9 April 2024

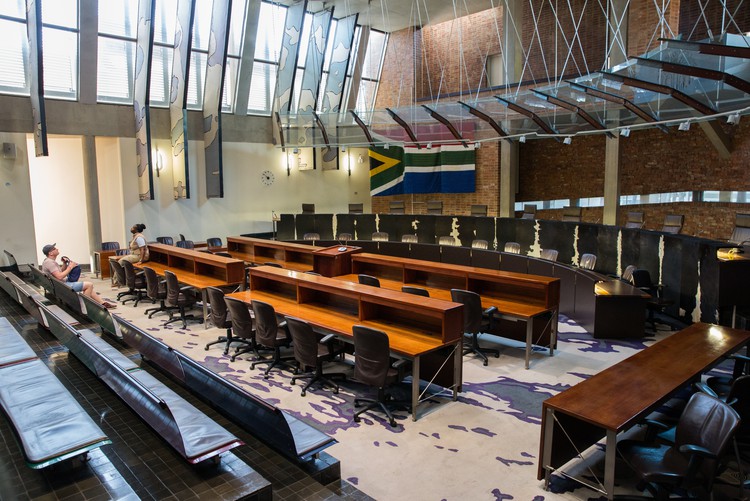

The Constitutional Court has yet to hand down any judgments this year. Archive photo: Ashraf Hendricks

We are now into the second quarter of 2024, and the Constitutional Court has yet to hand down any judgments.

From a survey of the law reports, the court’s late start is unprecedented. Usually, within the first two months of the year, the business of the court in deciding consequential matters is well underway. By this time last year, the court delivered ten judgments. The year before, at least 13.

In at least 15 matters, judgment has been pending since last year. Eight of those have been reserved for six months or longer. In other words, there are many litigants that have been anxiously waiting for the Court’s decision for months, and the backlog is growing.

For court watchers, this seeming paralysis in activity is as baffling as it is worrying. Concerns over the Court’s efficiency have been mounting for some time. A recent UCT study has shown that between 2010 and 2021, the time the court took to hand down judgment effectively doubled. This trend tracked a parallel rise in the number of applications made to the court over that period.

Judges of the court have admitted that the courts case load is placing its systems under strain. And, to his credit, Chief Justice Raymond Zondo has openly acknowledged the problem. But plans to address it have not inspired confidence. The court has tweaked its internal procedures for deciding new applications, but this does not seem to have borne fruit (though this is difficult to assess fully, as information on the time taken to decide applications is not easily accessible). A recent scheme to co-opt retired judges in the processing of new cases was also recently abandoned, following criticism of the proposal.

Another measure has been proposed that has received less public attention. In a recent judgment the Chief Justice indicated that in some cases, considering the court’s workload challenges, the judges may not write a judgment following a hearing. Instead, a matter may be dismissed through a short “statement” of reasons. While the court regularly dismisses applications in chambers without a published judgment, it would be a novelty for this to be done in cases that have been set down for a full hearing. After all, if a matter is considered important enough to be placed on the court’s roll, one would assume it at least deserves a reasoned opinion.

More generally, we should be cautious about how and when such expedited processes are used. As Steven Vladeck shows in The Shadow Docket, the use of expedited decision-making procedures by the US Supreme Court has led to worrying trends where consequential matters are decided through dubious orders, without a hearing and without full reasons (in some cases, the orders are not even signed by the judges).

While we should not rush to draw uncritical parallels with the US system, one recent case merits our concern.

In Rivonia Circle NPC v President of South Africa, the applicants brought an urgent application challenging the constitutionality of the legislated signature requirements for unrepresented political parties. The case is obviously important, with high stakes for the country’s upcoming elections. Surprisingly, the court elected to dismiss the matter without holding a hearing, and without issuing a full judgment. Instead, an order was issued from chambers (some two months after the application was filed).

Reasons for the dismissal were set out in a short paragraph. Even more, there was a dissent – possibly a first for an order issued in chambers. The order recorded that Acting Justice David Bilchitz was of the view that “because of the very important fundamental rights implicated in this case”, the matter should have been enrolled, heard and adjudicated.

Our issue here is not with the outcome in the case, but the process by which the court went about deciding it; even if motivated by the best of intentions. Former Justice Kate O’Regan once famously described the role of the apex Court as a “forum for public debate” and that this role “carries with it a conception of democracy, which requires the exercise of power to be accountable”. This democracy and accountability-reinforcing role of the court is diminished when debate and disagreement are sacrificed at the altar of efficiency. Even more so when the court has yet to demonstrate any gains in that direction.

Structural changes are needed, both to ensure the efficient administration of justice, and to uphold the court’s role as a forum for reason. These twin goals should not be viewed as trade-offs; they are complementary. Together they can enhance the legitimacy of the court and deepen the quality of our democracy.

While the Chief Justice must undoubtedly take the lead in driving necessary reforms, all members of the court will need to play a role. In this context, one hopes that when the Judicial Service Commission meets this week, they will not only take into account the track record of judicial candidates for the apex bench, but also that of the court itself.

Nurina Ally is director of the Centre for Law & Society and senior lecturer in the Department of Public Law, University of Cape Town. Mbekezeli Benjamin is research and advocacy officer at Judges Matter, a project of the Democratic Governance and Rights Unit at UCT Law Faculty that monitors the judiciary in South Africa.