Nelisa Mpisekaya, a trader at the Cape Town train station, says food price hikes will be tough on her family. Photo by Sibusiso Tshabalala.

26 January 2016

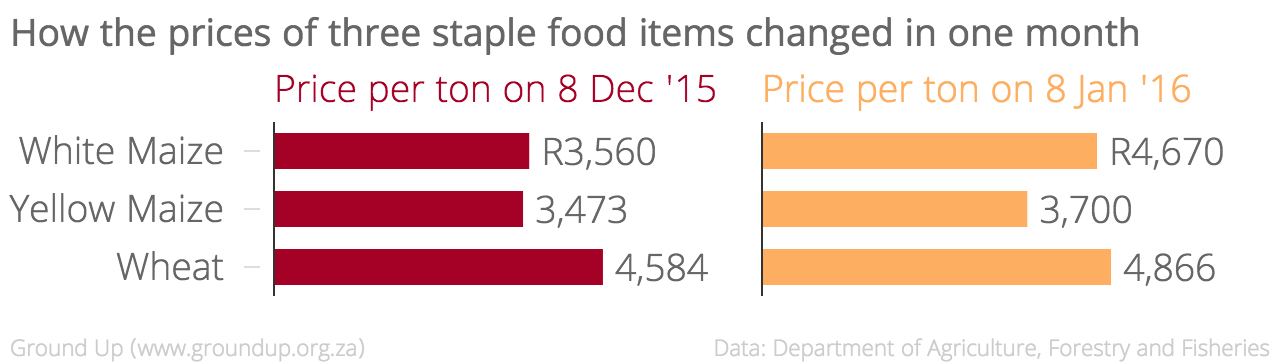

South Africa’s worst drought in 23 years is not only crippling rural towns and farmers. In urban areas, many poor and working class households are beginning to notice shifts in the price of their staple food items.

Matata Mbhele is a 52-year-old man who lives in Langa. Mbhele has had no formal work for 7 years. At the beginning of each week, he searches for temporary work, mostly in gardening and construction, to make ends meet.

“In a good week, I make R300. I spend half of this on food. Often, I buy a loaf of bread to sustain me.

Mbhele, like many working class and poor South Africans, is dependent on a set of basic staple foods, including: bread, samp and white maize for nourishment.

But with the current drought, Mbhele says he’s noticing an increase in the price of bread, his daily food staple.

“To save money, I always buy non-branded bread from Shoprite here in Langa. It is cheap and can sustain me for a day. I used to buy it for R6.50, but I now notice that the price is up to R6.99,” says Mbhele.

Matata Mbhele holds a loaf of bread. Photo by Sibusiso Tshabalala.

Speaking to GroundUp, GrainSA economist Wandile Sihlobo said price hikes on food would continue until 2017.

‘The next 6 months will be tough for many South African households. According to our conservative estimates, the price of the food basket—which is the basic set of foodstuff each household requires to meet minimum nutritional standards—will rise by 30%.”

Nelisa Mpisekaya (41), a trader at Cape Town central train station, says rising food prices would make it difficult for her to provide food for her children.

“The money I make from trading is split between my weekly stock and basic food items for my family. This month has been particularly tough: kids need to go back to school, and I’ve started trading later than usual this month because of the December holidays,” says Mpisekaya.

Mpisekaya spends at least R 400 a week for her three children and herself, and spends most of her budget on staple items like mealie meal, bread and rice.

“Sometimes, I shortchange my grocery budget and spend on my trading stock, in the hope that I’ll be able to make up for it on my sales, particularly at the end of the month,” says Mpisekhaya.

This phenomenon is not unusual. The 2015 Pietermaritzburg Agency for Community Social Action Food Barometer shows how many low-income households underspend on food by 55%, as food is often prioritised last.

“An increase in prices will be tough. I have a fixed amount of money I spend on food each month, I don’t see this increasing. I work for myself; no one gives me a raise.”

To counter the effects of food price hikes, 41-year-old mechanic Alfred Mulinga plans to buy non-perishable items in bulk, and find substitutes for expensive foodstuffs.

“I am cautious about my spending habits, since I live alone. So my plan is to buy non-perishable items like mealie meal and rice in bulk, so that I don’t have to frequent the store a lot,” says Mulinga.

He says he will go to sales to get more value for his spend. “This is my first shopping for the year. I’ve spent just over R400 for food that I’m hoping will last me for two weeks. But this doesn’t include items like meat and chicken.”

While the Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries has set aside R305 million to help farmers deal with the effects of the drought and curb rising food prices, Sihlobo argues that this may not be enough to avert a food crisis.

“In some ways government intervention is limited because we operate in a free market. The best government can do is to ensure that we have the proper rail and road infrastructure to get maize, wheat and other imports quicker throughout the country,” says Sihlobo.

This year alone, South Africa will have to import 5 million tons of white maize and 1 million tons of rice to meet consumer demand.

“While imports may be the way out, since we haven’t been able to reap good crops domestically, households will carry the price burden of the import costs. And it is the poor who will struggle the most.”