29 June 2022

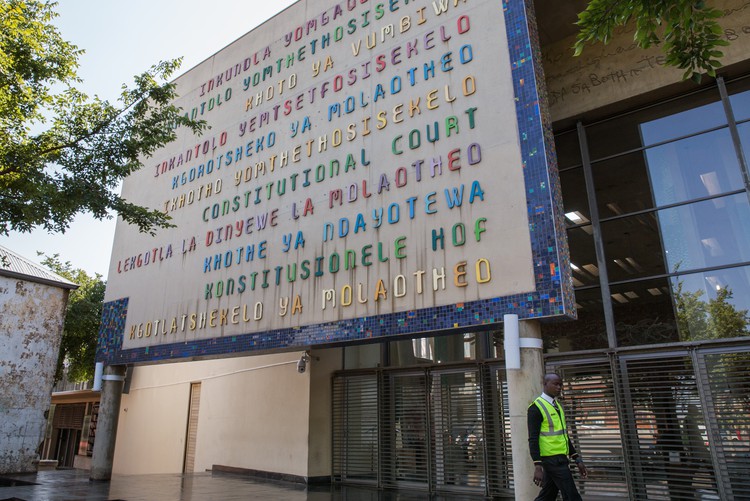

The Constitutional Court has given legal recognition to Muslim women married in terms of Sharia law, and also their children. Archive photo: Ashraf Hendricks

The Constitutional Court has confirmed the Supreme Court of Appeal’s ruling that the Marriage Act and the Divorce Act are unconstitutional for failing to recognise Muslim marriages.

The Women’s Legal Centre Trust and Muslim Assembly Cape had argued that not recognising Muslim marriages left women without legal protection.

The Association of Muslim Women of South Africa opposed the application, saying “disgruntled Muslims or modernists” could simply conclude marriages under the Marriage Act.

The Constitutional Court said it was not ruling on the constitutionality of Sharia law but only considering the hardships faced by women and children excluded from the benefits of the two acts.

The Constitutional Court has given legal recognition to Muslim women married in terms of Sharia law, and also their children.

In an unanimous judgment, the court has confirmed that the Marriage Act and the Divorce Act are unconstitutional in failing to recognise Muslim marriages which have not been registered as civil marriages.

The court further declared as unconstitutional sections of the Divorce Act which fail to provide mechanisms to safeguard the welfare of children born of Muslim marriages, and fail to provide for redistribution of assets.

While the court suspended the declarations of invalidity for 24 months to allow for the legislation to be amended, it ruled that pending this the provisions of the Divorce Act shall apply to all marriages from 15 December 2014 “as if they are out of community of property”.

The matter came before the apex court for confirmation of similar orders made by the Supreme Court of Appeal. However, the Constitutional Court went further, and granted interim relief.

The application, launched by the Women’s Legal Centre Trust, had its genesis in applications in the Western Cape High Court which were consolidated for hearing. They involved Muslim women married in terms of Sharia law, who complained that they had been discriminated against because they had no legal protection.

One had been excluded from inheriting from her late husband’s estate. Another had been precluded from benefiting from her husband’s pension fund.

In its initial stages the application was opposed by government, including the President and the Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development, who said the state had no obligation to initiate and pass legislation to recognise Muslim marriages.

At the Supreme Court of Appeal, however, both conceded that both acts infringed on the constitutional rights to equality, dignity and access to court. They also conceded that the rights of children were similarly infringed.

Writing for the court, Acting Judge Pule Tlaletsi said the main opposition had come from the Lajnatun Nisaa-il Muslimaat (Association of Muslim Women of South Africa) which argued that most Muslims did not consider the non-recognition of their religious marriages to be discriminatory.

They argued that there was a simple solution for those “disgruntled Muslims or modernists” who sought recognition - and that was to get married in terms of both Islamic law and the Marriage Act.

The Muslim Assembly Cape (MAC), admitted as an amicus curiae (friend of the court), argued that while Sharia law addressed and encouraged marriage contracts, they were “not the norm” because women did not have the means to conclude them, and often did not have any bargaining power.

MAC also raised the substantial harm and prejudice to women and children.

“As an institution that deals with these issues daily, it stated that it is often powerless to compel forfeiture or maintenance for wives and children … and that often the most it can do is to advise the husband to do what is right,” Judge Tlaletsi said.

“Most worrying, however, it notes that it is also powerless as regards overseeing the visitation of children where it has been made aware that a husband has, in the past, been physically violent.”

Judge Tlaletsi said Muslim marriages had never been recognised as being “valid” - and this situation continued to date, 28 years into democracy. While, in theory, women could opt to also marry civilly, this was often not a meaningful choice. Their exclusion of protection provided for in both acts was discriminatory.

It often left women destitute, or with very small estates, upon talaq (divorce).

Regarding the attitude of the Lajnatun Nisaa-il Muslimaat, the judge said: “It is important to make the point that whether discrimination exists does not depend on the subjective feelings of various members of the affected group.”

He said not recognising such marriages as being valid sent a message that they were not worthy of legal recognition or protection. The retention of such a status would support “deep-rooted prejudices”.

“The views of those willing to live under the status quo cannot prevail over the extension and protection of constitutional rights to others.

“Women in Muslim marriages must be fully included in the South African community so they can enjoy the fruits of the struggle for human dignity, equality and democracy,” Judge Tlaletsi said.

He noted that Muslim husbands had the power to obtain a unilateral divorce through talaq and that the State had failed to provide any mechanism for the resolution of disputes relating to this.

“It should be made clear that the Constitutionality of Sharia law is not under consideration. We are concerned with the hardships faced by women (and children) as a consequence of being excluded from the benefits (of the two acts).”

The court also ruled that the common law definition of marriage was also unconstitutional insofar as it failed to recognise Muslim marriages as valid “simply because they are potentially polygamous”.

While the trust wanted an order that the recognition be backdated to 1994, Judge Tlaletsi said given the rights of third parties which could be implicated by that, it was necessary to strike a balance.

The order, he said, would apply to all unions validly concluded in terms of Sharia law and subsisting at the date that the Trust instituted its application in the High Court (15 December 2014). It would also apply to marriages no longer in existence, but where proceedings have been instituted and not finally determined.