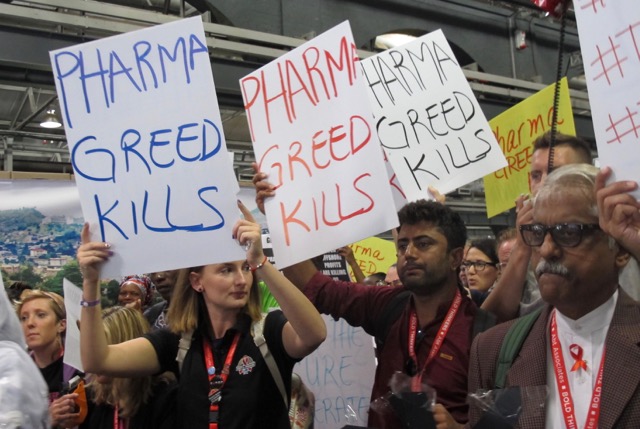

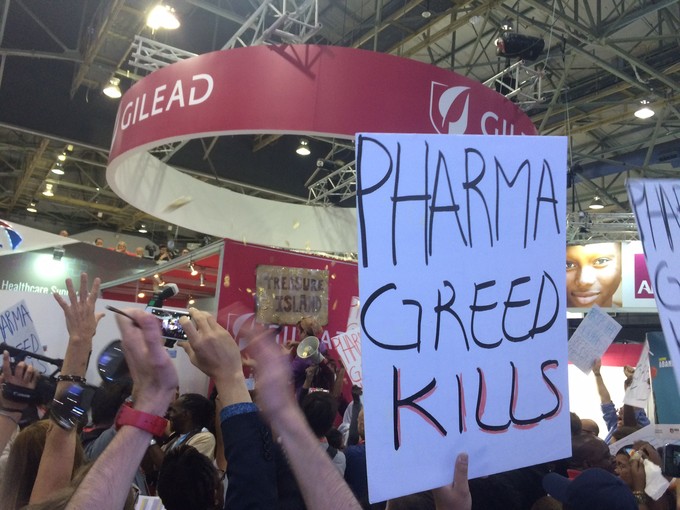

Protesters at the AIDS2016 Conference in Durban highlighted Gilead Science’s pricing of its hepatitis C drug sofosbuvir. Photo: Liz McGregor

28 July 2016

Delegates at last week’s international AIDS conference protested drug manufacturer Gilead Sciences, over the price of its extremely effective hepatitis C medication, sofosbuvir. Gilead’s booth at the conference was taped over with posters. “Kilead” was written over the company’s name.

In the United States the cost of sofosbuvir is $84,000 (R1.2 million). Since September 2014, Gilead has offered 101 developing countries what are called voluntary license agreements for generic versions of the medication. It would therefore cost approximately R13,500 in South Africa.

Sofosbuvir is often described as a ‘miracle cure’. When it is used for 12 weeks with at least one other hepatitis C medicine, it has a 95% cure rate and causes few side effects. This is much better than the previous treatment, which has a complicated 24 to 48 week regimen, a 50-70% cure rate and causes flu-like symptoms and lasting emotional problems in many patients.

The World Health Organisation estimates that hepatitis C infects 130 to 200 million people globally. It is spread through contact with infected blood, usually from injecting drugs or tattooing with shared equipment, unsafe medical procedures including blood transfusions and dialysis, from mother to infant and sexually — mostly between HIV-positive men who have sex with men.

Most of those who are infected will experience almost no symptoms for up to 20 years. However, approximately 80% of people develop chronic hepatitis C infection. This causes fatigue, depression, memory problems and liver disease. The WHO estimates that hepatitis C related liver disease kills 700,000 people each year.

Hepatitis C also comes in six different forms (or genotypes). While they generally cause the same symptoms, certain treatments only work for certain forms. The most researched form, genotype 1, is mostly present in the United States and Europe. Sofosbuvir has been approved to treat all genotypes.

Unlike hepatitis A or B, there is no vaccine to protect against hepatitis C. The decades long dormancy of the disease means that many people remain undiagnosed for their entire lives or until they have serious liver damage. For many developing countries, there are no accurate estimates of how prevalent the disease is.

Not much is known about the presence of hepatitis C in South Africa. According to a 2013 report from the National Institute of Communicable Diseases, approximately 1% of South Africans have hepatitis C. Many of them are also HIV-positive. The report also states that the lack of any national screening programme, research, or campaigns for the disease severely limits efforts to fight it. South Africa only started screening blood donations for hepatitis C in 1990.

In December 2015, a US Congressional investigation found that Gilead had set the cost of its treatment primarily to maximise profit, with no consideration for affordability. It also stated that Gilead did not consider the production or research cost as major factors in setting the price. Additionally, the report says that the company believed that setting a high price for the medication would allow it to set even higher prices for the next wave of their hepatitis C drugs.

Even after realising that the $84,000 price meant that most patients were unable to access the medication, Gilead refused to decrease it. While it did negotiate with public health care systems in some states, only five US state health care programs signed agreements to cut the price by 10%. The report says that only 2.4% of the 700,000 public health care enrollees in the United States were able to access the medication.

A study conducted by Dr. Andrew Hill, a pharmacologist at the University of Liverpool, estimated that the manufacturing cost of a full course of treatment for sofosbuvir was $68-$136 (less than R2,100).

Gilead has justified its high prices by arguing that treatment is less expensive than a liver transplant, and that their pricing is based on the value of the medicine, not how much it costs to produce.

Gilead also points to its efforts to market the drug to developing countries at a much lower cost. However, an expert in the field, speaking anonymously, raised concerns that such agreements often contain measures that violate patient confidentiality and undermine adherence, such as making people return empty bottles before they are given more medication, photographing people and asking them to present proof of citizenship. These measures are meant to cut down on “medical tourism” when people travel to other countries to receive medications at much lower prices.

By proactively forming these agreements, Gilead is able to maximise its revenue by ensuring that patients in other countries are forced to pay the extremely high prices. Additionally, Gilead avoids the possibility of these governments issuing a “compulsory license,” allowing them to override Gilead’s patent and cheaply manufacture generic versions of the drug. India had previously used compulsory licenses to increase the ease of access to cancer drugs.

Also, many middle-income countries, such as Brazil, China and Thailand, where millions of people have hepatitis C, were not offered voluntary licenses from Gilead, leaving them without access to affordable generic versions of sofosbuvir. Instead, these countries must buy treatment directly from Gilead, at much higher prices.