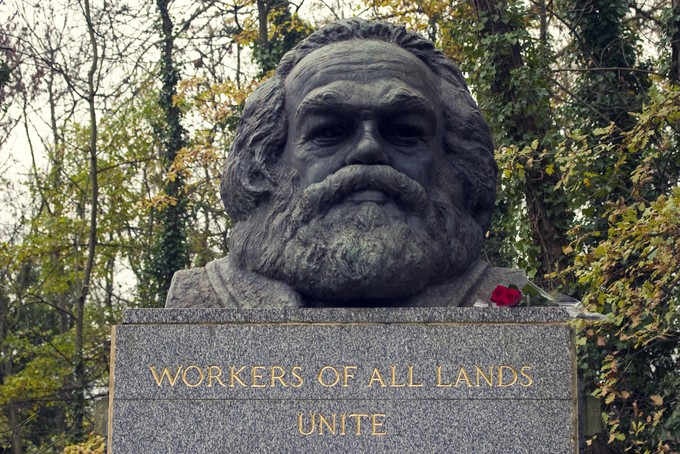

Photo: Ann Wuyts via Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

18 May 2016

Workers’ Day — May Day — came and went. And for all the calls and claims to unity, division and confusion seemed to dominate. Not only in South Africa, but throughout much of the globe.

This is hardly surprising given the ongoing economic crisis, with the massive loss of jobs and few prospects of any change: the system classified as neoliberalism continues to triumph and to sow havoc, especially among the vast army of the sellers of labour. And the desperation this breeds opens the way for demagogues and fundamentalists of every stripe to lead in the direction of strife and the prospect of barbarism where it does not already exist.

The situation is exacerbated by the elites and their supportive governments in developed countries that play the role of political puppet masters while supplying weapons and finance and operating the drones that kill, all too often indiscriminately.

Small wonder then that organised workers, perhaps at a greater level than before, have turned to the analysis offered more than a century ago by Karl Marx and, although, largely overlooked, his collaborator, Frederick Engels.

It was their analysis that provided much of the impetus for the early trade unions. In particular the final cry of the Communist Manifesto they authored and that was published in 1848: Workers of all countries, unite.

And it is not only trade unions. Last week in Johannesburg there was a celebration of the birthday of Karl Marx hosted at the University of the Witwatersrand by the Ikwezi Institute. It was the introduction to a series of symposia about economic alternatives. Such discussions include that standard bearer of liberal economics, Adam Smith.

However, in the United States, for example, there are now only two books more frequently assigned to students in US colleges than the Communist Manifesto.

These are “The Elements of Style,” the writing guide by William Strunk, and “The Republic,” by Plato.

Which is not to say that there is a sudden lurch to the left in a country that offers as probably presidential alternatives, Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton. But it does appear to indicate a search for an alternative in much the same way as do ascents to political prominence of the likes of Jeremy Corbyn in Britain, Bemie Sanders in the United States and Julius Malema and his Economic Freedom Fighters on the home front.

However, in South Africa, we are used to the name of Marx being trotted out by Cosatu leaders, usually coupled with that of VI Lenin. Many of the individuals mouthing these names are members of the SA Communist Party (SACP). This is a party that also lays claims to “Marxism-Leninism”, as, indeed, does the leadership — although they are no longer SACP members — of the metalworkers’ union, Numsa.

They were expelled from Cosatu and are now the leading driver for a new, “independent” trade union federation.

Some of the calls that use the name of Marx, especially linked to Lenin, are often vague and bring to mind a comment once made by Marx in 1888 about a group in France who professed to be followers of his ideas: “What is certain is that I myself am not a Marxist.”

There is also the standard, bigoted reaction to Marx, usually by people with preconceived notions and no real idea about what Marx —or Engels — wrote or stood for. Here we have images of the Devil incarnate, combined usually with quotations taken wholly out of context, a favourite being “religion is the opium of the people”.

Marx actually wrote: “Religion is the sigh of the oppressed beast, the heart in a heartless world, the opium of the people.” Which is rather different, considering that opium was the only painkiller known in those days. A latter day interpretation might be: “Religion is the paracetamol of the people”. In other words a necessary painkiller, but not the solution to an underlying illness.

So whether one agrees or disagrees with the ideas of Marx — and “Marxism” — it is essential, in the first place, to know what is being talked about. To do so, it is unnecessary to wade through the three volumes of Das Kapital or to seek comparisons with the earlier works. Marx and Engels summarised their ideas in that 1848 manifesto that predicted globalisation and the “absurdity” of an epoch of over- production.

They also foresaw that the march of technology would result in increasingly “paupering” the labouring masses. But they did not foresee the impact of the digital age or of the lunatic expansion of credit that would sustain a system arguably well beyond its sell-by date.

Their solution was for the extension of democratic control by instituting the rule (“dictatorship”) of the majority who sell their labour to survive for that of the dictatorship of the monied minority who make arbitrary decisions and who influence liberal governments. Can this be achieved? Should this be attempted? And, if so, how?

If not, what is the alternative to a system clearly in ongoing and probably deepening crisis? That is what Ikwezi and other initiatives are asking. And they are questions that should concern all of us.