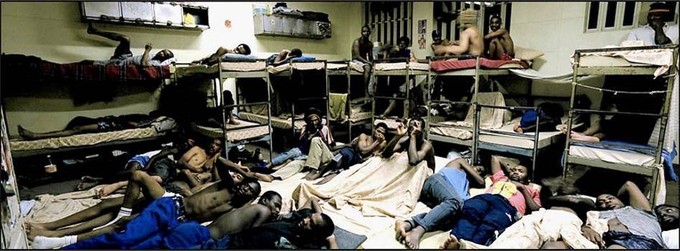

Inmates at Pollsmoor Prison. Photo courtesy of Robin Wood.

20 July 2016

Visitors arrive before 6am, sitting on the wooden benches, bundled up in blankets and beanies, warding off the icy wind. Babies as young as two months sleep soundly, held close to their mothers’ chests. Bags containing food, clothes and blankets are held protectively, to be taken to the visitors’ loved ones inside Pollsmoor Prison’s remand centre for those awaiting trial.

As the minutes tick past 7am, which is the official start for “visiting hours”, the queue begins to get restless as the gates remain firmly closed. An argument breaks out near the front as some visitors appear to have pushed into the queue. Tensions simmer down when the guards come out and begin to hand out numbers to the visitors. It is now around 8:30am and the line of people is snaking into the car park.

The toilets for visitors look dark. A woman exits, says it’s pitch black inside and stinks. “If it’s so badly managed out here, I wonder what it’s like inside?” she asks.

This question has been answered by Constitutional Court judge Edwin Cameron and his law clerks in April 2015, when they wrote about the “profoundly disturbing” conditions in Pollsmoor with its remand centre at “over 300% capacity” and its “filthy and cramped” cells. Inmates were reported to have “rashes, boils, wounds and sores” and the toilets were described as “deplorable”.

Court action was launched late last year to compel the Department of Correctional Services to resolve the problems in Pollsmoor.

Once visitors have been escorted inside the building and past metal detectors, there are more queues.

“It’s like we are their prisoners,” says an older woman who comes so regularly that she is even greeted by a guard.

She says that when she came the previous day, she didn’t even make it inside the prison as she came too late and the queue was too long. She says the guards said to those waiting outside that they’d come back and let more people in, but the guards never returned.

Everyone is searched. The guard shakes out people’s shoes and feels over clothes for any forbidden items.

“Why is it open?” the guard asks accusingly.

I’ve brought a bar of soap. The packaging is open. The guard smacks it vigorously against the side of the cubicle. There might be something hidden in the soap, she explains.

After the search, we wait. This is the official waiting section with pale green walls and long wooden benches on which visitors sit or lie. There is sickly sweet coffee pre-mixed with milk and sugar at a small tuck shop. One prisoner who is supposed to be cleaning the waiting area, continuously walks up and down, dragging a broom behind him.

A woman tells me her brother has been in the remand section since he was arrested in June last year. “Every time he goes to court, it is postponed,” she says.

A guard in a wheelchair calls out the names of about 40 inmates. About an hour later he returns and the next group of names is called.

The visitors walk through the grounds to the remand centre – an enormous face brick building surrounded by fences five metres high and guard towers.

Once inside, we are told to wait again. Visitors cram onto two benches outside the visiting room, trying to get as close as possible to the door so that they can be first inside.

When the door to the visiting room is finally opened, there is a frantic rush as visitors dash inside searching for the right face behind the glass. They know there will be barely enough time to discuss impending court dates, never mind the conditions of the inmates’ incarceration.

The visiting room is long and dimly lit, with grimy glass panes separating the inmates from the visitors. There are partitions to give some form of privacy between the visitors, but the sound of 50 or more people shouting at each other through a tiny metal grid in the glass is deafening. After what feels like barely 30 minutes, the lights are switched off. Most people know this means the end of their visiting time. In the gloom, with the only light coming from the windows on the other side of the glass where the inmates are, visitors say goodbye and slowly trickle out of the room.

The inmate I have come to visit isn’t behind the glass and I am told by a guard that “he didn’t respond” when the guards called his name. I am not the only one who is visiting a “non-responsive” inmate, and as we are left to wonder how an inmate cannot be found in a prison, the third and last group of visitors trudge into the waiting area.

It is now past 1pm and agitation and despondency is setting in amongst those still waiting for their visits.

One woman says that she has waited until 4pm to visit an inmate when the guards couldn’t find him because he was sleeping.

“I’m not leaving till I see him,” says another woman.

The guards at last locate the inmate I’ve come to visit. To hear him, I have to press my ear to the grid in the glass. When it’s my turn to speak, I need to shout directly into the grid, almost touching it with my lips. It makes what is an already awkward conversation even worse. It’s hard to make any eye contact.

The process has taken me eight hours, but now I must join another queue before the day is done. Goods that visitors have brought have to be searched before they can be handed over to the inmates. Visitors pass their containers of food, blankets and clothes through a hatch to a guard waiting in a small room, while the inmates peer through a barred gate at the other end of the room.

When I leave, there are still visitors waiting anxiously in the waiting area, hoping that the inmate they came to visit can be located.

As we walk out of the prison, a middle-aged man tells me he spent time in Pollsmoor when he was younger, and says: “I wouldn’t want my enemies to be in there.”