8 June 2020

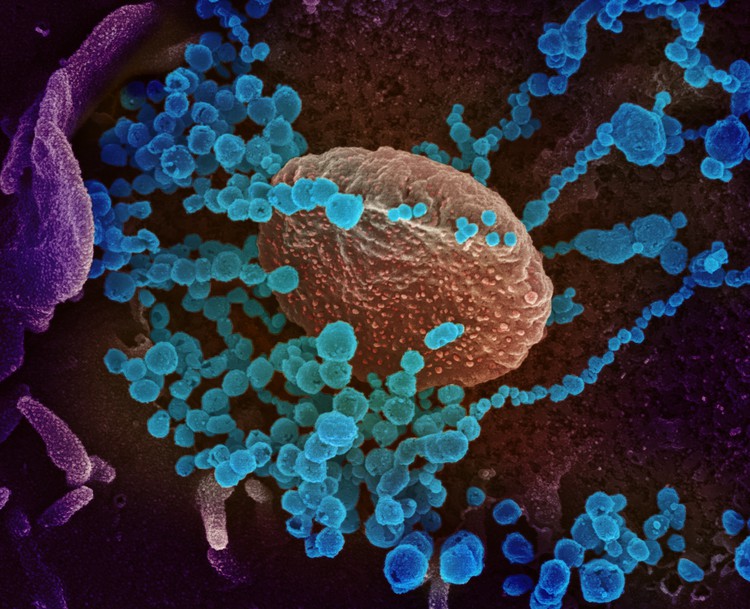

The author criticises the lack of government transparency about the Covid-19 epidemic. (Image of SARS-CoV-2 virions emerging from a cell by the US NIAID, CC BY 2.0)

The response required to address the Covid-19 pandemic in South Africa could reasonably be argued to necessitate the extraordinary step to invoke the Disaster Management Act. After all, in times of crisis even the old Roman republic allowed for the temporary appointment of a dictator.

Such measures are self-evidently risky for democratic governance, as any temporary concentration of power into the hands of the few has the nasty habit of becoming permanent. So when this occurs, countervailing measures are reasonably required to ensure that power remains accountable to society. This avoids any detour into despotism. Central among these is transparency, together with a reasonable preservation of the separation of powers in government. Without transparency society is blinded and the institutions of social accountability thwarted.

It is for this reason that despots throughout time have despised and vehemently opposed transparency. Despotism in all its forms thrives on secrecy. Transparency as a fundamental driver of accountability de-legitimises bad actors and bad purposes. By its very nature it generates direct and indirect consequences of various forms for those in positions of power when they behave badly - but also when they perform well. Society can however only challenge and apply consequences to what they can see.

So when the National Coronavirus Command Council (NCCC), a supposed construct of the Disaster Management Act, decided to make decisions in the dark, refused to make the rationale for major decisions public and centralised all communications about Covid-19, the warning lights came on. The countless hours of mostly aimless and meandering briefings by various politicians reflect only the appearance of transparency – as matters of substance are carefully avoided or fobbed off.

While page after page of poorly formulated regulations poured out of the NCCC, it soon became clear that the crucial steps required to prevent or address the pandemic were not front and centre of any approach. The countries that were successful in containing the outbreak scaled up testing, tracing and quarantining as a substitute policy option to the economically and socially damaging generalised lockdowns. Where this was done successfully there was no need to expand bed capacity as they emphasised prevention over treatment.

The South African government argued that the lockdown was essential to buy time. But for what? Testing and tracing? Increased bed capacity? Both have actually been argued at different stages of lockdown.

During the initial stages of the lockdown government suggested that it would expand testing to 36,000 tests per day with a 24 hour turnaround by the end of April 2020 using the centralised National Health Laboratory Service (NHLS). This would be in addition to private sector testing which has consistently remained at around 7,000 tests per day. So it was implied that we would reach at least 43,000 tests per day by the end of April.

But when NHLS testing fell way below its target as well as the efficiency levels necessary to contain the epidemic, all while new infections continued to rise despite the lockdown, the narrative started to change.

Suddenly the purpose of the lockdown changed to preparing beds for a “coming storm” – arguably an admission of the failure to expand testing and tracing. The failure of the NHLS to expand testing capacity as promised has necessitated a retreat from community-based testing due to the extraordinary turnaround times which exceed seven days.

However, there is no evidence in the form of a coherent database or public report that critical care bed availability has changed materially from March until June. Provision has however been made for more general ward care, using field hospitals, in the public sector – but with most provinces still unprepared. Furthermore, in the entire period from March to May 2020, no framework was completed to access private sector beds for public sector Covid-19 patients. It is however expected that some approach will be finalised during the course of June.

And while public reporting on the testing programme has improved a little, it remains mysteriously weak and incomplete.

The worrying increases in new infections during April, May and into June 2020 raise many questions about the underlying disease trajectories, which are difficult to evaluate using the information made available to the public. To understand the community-based dynamics, it is necessary to examine data at a granular level. Over-aggregation combines communities with diverse characteristics and severely constrains an analyst’s ability to determine localised disease reproduction rates and assess whether interventions are working.

Poor data by date and area for screening, sample collection, test result and contact tracing means we also have no ability to evaluate whether a strategy is working or whether some intervention platform is under-performing.

While it could be argued that some “expert” team is beavering away behind the scenes on our behalf, there is no evidence of this. More importantly there is no logical rationale for keeping the underlying data or any analysis performed away from the public eye.

It is worth quoting the health warning offered by Media Hack for their belated attempt to collate coherent data from the Department of Health into a plausible dashboard:

“Every day we collect data related to the Coronavirus pandemic in South Africa. The data released by the department of health is very limited and irregular. We often have to source and verify the data from multiple sources.”

Of more concern is the fact that the more granular data is available only to researchers who are prepared to sign a Non Disclosure Agreement (NDA), apparently at the behest of the Minister of Health, which limits their ability to disseminate the information further.

By way of contrast, if you want similar data from Kerala in India (by district), Karnataka in India (below district level), or from the government of the United Kingdom (down to lower tier local authority – broadly equivalent to South Africa’s local municipality regions), it is freely available to the public as downloadable data.

A cursory review of these government sites (and there are many more examples) offers both ordinary citizens and researchers good information to evaluate their own risks and understand what their governments are doing. The sites are properly designed, rich in information and useful. Quite simply, they are transparent – and proactively so.

Within the South African public sector only the Western Cape offers information at a level equivalent to that of these other countries. The other South African provinces however merely offer links to a spartan national government site.

The reasons for the failure to provide adequate data to the public can only be guessed at, as no clear rationale comes to mind. As the epidemic worsens in South Africa, the public dissemination of relevant data is an obvious imperative consistent with the principles of a democratic society. Perhaps now is the time to have this discussion publicly.

Views expressed are not necessarily GroundUp’s.