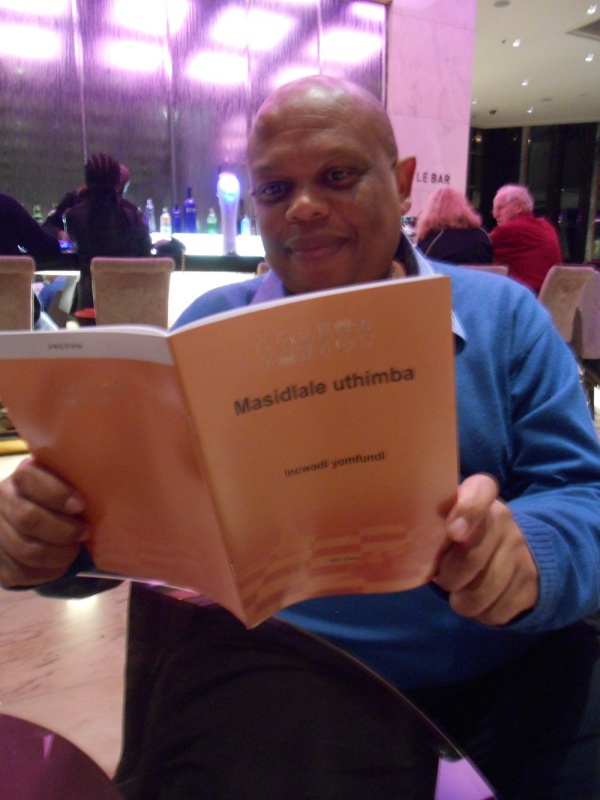

Photo by Mariska Morris.

10 July 2015

International Chess Master Watu Kobese sits on a luxury couch in the Cape Sun Hotel, where the South African Chess Open is taking place. It is an hour before he competes. He has agreed to meet to discuss his life, South African chess and Masidlale Uthimba (Let us play Chess), the first isiXhosa chess book. It was launched on Tuesday (7 July).

“I started playing by watching my dad. The whole chess thing came in 1972 when the official Spassky match captured everyone’s imagination, including South Africa,” the 42-year-old chess star says.

During the Cold War, Boris Spassky from the Soviet Union played against Bobby Fischer from America for the 1972 World Chess Championship title in Iceland. It was dubbed the match of the century, because the players were depicted as representing the protagonists in the cold war. Ironically though, Spassky had a tumultuous relationship with the Soviet authorities and Fischer eventually voiced support for the 9/11 terrorist attack. Fisher, a deeply troubled man but one of the three or four greatest players ever, won convincingly, ending the Soviet Union’s 24 year domination of the championships.

Arthur Kobese, father of Watu Kobese, and his friends started chess clubs in Soweto shortly thereafter. “They would play in different homes as a virtual club so to speak. When they were playing, I watched. From there, I started playing,” says Kobese. His father died in 2010. Kobese says he was lucky never to have played his father in a tournament, yet the memory of his father and friends playing chess partly inspired Masidlale Uthimba.

“If you look at all the board games in the townships, in the rural areas, it is exciting to watch guys play. They will be making jokes and singing. Chess was not much different which is maybe what drew me to chess. Besides the game, it was the atmosphere,” he said.

Kobese believes language is a barrier that prevents young children from learning and understanding the game. He grew up in Soweto where English is prevalent due to “a lot of tourists moving around”. Children are surrounded by English and learn it quickly. However, in rural townships where children never hear English, it is difficult to explain the game with its obscure terminology. A lack of literature on chess written in indigenous languages got Kobese writing. He was careful not to directly translate terms, although some complex terms have been directly translated. For example, diagonal is translated to idiagonal.

Photo by Mariska Morris.

He says, “It is generally accepted that chess started off in India in a completely different form. They had boats, elephants and advisers to the king as their war formation, and they had different rules; the same idea, but with different rules. Slowly [chess] made its way to Europe. When it got to Europe it changed completely. It reflected the society that was there.”

“In English it is a Bishop. In German it is Läufer which is a ‘runner’. In Russian it is Slon which is an ‘elephant’. You realise that there is some kind of identification of a region of what chess is for them. That is what has made chess such an old and respected game, and has made it survive all this time. So, when writing the names, I made up new ones, a new dynamic that would make the game come alive for a kid,” he says.

“Check mate is thinjiwe. In the olden days when two kings fought, the aim was not to kill the other king, but to defeat him and once he was defeated he will be absorbed into the other kingdom. Once he merged, he would no longer be the ruler. That process was thinjiwe. It makes sense for checkmate. You never capture the king. You corner him and he gives up. From there, we decided that the game of chess itself should be uthimba which is the process of trying to get to thinjiwe,” Kobese explains. He hopes that these familiar terms will make chess more accessible to rural children. It is in the rural areas that chess is most needed according to Kobese.

Chess is thought by some to improve maths skills and develop logical ways of thinking among other things. The European Parliament voted to advance chess in European schools in 2012. Private schools throughout South Africa followed this initiative, including the German school in Cape Town where Kobese teaches chess as a subject. “[At the private schools], the children are going to pass and get maths anyways, but in the rural areas, in the township schools, it is non-existent and that is where it should be. My dream is for it to be in every school, for everyone to have access to the game,” he said.

Two hundred copies of Masidlale Uthimba were given to chess clubs, but Kobese hopes to promote the book in more rural areas and townships. “We need to go to a taxi rank, have a few people playing, talking, get the crowds going then demystify it, talking in their language. Going into different areas and promoting it. That is the next step,” he said. Kobese wrote Masidlale Uthimba nine years ago in isiZulu. He translated it to different languages. He wanted the terms he used to get official government acceptance. But this was difficult. “It was a simple thing of accreditation; a very simple process in my mind that was just not happening,” he says.

Kobese relocated to Cape Town, where he found support for his idea from the Western Cape government. He worked with Advocate Lyndon Bouah — also an excellent chessplayer — in the provincial government, and language specialist Xolisa Tshongolo, and had the support of Ivan Meyer, Provincial Minister for Cultural Affairs and Sport at the time. Kobese says Meyer’s attempts at promoting chess in the Western Cape made the provincial government receptive to his book and the new terminology. “I had to work hand in hand with their language department. It was a nice process actually,” he said.

Kobese no longer plays professionally. He does still compete and hopes to attend the 2016 Chess Olympiad hosted in Baku, Azerbaijan. “I still need to qualify, but I will,” he said. Preparing for the Olympiad is difficult as there are only a few high ranking players in South Africa against whom he can sharpen his skills. “Unfortunately, you can only go down [playing in South Africa]. The strongest players today are playing outside of the country,” he said.

Though he still has dreams of becoming an international grandmaster, the title above the international master one that he holds, Kobese’s dreams now lie with the development of chess. He says, “If there is anybody in South Africa who has a talent for chess — doesn’t matter [what] race or class — that person should have the opportunity to fulfil their potential. As long as I am around I will try to get that done.”