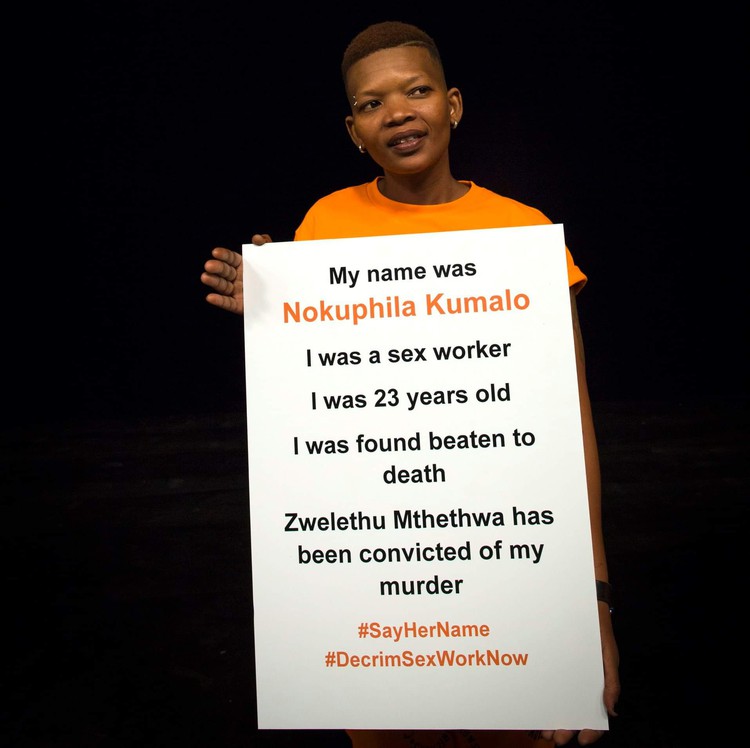

The Sex Workers Education and Advocacy Taskforce (SWEAT) petitioned for the Javett Art Centre to remove Zwelethu Mthethwa’s artwork. Photo supplied by SWEAT

7 October 2019

The Javett Art Centre at the University of Pretoria has been asked by various civil society organisations to remove Zwelethu Mthethwa’s artwork. Mthethwa is a convicted murderer who killed a 23-year-old sex worker, Nokuphila Kumalo.

Mthethwa, a well-known South African painter and photographer, kicked and stomped Kumalo to death, in full view of a CCTV camera, in Cape Town in 2013. During his trial, he claimed not to remember what happened because he was intoxicated. He chose not to testify or explain the reason for his rage. He was convicted of murder in 2017 and is currently serving his 18 year sentence in Pollsmoor prison.

The criticism of the gallery and petition to remove Mthethwa’s artwork from the exhibition titled All in Day’s Eye: The Politics of Innocence was started by Sex Workers Education and Advocacy Taskforce (SWEAT).

SWEAT said in its petition, which has close to 800 signatures, that the exhibition of Mthethwa’s artwork against the backdrop of gender-based violence in the country shows a “complete disregard of the trauma this and all other acts of violence” cause against women.

Lesego Tlhwale, advocacy manager at SWEAT, said the organisation did not think it is fair for a man convicted of murder to be given a platform and space to showcase his artwork. In a statement released on 2 October, SWEAT said it respected freedom of expression “as an essential constitutional guarantee that extends to the right to exhibit artwork”.

But it said it was asking the gallery to remove his artwork out of respect for Kumalo’s family, community and the violence against women in the country.

“As activists and institutions who believe in constitutional democracy, we accept that being offended or appalled is not a basis for the limitation of this critical right [to freedom of expression] … We believe that there is a need to communicate our zero tolerance to gender-based violence, including the consumption of art produced by perpetrators,” read the statement.

Tlhwale told GroundUp that the art space was allowed to practice activism in any form it wanted to but in doing so, it should respect other activists who have called out the use and promotion of artwork of a man convicted of murdering a women.

In a statement responding to SWEAT, lead curator of the exhibition Gabi Ngcobo said: “We would like to stress that there is nothing celebratory about the exhibition … our curatorial strategy is not one that endorses but one that rather seeks to reveal the hypocrisy that we often encounter in our field.”

She said the intention of the exhibition was to present “evidence” that would highlight how misogyny has played out in Mthethwa’s work over time. This was to be done through a visual essay that would open the space up to scrutiny using the example of Mthethwa’s work, “as it is our duty too, as black women in art spaces, to create platforms where these forms of violence can be exposed, challenged, and or criminalised”.

“We can see through his work, the perpetuation of violence against women. We therefore elected to utilise his work to present a psycho-social analysis that exposes his violent actions as not emerging out of the blue,” read Ngcobo’s statement.

But SWEAT said this justification was disingenuous. A conversation was still possible without making Mthethwa’s artwork the focal point, said SWEAT in it’s 2 October statement.

It said the public would not lose anything if the artwork was removed. But if it was not removed, an opportunity to send a strong message that artwork by people who murder women will not be exhibited will be missed.

“Our stance on this question is also clear: where there has been a conviction in [a] court of law, the artwork should not be displayed,” read SWEAT’s statement.

Director of the Helen Suzman Foundation, Francis Antonie says that Freedom of expression is guaranteed by the Constitution. But it is a highly contestable right as we have recently been reminded of in the old South African flag matter. “Two questions arise. Whose rights need protecting, and whose rights are being violated?” And in the case of the Javett Centre’s exhibition, how does this relate to the rights of curatorial independence coupled with contractual obligations, asks Antonie.

“But what of the rights to dignity of the family of Nokuphila Kumalo, who was so brutally murdered? And does this exhibition truly memorialise what she, and so many other women have had to, and continue to endure?” wonders Antonie.

“The rights issue in fact does not take us very far into addressing these questions or, indeed fully understanding the controversy,” he says. “The controversy surrounding the exhibition has all the hallmarks of a dilemma — that there is no right or wrong answer, only a preferred one. This may perhaps explain both the intensity and the sense of mutual incomprehensibility which some have noted.”

Antonie says: “No painting is simply about pretty flowers … it is also about the social context in which works of art are created, displayed, exchanged, celebrated or condemned.”

“How is this dilemma to be dissolved? By its nature it cannot be, but it may be able to be explored by bringing the different views together in a real and difficult conversation.”

Candice Breitz, an artist whose work is exhibited in one of the installations at the Javett Art Gallery, withdrew her work and requested that the gallery leave the monitor on which her work was displayed blank for the duration of the exhibition.

The withdrawal was made in solidarity with recent mass protests against gender-based violence, SWEAT, in memory of Kumalo, out of respect for her family and community and in acknowledgement of the thousands who are violently abused and killed as a result of gender-based violence, said Breitz.

She said it was not an attack on Ngcobo, who Breitz said has always been radical in her politics and who is one of the best curators in the country, but rather a gesture of solidarity to Kumalo’s family who were not consulted prior to the exhibition.

“Nobody that I know doubts the good intentions of [Ngcobo] or her curatorial research team in curating [Mthethwa] into an exhibition at the Javett Art Centre. It is not their intentions that are being questioned, but their judgment,” said Breitz in a statement released on 3 October.

She said Ngcobo’s decision to “come along and dust off Mthethwa” who has not been exhibited in contemporary art intuitions for the last two years following his conviction has offered a license for others who are invested in his work to bring it back into circulation and speculation.

“Because if Ngcobo, our country’s leading and most critical curator, thinks it is okay to offer wall space to Mthethwa again, then there will surely be a plethora of less well-intended collectors and speculators who will see fit to do the same,” said Breitz.

She said if Kumalo’s family and community thought it was too soon for Mthethwa’s work to reappear in the country’s most prestigious art institutions, their wishes should be respected.

She requested that a poster from SWEAT’s #SayHerName campaign be placed on the blank screen where her work was displayed and said she would be calling on other artists to do the same.

The poster reads: “My name is Nokuphila Kumalo. I was a sex worker. I was 23 years old. I was found beaten to death. Zwelethu Mthethwa has been convicted of my murder. #SayHerName #DecrimSexWorkNow.”

CORRECTION: Francis Antonie’s surname was spelt incorrectly. We apologise for the error.