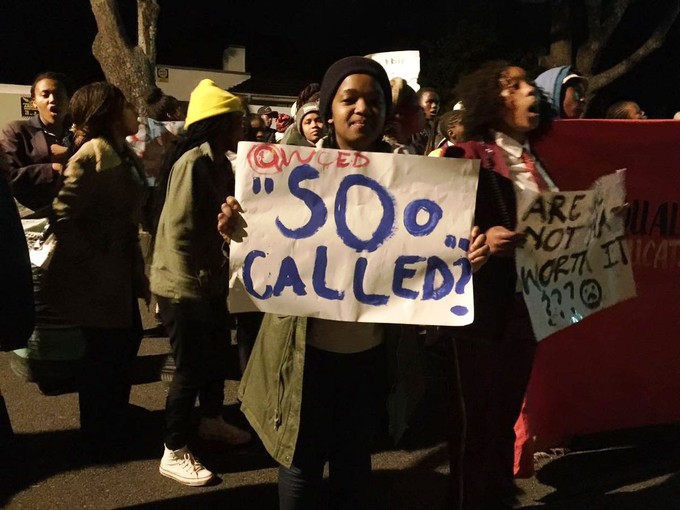

Students protesting outside Western Cape MEC for Education Debbie Schafer’s residence. Photo: Equal Education

6 July 2016

On Thursday 30 June at around 6am, a group of about 80 Equal Education (EE) members, mostly black high school learners, arrived at the home of Western Cape MEC for Education Debbie Schafer.

They posed no threat and made no effort to enter her property, sitting on the street in the pre-dawn cold, sometimes singing, waiting to hand over the social audit they had conducted into 244 of the Western Cape’s public schools. They did this because the results of this damning audit, which was presented to her department, were ignored.

Instead of engaging with them, Schafer tweeted at the seated learners, calling them an “illegal march”, accusing them of unknown “motives”, and labeling them “pathetic”. She then had a line of a dozen policemen shield her from the sitting children as she walked to her car. Throughout she refused to engage them.

When accused of ignoring the learners, while driving off she sent a smirking tweet reminiscent of Marie Antoinette: “I waved” she said.

Decent people can no doubt disagree over whether a politician’s residence is an appropriate place to deliver research findings and a memorandum. The EE members I have spoken to, who are serious and responsible young people, justify it on the basis that Schafer had ignored their submissions, been publicly rubbishing their work, and grossly misrepresenting it. Moreover, that her attitude towards them had been one of profound indifference encapsulated in the “I waved” tweet, representing the smugness of suburban privilege that can and does ignore township youth and their daily struggles.

The social audit is a methodology EE has used with success elsewhere. In Gauteng, three audits were conducted into the crisis of school sanitation, resulting in meaningful engagement with the political leadership and millions of rand spent to bring relief to learners.

A social audit involves citizens as trained researchers, not unlike the way the government conducts the national census. Experts conduct training workshops and review the methodology and findings. The information-gathering sheets used by EE for interviewing school principals, learners, and recording the auditor’s own observations, are fairly comprehensive. This is what Schafer (on June 16 no less) referred to as a “so-called social audit”, a disparaging term also used by her political principal, Premier Helen Zille.

In 2012, the National School Violence Study found that the Western Cape is the worst province in terms of learners being threatened with violence. EE’s Western Cape audit found that only half of schools have a fence that can protect learners and just 47% employ a security guard. Given the centrality of school safety in their daily lived experience, EE’s Western Cape members decided to campaign on this issue. 2,000 members marched to deliver these findings to three of the province’s eight district directors, among the highest ranking education officials in MEC Schafer’s administration.

These district directors received copies of hundreds of interviews conducted. Furthermore, they were also presented with this data arranged by district and school, accompanied by a code book for ease of use. For further ease, an accessible summary of the key findings accompanied the report. This data is publicly available and viewable on the EE website, with the school names and security details redacted.

Students outside Western Cape MEC for Education Debbie Schafer’s residence. Photo: Equal Education

Students outside Western Cape MEC for Education Debbie Schafer’s residence. Photo: Equal EducationSchafer and her spokesperson denied receiving this data, denigrating the audit repeatedly as mere “loose papers”. By 1 July, Schafer finally conceded the existence of the CD which EE had handed over, but continued to delegitimise its contents.

Schafer had not only misrepresented the truth but had demeaned the personal testimonies of hundreds of young people who had written of their experience in the hope of being heard. Even if it had been just “loose papers”, would that not warrant respectful engagement too?

The trend of modern democratic leaders is to be in touch with their constituents. Barack Obama and Jeremy Corbyn regularly make reference to letters from citizens, which they encourage and read on a daily basis. Debbie Schafer’s response to the contrary is arrogant and patronising: “Vague allegations that we know about. Very little new.”

The MEC has repeatedly stated that EE should have sent the data directly to her. EE’s reasonable response is that they gave it to those (district directors) responsible for implementing school safety policy. EE’s eventual approach to the MEC reflected a frustration generated by two months of non-response, despite having followed up, and the hope that she would hold her senior officials to account.

Her repeated insistence that EE should have additionally delivered the audit to her exposes her lack of confidence in her own senior officials. Perhaps EE should have sent Schafer a copy, but a social movement cannot bear responsibility for a lack of communication within a government department. Disappointingly, it is Schafer’s entire approach to this issue which is disconcerting as an MEC out of touch with the concerns of the poor. The opportunity for Schafer to work constructively with Equal Education is still alive.

Panyaza Lesufi, as spokesperson for Angie Motshekga, styled himself EE’s public enemy number one. But since becoming MEC for Education in Gauteng in 2014, he has constructively engaged with EE and accepted their demands, to the benefit of learners and education in Gauteng. This gives the lie to Schafer’s assertion that “nobody else gives them time of day”.

EE’s sole agenda is to improve educational opportunities for learners in poor communities, not the various conspiracies attributed to it by Schafer. EE has proven that it holds no allegiances to any political party.

EE’s audit found that corporal punishment occurs in 83% of schools – daily in 37% – and that learners have experienced or witnessed a violent event at 89% of schools. Yet when confronted with an instance of violence taking the life of a pupil, Schafer’s cold reply is that it is “not an education issue”. She deflects by asking when EE is “going to hold national government accountable for failing to resource SAPS in West Cape”, seemingly unaware that EE is doing just that by taking the national Minister of Police to court over unequal allocation of policing resources.

Any number of other deflections and attempts to impugn EE’s work and integrity have littered the social media output of Schafer and Zille in recent days. Some of them, it has to be said, suggest a sense of disgust and contempt for the right of working class black people to hold elected officials accountable. On display has been a callousness we’ve come to expect from the likes of Bathabile Dlamini and Blade Nzimande. As the political authority for education in this province Schafer has to be held accountable. In fact EE is doing work that her department should be doing in the first instance.

Reflecting on the tense 18 months that preceded the Soweto Uprising, historian Noor Nieftagodien writes:

“The white authorities maintained their ideological intransigence and were impervious to appeals even from moderate voices in the township. Their standard response to objections raised by parents and students were to dismiss them and, when further opposition was raised, to silence the voices of dissent through intimidation. The arrogance of the state in dealing with the legitimate concerns of students and parents is sometimes ignored as a critical cause of the radicalisation of students.”

There is a disturbing echo here in the way the learners from Khayelitsha, Mitchells Plain and across the province are being treated. All democrats who value accountable governance, equality and justice would do well to remind the MEC of this and that government should work for the people.