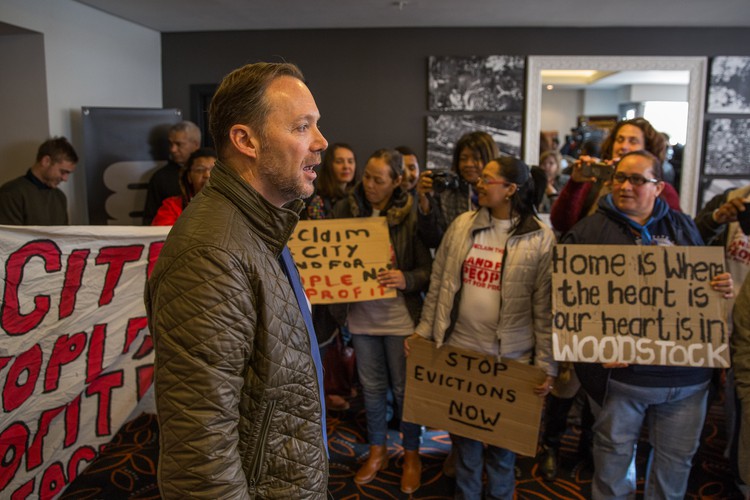

Mayoral Committee Member for Transport & Urban Development Brett Herron speaks to supporters of Reclaim the City during the 4th annual Affordable Housing Africa conference at the African Pride Hotel in Cape Town. Archive photo: Ashraf Hendricks

4 October 2017

The City of Cape Town has announced 13 new sites near the city centre that will be used to develop housing for low-income families. It has also announced that it will no longer develop new houses at Wolwerivier, a bleak new township far from the city centre. GroundUp interviewed Councillor Brett Herron, the Mayoral Committee member responsible for this change in approach.

GroundUp: The City of Cape Town, you said last month, has made a “180-degree change” in its approach to affordable housing. What is different?

Herron: Since 1994, like most other local governments in South Africa, Cape Town focused on delivering the maximum possible number of housing opportunities. This usually meant building RDP settlements where it was easiest to do so: large, cheap pieces of land on the outskirts of the city. While important, this did not address the spatial legacy of apartheid, and actually perpetuated exclusion. The shift is that we’re starting to consider the location of what we’re providing and cater for people overlooked by previous housing policies.

GroundUp: What drove this shift?

Herron: We’ve spoken about the legacy of apartheid planning for a long time, and made commitments to address it, but those commitments have fallen short in pursuit of high numbers of low-cost housing. But where development takes place, and what development takes place, needs to change if we’re to have a more equitable, efficient city. After the 2016 local elections Mayor De Lille pledged to tackle Cape Town’s apartheid spatial legacy, and we’ve taken a number of steps to do so since then, notably adopting the Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) Strategic Framework and forming the Transport and Urban Development Authority (TDA), the institution driving this new process.

GroundUp: Did pressure from activist groups like Reclaim the City speed things up?

Herron: We had already begun moving in this direction, but we must give them credit for introducing public debate around affordable housing in Cape Town and raising awareness about the issue.

GroundUp: Why has it taken so long for the City to take action on well-located affordable housing?

Herron: That’s hard to answer. I’m not sure. The parcels of land that we’ve just released are City owned, and always were. It wasn’t a difficult process. I think the focus was just on providing high numbers on the outskirts, like I’ve said.

GroundUp: What are the biggest obstacles facing the initiative?

Herron: We’ve put out a prospectus and call for proposals. It could fail spectacularly if there’s no response from developers and social housing partners. We’ll have to wait and see.

GroundUp: Is the City relying on national or provincial government for support?

Herron: One of our sites, the Woodstock Hospital, belongs to the Western Cape government, and they’ve made public commitment to transfer it to us. The social housing component of each development will rely on funding from the national Social Housing Regulatory Authority. Other than that we’ve been able to do this more or less alone.

GroundUp: There are much bigger parcels of underdeveloped land in Cape Town, for example Culemborg and the government parking yard on Buitenkant Street. Can the City access sites like these for affordable housing?

Herron: Culemborg is owned by TransNet. There are a number of really well-located parcels of land in the hands of national government, for example Wingfield in Kensington. But although we’ve repeatedly requested transfers to include these sites in our housing plans we don’t seem to have enough influence to make it happen. Our repeated requests have been ignored.

GroundUp: But Province owns the Buitenkant yard. Does the City ask Province for land too?

Herron: Province has already supported us by providing the Woodstock Hospital site. As we progress this project we would like to approach them for additional land.

GroundUp: What about District Six?

Herron: District Six is a restitution project to allow families removed under the Group Areas Act to return. It’s being driven by the national Department of Land Affairs and Rural Development. Our role there, as local government, is purely supportive, so there’s not much we can do to influence the process. We’re very frustrated with the slow pace.

GroundUp: By not disposing of its land at market prices, and rather making it available for affordable housing, is the City forfeiting much-needed cash?

Herron: We’re identifying core pieces of land where we’re prepared to forego some of the market value in pursuit of spatial transformation.

GroundUp: Is that a difficult trade-off?

Herron: Sale of city assets, like land, goes towards ensuring that we have adequate budget for providing services. But economic sustainability is not only about the City’s coffers — we also have to consider the welfare of Cape Town’s citizens. And part of that is addressing the spatial legacy of apartheid, because the current pattern penalises poor, mostly black people living on the outskirts of the city, where apartheid placed them and where democratic governments have continued to place them.

GroundUp: You’ve also announced plans for transitional housing in the city, providing spaces for people evicted from their homes. How will these be allocated?

Herron: At the moment we have two transitional housing sites, in Salt River and Woodstock. Initially they will house people currently living in Pine Road and at the Salt River market, where we plan to develop affordable housing. When we’re finished the transitional housing facilities will remain for other families facing emergency situations.

GroundUp: What opportunities are there for people currently in emergency housing elsewhere, for example Wolwerivier and Blikkiesdorp?

Herron: We’ve set aside our plans to build permanent housing at Wolwerivier, and people will transition out as soon as housing opportunities become available. Blikkiesdorp will be closed down by the end of this term of office, in 2021 — we’re building formal housing for those families at a site in Symphony Way.

GroundUp: Is the City doing anything to curb the market forces that are currently displacing people from places like Woodstock? In particular is the City doing anything about short-term rentals (principally via AirBnb) that drive up prices? If the City is providing affordable housing but people are still getting cycled out of their homes this initiative might prove difficult to sustain.

Herron: A large number of AirBnb rentals in Cape Town are illegal. It is not permitted to rent out entire homes or apartments on a short-term basis.

GroundUp: But is there any enforcement?

Herron: We’ve received a number of complaints but I don’t know the outcome of those. The Mayor’s office also has a policy unit currently researching short-term rentals in Cape Town.

GroundUp: What about requiring developers to include affordable housing in their proposals?

Herron: That’s one way we can intervene in the market: by setting new regulations for awarding development rights. This is termed inclusionary housing policy, where developers contribute to affordable housing, often in exchange for additional rights. We’re currently drafting an inclusionary housing policy framework and I’ve begun a dialogue with developers about how we can go about this. It’s very likely that we’ll have inclusionary housing in Cape Town in the future.

GroundUp: Will Cape Town’s new affordable housing developments have to compete for the same building rights — water, sewage, parking — as private applications?

Herron: Some of our sites have all the necessary rights already, but several will need to be rezoned. We’re planning to look at the planning by-law to assist our housing programs, because currently they need to go through the same laborious steps as any private development, which slows everything down.

GroundUp: What’s happening with Tafelberg now? Many arguments against developing the site (owned by Province, not the City) stated that it was too small to be viable, but several of the sites you’ve just released for affordable housing are considerably smaller.

Herron: We’ve put out our sites speculatively but we believe that they’re viable. I don’t know what this means for Tafelberg.

GroundUp: Your current project targets households earning between R3,500 — R15,000 per month. Are there any plans to provide well-located social housing for people who earn less than that, for example pensioners?

Herron: If we’re going to fully address spatial transformation we have to do it across the entire spectrum. The most frequent questions since announcing our plan have come from pensioners wanting to know how they’ll be included. There are smaller sites scattered across the city that aren’t suitable for dense housing developments, and we’re looking at in-filling these with homes for people beneath the R3,500 bracket. Hopefully we’ll begin exploring this process properly early in 2018.

GroundUp: Your call for proposals states that there will be public participation and voting on each site. What will this look like?

Herron: We’re looking to be as inclusive as possible and build partnerships. The idea is to try and mould the outcome in a collaborative way. We’re not debating if the projects should happen, or where they should happen. That’s been decided already, and we need to move forward.