1 February 2023

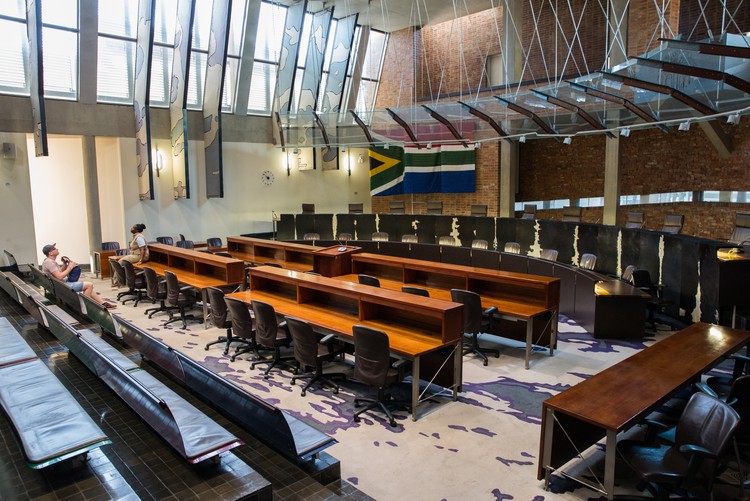

Online record-keeping at the Constitutional Court has been neglected of late, says the writer. Archive photo: Ashraf Hendricks

Nurina Ally is Senior Lecturer in the Department of Public Law at the University of Cape Town. She writes in her personal capacity. Views expressed are not necessarily those of GroundUp.

The records on the Constitutional Court website are a crucial resource for lawyers, academics, journalists and the public. But in recent years record-keeping has been neglected and key documents are sometimes missing.

Reliable, up-to-date information on the Constitutional Court’s website is all-important to ensuring transparency, participation, and accountability in the Court’s work.

When first established, the Court appeared to be leading the way in effective online record-keeping. Justice Dikgang Moseneke was so in awe of the Court’s website when he first joined the Court, he described it as a “marvel”. But the zeal for innovation has seemed to wane. Worse, there are signs of neglect.

Until recently, pleadings in a case would be uploaded to the Court’s website soon after being filed. Interested observers could read the documents well before the hearing date. This made it possible to identify hot-button issues in the forthcoming term and to analyse submissions ahead of hearings. Such access is of obvious interest and benefit to litigators, academics, journalists and court commentators. Records of this type are also useful to members of the public who have an interest in attending hearings and following the work of the country’s highest court.

There has, however, been an unexplained retreat from the Court’s established practice. Submissions in forthcoming cases are now made available only a few days before the matter is heard (if then). This makes it difficult to preview the issues that the Court is set to determine. As I write, the Court’s first term for 2023 is due to begin in just a few days. Yet submissions in the first case to be heard were only uploaded on Monday. There is no information available on any other matters on the court roll.

To be fair, the Court does issue a summary of a case the day before it is due to be heard. These are also posted on the Court’s Twitter account. This is welcome, but these case-by-case alerts do not afford court watchers an opportunity to engage with the issues that the Court has listed in its upcoming term.

Making matters worse, the Court’s ‘case flow’ records have been stagnant since June 2022. This means that the status of new applications filed before the Court has not been publicly updated in seven months. The most recent report on the status of reserved judgments across the judiciary is over a year old. As a colleague and I have observed in a recent study, the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the Court’s case flow records leaves much to be desired. Yet these records are the public’s only glimpse into the bulk of the Court’s work (as most applications are decided in chambers, with a relatively small proportion set down for hearing). When these records are not provided, or left woefully outdated, the public’s access to the Court’s decisions is inadequate.

In addition to records not being updated timeously, there are gaps in the online case filings. Whereas obvious omissions used to be rare, it is no longer surprising if the record of a case is incomplete. This is alarming, as the Court’s website serves as a digital archive of all the cases heard by the Court. If the original filings are destroyed, or go missing, the case documents may be lost altogether.

Worryingly, the delays and gaps in its online records mirror what appears to be a general decline in the Court’s case management systems. In recent years, there have been several disquieting reports of applications and submissions filed before Court going missing. Last year, for example, justices were left scrambling in at least two cases where they had not been supplied with all relevant submissions. In one case, the Court had to “rescind” its judgment shortly after delivery. In another, the matter was delayed and ultimately postponed. Embarrassing and costly, such incidents threaten to undermine public confidence in the country’s highest court.

It is encouraging that the Court’s new leadership (Chief Justice Raymond Zondo and Deputy Chief Justice Mandisa Maya) have recognised the need to improve aspects of its functioning. Ensuring that the Court’s online records are accurate and regularly updated is a modest, but important, intervention that will advance the constitutionally-mandated values of responsiveness, openness and accountability. These are, after all, values that the Court has a duty to uphold.