Ndifuna Ukwazi’s demarcation of the inner city and surrounds where there is a need to use publicly owned land for affordable housing.

6 September 2016

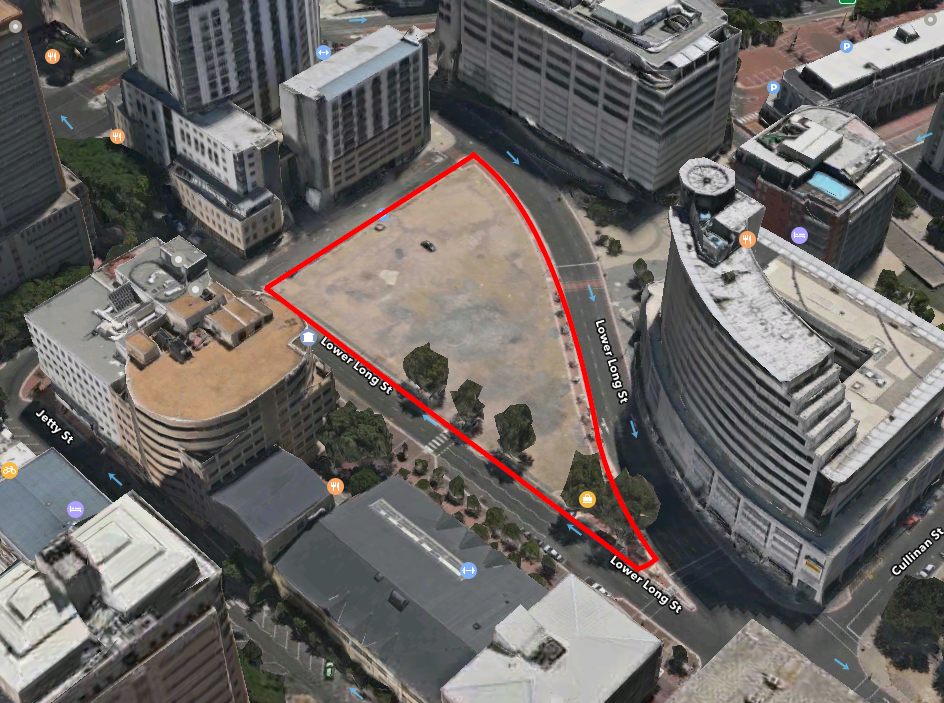

On Wednesday this week, the City of Cape Town will dispose of a prime piece of inner city land. Known as Site B and located on Lower Long Street on the Foreshore, it is currently a four hectare, open air parking lot surrounded by towering buildings. It is clearly under utilised as a public asset and selling such a property to the highest bidder is unacceptable.

Cape Town suffers from a dysfunctional urban phenomenon known as ‘inverse densification’. A largely poor and working class black majority live on the urban periphery, in very densely populated settlements, far from jobs, and with poor access to amenities and services.

Well-located central areas, most of which were previously designated “whites only” areas, are characterised by low densities coupled with an acute shortage of affordable housing options, despite excellent access to amenities, services and employment opportunities.

Inverse densification did not happen accidentally. Some 60,000 people were forcefully removed from District 6 alone. This, according to the 2011 census, is almost exactly the number of the current residents of Cape Town’s two inner city wards combined, comprising the CBD, Bo-Kaap, Gardens, Tamboerskloof, Oranjezicht, Woodstock, Salt River, Observatory, Mowbray and Rosebank.

Schedule 6 of the Constitution, National Unity and Reconciliation, challenges our society to build a bridge between a history characterised by division, suffering and injustice, and a future founded on the recognition of human rights, democracy and development opportunities for all South Africans. This should be at the centre of any decision which will materially shape the future of our city.

Cape Town Mayor Patricia de Lille says that the disposal of Site B is in line with efforts to create an “opportunity city” by driving economic development with the release of immovable property not required for municipal purposes, in order to stimulate economic activity, economic investment and job creation. This rationale must be challenged. The onus is on the City of Cape Town to explain why prime public land is not required for municipal purposes in the midst of housing, segregation and restitution crises.

This land logic exposes a limited understanding of the value of land in securing broad-based growth. We need to move beyond simplistic trickle-down economics. Well-located affordable housing, bringing workers closer to their place of work, is not only about welfare, it is a necessary public investment for the long term economic sustainability of Cape Town.

The 2016 State of the Central City Report estimates conservatively that there is R8 billion of property development planned for the CBD over the next five years. Furthermore, the nominal value of property in the CBD, which is only 1.6 km², shot up 26% between 2005/6 and 2013/14, from R6.127 billion to R23.725 billion. Today, according to a Frank Knight report, at triple inflation, the growth of Cape Town’s property market is the third fastest in the world – behind Vancouver and Shanghai. Can the City justify stripping public assets for short term cash injections to drive economic growth in the CBD? Why haven’t we used this tremendous growth to secure affordable housing stock in the area - something done by ‘world class’ cities the world over?

Given our apartheid history and Cape Town’s oft touted mantle of ‘good governance’, the City should be a global leader in fostering urban inclusion. Yet in 22 years of democratic rule, not a single subsidised rental housing unit has been created in the inner-city.

The affordability crisis also means eviction for many poor tenant families in traditionally working class suburbs like Salt River and Woodstock. Black working class and poor people are forcibly relocated to the urban periphery and camps like Blikkiesdorp and Wolwerivier.

Instead of mitigating against the markets’ exclusionary tendencies, the City is aggravating the situation by selling off parcels of prime public land.

The most obvious way to restructure Cape Town to bring more people back into the city and surrounds, is to leverage publicly owned land to create affordable housing close to economic and social opportunity. This requires government to release land below market value to meet its socio-economic obligations. Not only is this possible, but it is mandated by the existing legislative framework and constitutional framework for restitution as broadly defined by the principle of spatial justice.

As with many challenges South Africa faces, it is not policy or legislation that is missing, but political will. Instead of acknowledging the social value of land the City fixates on its commercial value only. State owned land is not a current account. It is a scarce and finite asset and is immensely valuable from a social, environmental and cultural view as well.

The City regularly uses the shortage of well-located land or the impossible expense of obtaining such land as the excuse for failing to provide affordable housing in well-located areas - yet at the same time it’s selling that which it has.

That some senior politicians in Cape Town, Deputy Mayor Ian Neilson and Councillor Benedicta van Minnen for example, think that the desirability of inner-city affordable housing is still up for debate is alarming. But it isn’t surprising, given that Neilson argues that Langa is part of the “inner city” and Van Minnen claims that the human dumping ground of Wolwerivier is in line with spatial planning objectives because it’s in a “future growth corridor”.

Neilson claims that the Reclaim the City campaign demand for inner city affordable housing is “oversimplified and ill informed”. But these campaign demands, for the protection and promotion of well-located affordable housing with a current focus on the inner-city and surrounds, happen to be grounded in the policy and legislation which should guide the City’s implementation of planning and housing strategies.

Cape Town’s urban exclusion crises are a result of “death by a thousand cuts”, when land desperately needed for housing and integration is sold off on an ad-hoc basis.

Site B was once part of the Foreshore Coal Power Station, which was parcelled up into eight pieces of land after it was decommissioned. So far, seven of these eight pieces of land have gone to prime office space: Investec, ENS and Protea Wharf buildings; luxury apartments at the Icon or five star hotel space for the Southern Sun Cullinan Hotel. Add to this, the sale in 2011 of a portion of land now occupied by the Portside building, Virgin Active next door to SARS in 2014 and the imminent disposal of Site B, and that is ten sales within a 500 metre radius.

None of these disposals have contributed to affordable housing development either on-site or in the vicinity. Although Portside was linked to the provision of housing, albeit in Khayelitsha, some eight years down the line this contribution has yet to materialise.

There are many more public land disposals in the inner-city and surrounds that have gone ahead or are being lined up - whether for long term lease or outright alienation. At the controversial Western Cape Property Development Forum in 2015 Mayor Patricia de Lille announced that, in addition to Site B, another twelve high value properties would be released to the market. These properties include land in Century City, Foreshore, CBD, Green Point, Clifton and the Strand Street Quarry in Bo-Kaap.

This must be considered alongside the four substantial properties that Provincial government aims to dispose of through its regeneration programme - Tafelberg in Sea Point, Helen Bowden Nurses Home in Green Point, Alfred Street Complex and Topyard in the CBD. If we turn the clock further back, we see that of the 150 hectares of land that once made up District 6, only 40 hectares of publicly owned vacant land remain.

State owned land which has been sold off in the vicinity of Site B (in red) and proposed for sale (in orange) by the Provincial and City government

State owned land which has been sold off in the vicinity of Site B (in red) and proposed for sale (in orange) by the Provincial and City governmentThis trend of asset-stripping has powerful allies. Private developers have become increasingly cosy with high-ranking politicians and officials. The scandal around Gary Fisher, who wears two caps as public official in provincial government and real estate mogul, and his substantial personal interests around the disposal of the Tafelberg site, is one such example. That developers and property investors have increasing influence in the shaping of our city should be a cause for concern. Readers should remember that whenever you have shortages, you have big corruption risks. One has to ask, who are the gatekeepers of these resources, and how are they being allotted?

Meanwhile, in the face of all of this there is no holistic plan linking government owned land to its socio-economic objectives. Soon, there will be no land left to create the Cape Town our Constitution demands.

Correction: An earlier version of the article stated “Cape Town’s property market is the third fastest in the world – behind Toronto and Shanghai”. Toronto was an error and has been replaced with Vancouver.

Views expressed are not necessarily GroundUp’s.