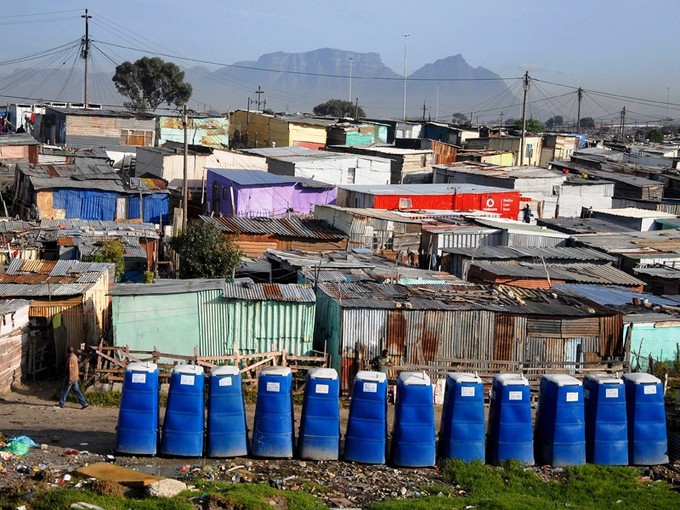

Portable toilets in Khayelitsha. Photo: Masixole Feni

4 July 2016

The Social Justice Coalition (SJC) has taken the City of Cape Town to the High Court and the Equality Court for failing to respect “the right of access to sanitation of poor, black and marginalised residents of informal settlements”.

The SJC wants the City to present to court, within three months, the measures it will take to implement permanent sanitation facilities in informal settlements that are not temporary settlement areas.

Last week, the SJC filed affidavits from five women living in informal settlements in Khayelitsha. There is an additional affidavit filed by Conrad Barberton, director of Cornerstone Economic Research, a company hired in January to develop a Sanitation Costing Model for the City of Cape Town.

The women’s affidavits describe the humiliation that goes with lack of proper sanitation, the illnesses their families regularly suffer, and their fears for the safety of their children, especially at night.

The SJC alleges that the City uses temporary, emergency sanitation solutions to address issues in informal settlements that were established decades ago.

“It’s sad that in 22 years of democracy, every administration, regardless of political party, has failed the people of Khayelitsha,” said Zackie Achmat of Ndifuna Ukwazi’s law centre at an SJC press conference this morning.

“There is a street light on the street outside my home, but it has never worked since it was installed in 2013. I try not to go outside in the evening because it is very dark outside at night, and there are gangsters that walk around at night,” she states in her affidavit.

“I am afraid to go to the communal toilets or the bush alone at night; so I wake one of my older children to walk with me. Before I can go to the toilet, I must first find a neighbour who is home and can give me a key to the toilet. This can take a long time, because not a lot of people go to the toilet at night.

“If I cannot find a key, I ask someone to accompany me to the bush. If there is no one to accompany me, then I have to wait until the morning before I can go to the toilet.”

Lindela Bebi has been using the same Portable Flush Toilet (PFT) since 2002. The lid, seat, and brackets to attach it to the ground are broken.

“When the children and I try to sit down, the toilet shifts around and the contents leak and spill all over the ground. The shelter I built to store the PFT is filled with maggots, flies and mosquitoes because of the smell and waste from the leaking PFT,” she says in her testimony.

“When I first received a portable flush toilet in 2002, I was told that these types of toilets would be temporary and that I would only have to use it for three months. I have been using these portable flush toilets for almost 14 years now.”

Nosiphelele Msesiwe moved to Enkanini in 2006, where she and others used a bush as a toilet. A neighbour offered a pit toilet to share with five other families shortly afterwards. She received a PFT in 2008, which she did not like.

“I had to keep it in the house and had to use it in front of my young son. I felt humiliated because of the lack of privacy. I was extremely uncomfortable with having to bare myself in front of him on a daily basis.”

In 2011, chemical toilets were delivered to people a ten-minute walk from Msesiwe, and she began using one. The chemical toilet is shared by many people and only cleaned twice a week. Without the cleaning chemicals, residents cannot clean it themselves. It attracts flies due to poor ventilation.

In 2015, the flush toilets at Chris Hani station, a 30-minute walk from her home, were demolished. She was told it was to build new toilets, but they have not yet been replaced.

Nobathembu Seplani uses a PFT because she is denied access to flush toilets 20 metres from her home. The people living closest to the toilets do not like to share.

“To use these toilets is degrading, unsafe, and demeaning. It violates my right to human dignity, my right to safety and security of my environment, my rights to privacy and my right to be treated as an equal citizen like other South Africans.”

The City told her that her area is a floodplain, so flush toilets cannot be installed.

Nolizwe Maneli has been using the same PFT since 2005.

“Previously we would relieve ourselves in an open field that is located next to the N2 highway. We would go about our business in full view of passing traffic.”

“I often hear of stories of people being shot and woman being raped while trying to use the toilet at night. I fear for the safety of my and my children’s lives every time we have to use the toilet.”

She hates the PFT. “In some ways, it is better to use the bush or the open space next to the N2. I feel like I do not belong in this country when I use this toilet.”

In his affidavit, Barberton broke down the short- and long-term cost of providing different types of toilets to people living in informal settlements. He found that in the short term, PFTs and chemical toilets may seem the cheapest option. Installing ablution blocks (public toilets) are the most expensive.

However, over a longer period of time, the cost of chemical toilets and PFTs drastically increases, making them the most expensive sanitation option. The provision of individual flush toilets in every home becomes the most cost-effective solution in the medium and long term. Some settlements in Khayelitsha would need houses to be moved to decrease the density of homes and allow the work to be done.

Another constraint considered was the flood plain in Khayelitsha, which increases the installation costs of individual flush toilets by around 2%.

Even with the flood plain and blocking constraints, Barberton found that installing individual flush toilets in every home was by far the most cost-effective use of the City’s money.He recommended that the City should implement individual full flush toilets as soon as possible, aiming to overcome the minimum ratio of one toilet for every five households within the next two years.

Simon Maytham, media liaison officer for the City, said the City was consulting its lawyers and would comment later today. GroundUp will publish the comment when it is received.