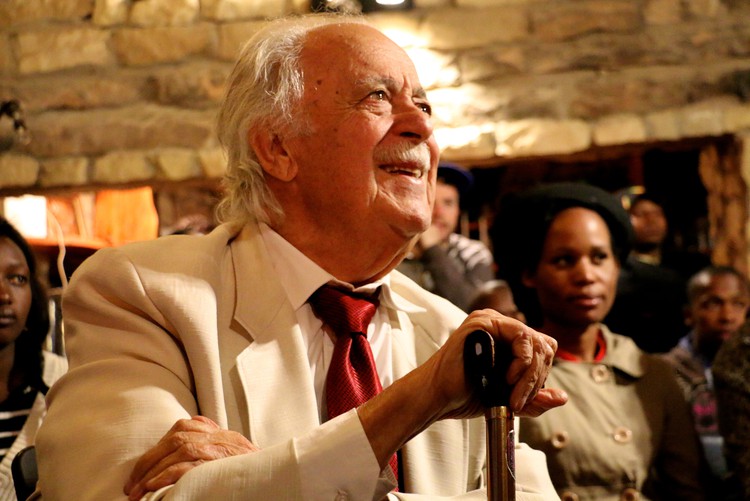

Renowned human rights lawyer George Bizos turned 90 on 15 November. Photo: Flickr Aya Chebbi (via Wikipedia, CC BY 2.0)

14 November 2017

George Bizos is one of the most celebrated lawyers in South Africa. He was part of the team that defended Mandela, Sisulu and others at the Rivonia Trial and helped to ensure that they were spared the death penalty. He defended the United Democratic Front (UDF) leaders at the Delmas Treason Trial and represented Steve Biko’s family at the inquest into his death. Throughout his life he has defended poor people.

There is no profession which requires more hours of reading than law, and not just any reading, but careful reading over every word to find the missing fact, the legal opening and the winning line of argument. Yet Bizos nearly stopped reading at a primary school level.

Bizos grew up in a small rural village in Greece. As he tells us in his autobiography Odyssey to Freedom, he faced great odds:

“My primary school was not unlike those the children of Soweto attended during the apartheid years. In the 1930s there were no fewer than a hundred and forty of us of different ages in one room with a single teacher. A blackboard, an abacus and a slate were the main teaching aids. A tattered reading book was passed from one year to the next, while a new exercise book, a pencil and an eraser were all we had.”

But Bizos was also very lucky. His father was mayor of the little village. Therefore, Kyria Eugenia Kotsakis, who they called Daskala –- the teacher –- stayed in their house. This meant he got a lot of extra instruction and attention.

As Bizos recalls:

“She managed the school with ease and grace. We were not afraid of her. Before we arrived at school she wrote exercises on the blackboard for the older ones to do on their slates or in their books, then she read lessons to us, the younger ones. She set exercises then moved to another age group and more advanced work.

Daskala secured our discipline by appealing to our better natures.”

Bizos continues:

“The worst physical punishment she ever imposed on anyone was three moderate smacks with a flat ruler on the palm of the offender’s hand – but she was capable of administering tongue-lashings which put us to shame.”

Right-wing Royalists started to gain power in Greece and Bizos’ father lost his position as mayor. On top of this, his family was poor. One day the school principal called Bizos’s father in and asked him to replace his son’s old and tatty shoes.

Bizos had to leave home to pursue his studies. His father sent him to Kalamata where Daskala now lived. Bizos failed the entrance exam and therefore had to begin again in first grade.

During these years fascism was rising in Europe and then WWII broke out in 1939. One day it was reported to Bizos’ father that a shepherd had seen a group of hungry, frightened men hiding in the hills. In fact, these were New Zealand soldiers who had been fighting to protect Greece from Germany and Italy, and were evading capture. Young Bizos and his father set out to find them, carrying food. This encounter led to one of the many daring and selfless acts of the war: Bizos’ father used most of the family’s savings to buy a boat to help the New Zealanders sail to Crete, an island that was still under Allied control. Many of the villagers helped in this effort, providing food and finances. This heroic journey successfully rescued the soldiers, when a British naval fleet found the little boat. George and his father climbed aboard with the soldiers and were taken to Alexandria in Egypt. Bizos’ father did not see Greece or his wife ever again.

The two were told they could not return to Greece until after the war and so elected to go to South Africa. There Bizos’s father took small jobs and tried to make ends meet. George was looked after by members of the Greek immigrant community in Johannesburg. He would work in shops, and do odd jobs, but education was not very high on his priority list. He and his father achieved some fame when a Sunday Times journalist discovered their heroism and published the story with a picture.

At that time the likelihood was that Bizos would never finish school. But as he tells us, “chance would have it otherwise”.

“One day, while serving a customer, I noticed a young woman in the middle of the shop staring at me. She was wearing a blue blazer with white and yellow stripes and a badge on the pocket with the head of a goat sporting long, upward-turned horns. There was a motto underneath but I couldn’t read it, much less understand what it meant. As she waited her turn she stared at me. When I served her, she turned her head sideways, smiled and asked, ‘Are you not the boy whose photo appeared in the newspaper? With your father? The ones that escaped from the Germans?’ I said I was. With an even broader smile she reached across the counter to shake my hand. ‘What school do you go to?’ I told her that I didn’t go to school. She asked to speak to my father and, when I said he worked in Pretoria, she waited for Mr Bill to finish serving the customer.

She introduced herself as Cecilia Feinstein, a teacher. Although the shop was busy – it was late afternoon and many people got off the tram at the nearby shop – she bombarded Mr Bill with questions about me and my father. Why was I not at school? How could she get in touch with my father? How old was I? … Then she said she would come back in a day or two, by which time she hoped all would have agreed that she could take me to her school the following Monday.

… The young teacher came back and was delighted to hear the decision. Would I put on my best clothes, including the cap I wore when the newspaper photograph was taken, and be ready at seven the next morning? She would take me to Malvern Junior High, a school offering standards six to eight.”

George joined Feinstein’s class, and after a while, he began to flourish.

By 1943 Feinstein told George that she was engaged to be married, and would no longer teach the class. But she continued to play a pivotal role, as George remembers:

“I told her of my father’s wish that I become a doctor, and she said she believed I could do it. Such encouragement was new to me. When I had ventured to write about my dreams for the future in a class essay, my English teacher had added a note at the end saying that I was building castles in the air. Miss Feinstein said that she did not mean to criticize the school, but that for my dreams to come true I should go to a proper high school where I could matriculate. If my father and I agreed, she could arrange for me to start standard eight at Athlone High School…”

Thirty years later Bizos decided to track Cecilia down. He called, but did not find her at home, but she returned his call. On the phone she said:

“I thought that it must have been you who phoned earlier, but I just couldn’t wait anymore. I so badly wanted to speak to you. I have been following your cases, and I am so proud of you.”

“And I am so grateful to you,” [Bizos] said. “If it had not been for you, I don’t know what I would have done with my life.”

Many years later, in 1996, the University of Natal in Durban conferred an honorary doctorate of law on George Bizos. He was asked which special guest he wanted to invite to the ceremony. Cecilia Feinstein was top of the list. Finally, after more than fifty years, he was able to make a public acknowledgment of her role in his life.

Bizos recently wrote, “I often wonder what I might have made of my life if she had not insisted that, refugee or not, I was entitled to the right to learn.”

George Bizos is a South African hero. He faced daunting odds but climbed out of adversity to succeed. He suffered hardship but he was also lucky. People came into his life at the right moments and helped him to get a good education. He was an immigrant child who met someone who saw potential in him instead of otherness, and offered hospitality instead of xenophobia.

Today, as in the past, there are many young people as bright as George Bizos who never get that chance in life. One of them was named Michael Komape.