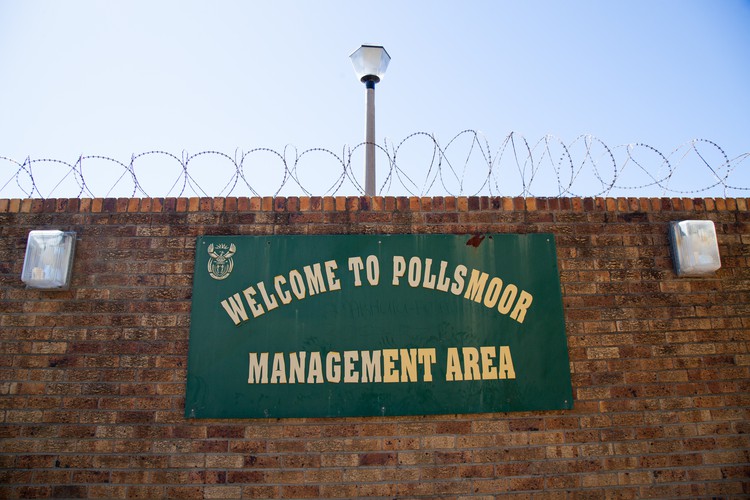

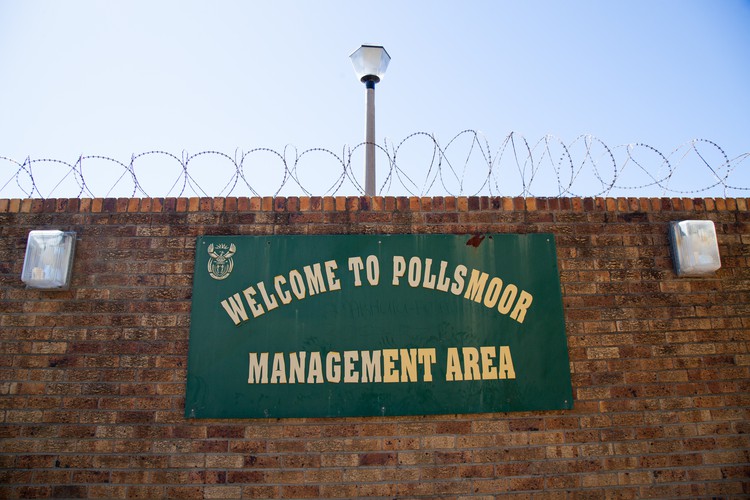

Inmates may have the best ideas about how to prevent the spread of the coronavirus in prisons, writes Peter Christians. Archive photo: Ashraf Hendricks

21 April 2020

In an ideal world, we would prevent Covid-19 from entering prisons. But we do not live in an ideal world. Prison wardens travel from their homes and neighbourhoods by various means of transport to the workplace every day, and any one of them could be a carrier of the virus. Not to mention the influx into the prisons of people still being arrested every day for minor offences and who cannot make bail or pay fines. What happens in a prison if the virus slips through undetected?

I was incarcerated for six years at Pollsmoor Prison and now work there facilitating conflict resolution workshops for inmates with the Alternatives to Violence Project. So I know how difficult hygiene practices and social distancing are for inmates, even under “normal” circumstances.

Picture 70 to 100 people in an 8x24m2 room or 40 people in an 8x12m2 room, with three of the walls lined with double or triple bunk beds. Without enough beds to go around, priority goes to gang members, while others push beds together and share. Up to ten men can sleep across four beds. In my experience, prison is not a place where men get all touchy and smoochy. In fact, the personal space of a man is to be respected, but that personal space is limited to about 45cm.

Surfaces such as beds, walls and lockers are used for various purposes: beds are also used as couches; weight-lifting equipment or used as partitioning between gangs and ranks; and walls and windows are used not only as washing lines, but also as coveted balconies on which to catch rays of sun and to communicate with brothers and associates in neighbouring cells.

The lockers also double as tables during mealtimes and desktops for writing, or simply to gather around to play a game of dominoes. These surfaces are being touched repeatedly by many people, who have nothing else in their space to touch. Bathrooms in the big dormitory rooms have three basins, three showers and three toilets. In the smaller dormitories, there is only one hand basin, one shower and one toilet. Each room is kept clean by the occupants themselves, and they organise their own teams and schedules.

Mops and brooms do get issued, but in a tight living space, conflict and violence are inevitable; items rarely last a full week before they break on something or somebody. More often than not, you have to clean surfaces with pieces of torn cloth, on your hands and knees. As a result, skin irritations, rashes and fungus-related skin ailments are common.

Personal hygiene necessities are distributed by the Department of Correctional Services, but they are hardly enough for every inmate. Many depend on visits from their families or loved ones to supplement the little they get from the Department, including essentials like toiletries, underwear, towels and bedding. Now that the government has banned prison visits, the washing and sanitising of hands, bodies and surfaces in prison is further compromised.

How do incarcerated persons implement social distancing in these one-room dormitories? Inmates are already in a “lockdown” state in which movement is restricted to the four walls of these rooms. When I was in prison, we used to pace or jog up and down the cells or during our one-hour-a-day access to the courtyard. By 2pm, we were back in lockdown for the wardens to change from day to night shift.

Wardens work in two shifts: a day shift, which has most hands-on-deck, and a skeletal night shift to check up on doors, gates, windows and safety issues. For social distancing to be properly applied, dormitories will have to hold fewer people and access to courtyard and other spaces extended. As of now, the danger is within these overcrowded rooms and cells.

Smoking cigarettes is another danger. One cigarette is never smoked by fewer than three people at a time and even though government regulations prohibit smoking, wardens know the complications it would cause to refuse inmates tobacco and therefore they are lenient. But we know that the government regulation will have to be adhered to in order to prevent Covid-19 from spreading like wildfire. I don’t want to imagine the impact this will have on the high level of conflict amongst inmates, because tobacco is already a commodity for which some inmates sell their food, toiletries, clothes or even their bodies. One can imagine how people dependent on tobacco could be exploited in such a scenario.

Prison under “normal” circumstances already has an enormous psychological impact on the human being and it can lead to high levels of volatility and conflict. Many inmates will not be able to withstand the mental and psychological strain during this time. Will counselling and conflict resolution resources be made available, and if so to what extent?

Taking away visits from family or loved ones, which are vital for the mental health of prisoners, is a recipe for disaster. Those with family members need contact for encouragement and moral support. Is the government ensuring this vital contact with loved ones continues? Are steps being taken (drop off-points) for families to send their loved ones the usual, acceptable, parcels of toiletries and other basic necessities? I would suggest getting volunteers to help with these processes, including the sanitisation of goods, if the Department does not have enough manpower.

As the number of Covid-19 cases in South African prisons increases, I am concerned about what is to come for people inside. There are many practical, psychological and logistic issues to be solved to prevent a Covid-19 catastrophe in prisons.

But this is my main concern: The elderly, immune-compromised and other vulnerable inmates are in grave danger. We need action now, not later.

It is imperative that the Department of Correctional Services and its officials communicate and facilitate whatever measures they decide to put into place with inmates, and with the big players within the Numbers Gang and its members, because once the wardens lock the gates, the Numbers are responsible for how things are done.

Inmates have their own rules, regulations and hierarchy, by which they live and operate. The wardens may manage the politics and government requirements in order to keep prison “doors” open, but the inmates and the “Numbers” are the ones who rule.

But all of us, inmates included, Number or otherwise, need to understand that this virus is bigger than any one of us and that we need to work together to combat this pandemic. Listen to the inmates, they might even have the best ideas on preventing the spread in prison. This is their community at this moment in time, and they also need to look out for each other.

Wardens in turn are responsible for the safety of inmates but going in guns blazing and turning “normal” day-to-day operations upside down will be useless to the greater cause of preventing further infections or fatalities from Covid-19.

We need to reach into the humanity within each of us to conquer this virus.

Those incarcerated are no less human than those outside. Whatever crimes they have committed do not make them unable to make a contribution to society ever again. Whatever crimes they have committed do not make them unlovable to their sisters, brothers, parents or children. We are all human, and every human life matters.