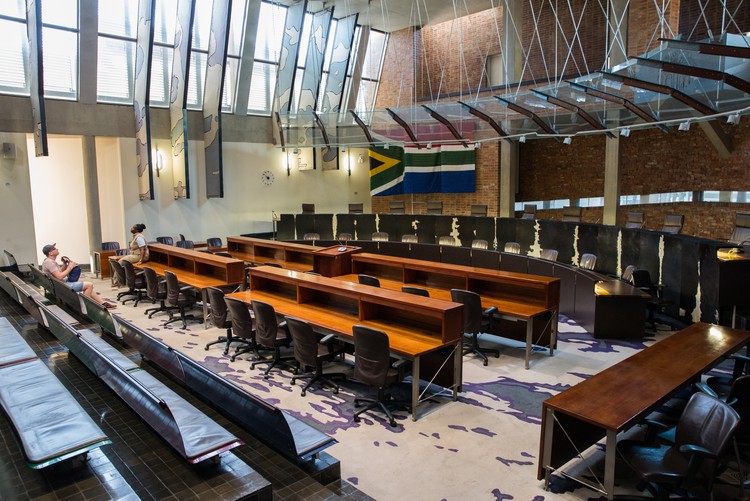

The Constitutional Court has ruled in favour of the majoritarian principle in labour law. Archive photo: Ashraf Hendricks

27 January 2020

When a union negotiates a retrenchment agreement with an employer, should this be binding on employees who are not members of the union? The Constitutional Court ruled on this last week.

The court found that in some circumstances the answer is yes. An employer can finalise a retrenchment agreement with a majority union – and the outcome will bind minority unions, even when their members have not been consulted.

One of the objectives of the 1995 Labour Relations Act (LRA) was to guarantee the freedom of employees to form and join trade unions and to strike, and the rights of trade unions to bargain collectively with employers and employers’ organisations. In line with international accepted mechanisms, the majoritarian path was chosen to realise these objectives. That means giving preferential or even exclusive bargaining rights to trade unions that represent the majority of employees.

Minority unions have recently challenged this model in the courts. The most recent of these challenges was decided by the Constitutional Court last week by the narrowest of margins.

In August 2015, mining company Royal Bafokeng Platinum Limited entered into consultations with the majority union at the mine, National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), and United Association of South Africa Union (UASA), one of the two minority unions (the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union or AMCU was the other), about retrenchments. A retrenchment agreement was signed on 18 September 2015. The agreement was extended to all employees, whether they were members of NUM or UASA or not, as is permitted by section 23 of the LRA, and provided that all employees to be retrenched waived their rights to challenge the lawfulness or fairness of the retrenchments. AMCU was never included in these consultations.

With some of the retrenched employees, AMCU approached the Court to challenge the constitutionality of sections 23 and 189(1) of the LRA.

The court was unanimous that section 23(1)(d) of the LRA, which allows for collective agreements to be extended to employees who are not members of the majority union was not inconsistent with the right to fair labour practices, as AMCU had argued. Even where the extension of the collective agreement related to retrenchment, the limitation was justified, the judges ruled, considering the benefits of majoritarianism in encouraging the democratisation of the workplace and curbing the proliferation of trade unions in that space.

The interpretation of section189(1) on the facts was more complicated. This section sets out the requirements for consultation when an employer contemplates retrenchments. It requires the employer to

The question raised was whether this section allows the employer, when a collective agreement is signed on retrenchment, not to consult at all with employees who belong to a union that is not party to the agreement. Is it fair to be retrenched without having any say about it, either in person or through the representative union of your choice?

In a five-to-four split judgement, the Constitutional Court ruled that it is indeed a fair labour practice. Judge Johan Froneman, writing for the majority, emphasised that this section has consistently been interpreted in this way by South African Courts “for at least twenty years”. If one accepts that the majoritarian principle on which section 189 is based is constitutional, he continued, one must accept that the consultation requirements set out in section 189 are consistent with that principle and the Constitution. To contemplate parallel and individual consultations, is to undermine the very point of collective bargaining, he wrote.

Acting Judge Aubrey Ledwaba, writing for the minority, found that employees facing retrenchment do retain a right to be consulted. In so far as section 189 does not require individual consultation with employees who stand to be retrenched, it limits the right to fair labour practice. Judge Chris Jafta, who wrote a separate judgment in support of the minority, argued that the facts of this case show that section 189(1) not only enables discrimination, but infringes on the right to free association. Members of AMCU were denied the protections afforded the members of NUM and UASA, he wrote, and therefore were denied the equal protection and benefit of the law solely for the reason that they chose to join AMCU. As such, section 189(1) is indeed unconstitutional, he found.

The majority rejected this interpretation and set out why the protection of the majoritarian principle protects employees. Offering individual consultation “can only be near-futile” , wrote Judge Froneman. “An individual employee, or even a group of individual employees, has or have scant bargaining clout, particularly where the employer is preoccupied with processing dismissal for operational requirements. A majority union, by contrast, wields coercive power, by immediate or future threat of industrial action. It is this power that may sway an employer to agree to benefits on retrenchment, or better yet, fewer or no dismissals.”