.

It is possible to apply to Home Affairs for this exacting requirement to be waived before applying for a general worker’s visa, but at this point on the already improbable road to regularisation, Home Affairs’ processing capacity only further dampens hope. In September last year, Home Affairs reported the receipt of just 9,000 waiver applications from ZEP holders and did not reveal how many of those were followed by successful applications for mainstream visas. And despite touting a team dedicated to the influx of applications from ZEP holders, Home Affairs conceded that they did not have the capacity to deal with them all by the ZEP’s initial termination date – 31 December 2022 – and granted ZEP holders a reprieve to the current deadline of 30 June 2023.

The situation has not much improved. Last week, Home Affairs issued a circular in which it announced an extension to 31 December 2023 for all existing long-term visas (which do not include ZEPs) where holders are still waiting for waiver or visa applications to be processed. In its circular, Home Affairs discloses a staggering backlog of nearly 63,000 visa applications, behind whom all waiver applicants must stand. Adding ZEP holders to the queue just deepens the administrative catastrophe that stands between them and regularisation before the ZEP terminates.

Home Affairs would have picked up the legal and practical barriers to regularisation if only Motsoaledi had consulted with ZEP holders to understand whether his decision could rationally serve to regularise their stay in South Africa. But he did not even try, denying ZEP holders their basic legal right to a fair hearing before making a decision that will irrevocably damage their lives. The result is a decision to cancel the ZEP, blind to the untold hardship that former holders will have to endure.

Indeed, it is Motsoaledi’s refusal to consult with ZEP holders before cancelling the ZEP that underpins this month’s court proceedings. Since late 2021, Home Affairs has faced applications from the Zimbabwean Exemption Permit Holders Association, the Helen Suzman Foundation (HSF) and the Zimbabwean Immigration Federation challenging the lawfulness of Motsoaledi’s decision to terminate the ZEP – all of whom take issue with his lack of consultation before cancelling the ZEP.

Responding to HSF’s allegations that he did not consult with ZEP holders before making his decision, Motsoaledi points to a paltry email address appended to the end of a public announcement of his decision to terminate the ZEP. A sample of roughly 400 emails was shared in court papers, supposedly to illustrate the bona fides of Motsoaledi’s attempt at consultation. Instead, they reveal a chorus of confusion and desperation from ZEP holders not knowing what to do next in the face of a decision already made.

And Home Affairs’ response? In all cases shared, it is auto-generated and shows that Motsoaledi had not envisaged that the information received would ever reach him, reading:

“We acknowledge the receipt of your email. If you are a ZEP holder then we will respond to you in due course. If you do not receive a response, please consult vfsglobal.com website for all visa and permit information.”

By now, the already strained nerves of ZEP holders may well be close to breaking point. For them, the logical result of Motsoaledi’s decision to terminate the ZEP has always been either to force them from South Africa or to leave them to languish here as undocumented immigrants. Regularisation under the Immigration Act as an alternative to this impossible choice is simply a mirage that will not cure the pain of losing the ZEP – not for its holders nor the South African communities in which they have lawfully built lives over more than a decade.

Views expressed are not necessarily those of GroundUp.