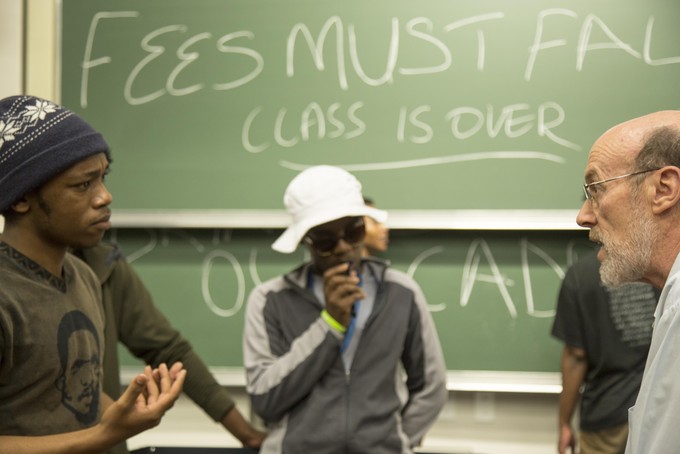

Student protesters and a lecturer debate. Photo: Andrea Teagle

4 October 2016

September’s resurgence of the Fees Must Fall protest on university campuses countrywide has been ushered in on a wave of violence by and against students. As experts debate the possibility of free education for South Africa, the country’s failures to adequately address the root causes of the fees problem are finally catching up to it.

Footage of stand-offs between heavily armed police and students wielding projectiles have dominated social media ever since Minister of Higher Education Blade Nzimande’s address on 20 September.

Earlier this year South African Students’ Congress (Sasco) warned of more severe protests in the event of a fees increase, and protests in anticipation of the announcement began at the University of KwaZulu Natal (UKZN) in August, spreading across the country within weeks.

When Nzimande announced that households earning below R600,000 per annum would be exempt from paying the 8% fee increment required by tertiary institutions, he also said government would subsidize the shortfall resulting from lack of funds.

But then he passed the buck of deciding how much to increase fees by to the institutions themselves, washing his hands of the free education debate.

“We have looked at the challenges at hand from all sides and have concluded that the best approach would be to allow universities individually to determine the level of increase that their institutions will require to ensure that they continue to operate effectively and at least maintain existing quality – with the caution that this has to also take into account affordability to students‚ and therefore has to be transparent‚ reasonable and related to inflation-linked adjustments,” said Nzimande.

“Our recommendation is that fee adjustments should not go above 8%.”

Fees Must Fall Protesters immediately made their dissatisfaction known. Protesters shut down a number of the country’s universities by blocking entrances, disrupting lectures, burning facilities and clashing with private security companies and police. At one of the chaotic campaign’s lowest points, cleaner Celumusa Ntuli died after inhaling fumes from a fire extinguisher, released by protesting students inside a Wits University residence. Days later, footage of policemen firing rounds of rubber bullets at Rhodes University students went viral. Across the country, campuses burned and learning ground to a halt.

From the visuals making their way onto the internet, it appears nothing about the fight over fees has changed. But in some ways the ‘Reloaded’ protests are different to those of 2015. Private security companies employed by institutions to protect property have been accused of ramping up the use of force against protesters. Suspensions, expulsions, interdicts and arrests have fractured the movement and rendered students less mobilised — and more angry.

“We’re saying that we don’t want to have free education in our lifetimes, we want free education now - because right now we are suffering. Right now. So we want fees to fall now. We’re tired of waiting for these hopeful dreams, for contracts, and two year plans to implement,” said Zola Shokane, a UCT student and prominent FMF member who was interdicted by the university and expelled.

Shokane’s dissatisfaction, voiced by students across the country, has drawn them into conflicts with police and security that have often been exceedingly violent.

“It’s been extremely disturbing to see just how brutal the response of the state has been,” said Dr Richard Pithouse, a lecturer at Rhodes University, who added that peaceful protest - often wrongly depicted as violent by the media - frequently becomes violent only when police exercise a disproportionate amount of ‘crowd control.’

“A clear distinction has to be drawn between protests to which the police respond violently and the protest becoming violent,” said Pithouse. “The media frequently, not just on campus but generally, will describe a protest that was peaceful until it was attacked by the police as having turned violent. So we need to be very clear about all those conceptual differences.”

After two years of clashes and no solutions in sight, it appears students, universities and government are unable to find common ground.

“You’re talking about a system that involves thousands and thousands of people, like any bureaucratic system,” said Professor Hlonipha Mokoena of the University of Witwatersrand.

Mokoena is chair of the Wits Panel on the Funding of Higher Education, which submitted a report to the Fees Commission at the end of June this year. She expressed the importance of negotiation in the call for fee-free education.

“Ultimately, power rests with exactly those insignificant pieces of paper called legislation,” she said.

“Ironically the most radical things happen around negotiating tables.”

But some student protesters say they are tired of talking. “When we thought we were progressing we thought we may need to fight other struggles,” said Lindiwe Dhlamini, a UCT student and social justice activist who explained how intersectionality came to be the key word for the student movement since the inception of Rhodes Must Fall and beyond, into Fees Must Fall.

“Everybody has their own idea of what it means to be an intersectional movement. To me it was a movement where we treat each other as humans, because first and foremost we’re human and we respect each other and check each other’s privileges.”

“We’re seeing students respond in the only way in which they can,” said Alexandria Hotz, one of the five students interdicted by UCT which eventually resulted in her expulsion. “Because we’re powerless beyond us protesting and putting our bodies on the line to demand free, decolonised education.”

While protests continue with no conclusion on the cards, it is unclear as to whether an agreeable way forward will emerge any time soon. Minister Blade Nzimande’s announcement was a testament to that.

“The Minister’s announcement addressed a very short term issue and that was the fees for 2017. He did not address the long term issue of the funding of higher education,” said Dr Max Price, Vice Chancellor of UCT.

Price has since announced that the university may well shut down until next year, should protests continue, rendering a short-term solution all but useless.

This video was shot while UCT was closed. It is open again at the time of publication.

During the early days of Fees Must Fall 2015, Daily Maverick published an article on research conducted by the South African Institute of Race Relations, suggesting that fee-free education for all undergraduate students was feasible in South Africa. The article illustrated numerous ways through which government could implement it.

“I don’t think the affordability issue is an issue. I think the real issue is the ideological one about what you are trying to achieve with a free higher education sector,” said Professor Mokoena.

She argued that, while fee-free education is possible, it cannot be achieved overnight.

“Of course, it’s affordable. Of course the state can come up with R9 billion if it wants to — but the issue is what is it for? That is when you get into the complicated issues and this is why it is that the decision cannot be made overnight,” said the Professor.

Fee-free education needs to be a means to an end as opposed to a decision based on the assumption that South African graduates will remain in the country and contribute to the growth of the local economy after receiving their qualifications, she added.

“(Fee-free education) is based on the assumption that you’re going to have economic growth. That the people that you are educating are going to pay taxes, that they are going to contribute to the revenue. And these are all assumptions that are not necessarily going to happen just because you’ve put in fee-free education,” said Mokoena.

“If you look at the rest of our continent, what happened in the 1960s and 1970s after the colonial period with independence, a lot of African countries ploughed a lot of money into higher education — and yet we have a deficit of professionals on the African continent,” she added.

But free education would “proportionally privilege the privileged,” said Director of the Centre for Higher Education Trust, Dr Nico Cloete, in a presentation to the Commission of Inquiry into Higher Education last month.

South Africa has the highest rate of private returns to higher education in the world, but also the highest levels of inequality. Because free higher education in Africa has traditionally been built on “inequitable social structures,” encouraging “the perception that the state is providing something people want… free higher education in highly unequal societies mainly benefits the already-privileged, who have the social, cultural and economic capital to access, participate and succeed in education,” his presentation stated.

This is not unique to South Africa, he further said, citing studies showing that, globally, the poorest citizens don’t get excluded from higher education just because they can’t afford it, but because they do not qualify for it.

Cloete proposes a “sliding scale” ranging from R150,000 for wealthy students to R15,000 for the poor, as well as a contribution by government, business and civil society to higher education.

Meanwhile, it is unclear as to when and how the current impasse between state, students and institutions will be breached, in spite of the efforts that have been made to consolidate the different views expressed.

“To me it seems that we’re heading towards a stalemate at the University Currently Known As Rhodes. There are students who are resolved to keep protesting. There’s a similar resolution on the other side that things must carry on as normal,” said Dr Pithouse.

“I don’t see anything good coming out of that stalemate and I think ultimately it will be managed with violence from the state. And that’s obviously not a positive way forward. ”