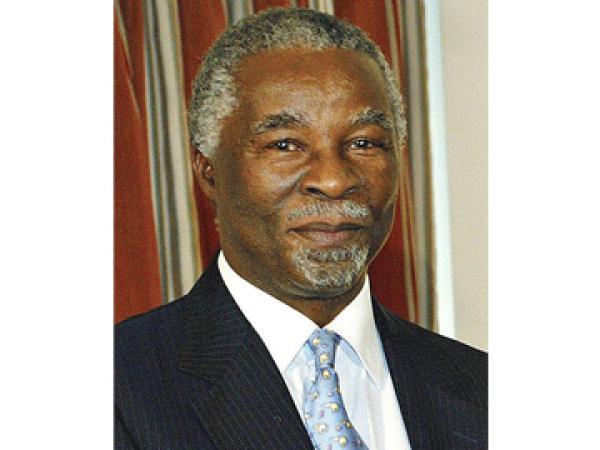

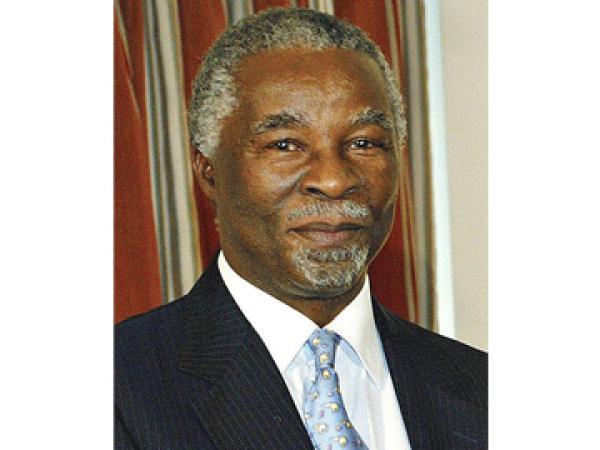

Former President Thabo Mbeki. Source Agência Brasil via Wikipedia under Creative Commons.

3 April 2014

As we head into elections, the ANC boasts about successes in the fight against AIDS and South Africa’s large antiretroviral treatment programme.

On the other hand, the opposition Democratic Alliance runs an advertisement that says under President Thabo Mbeki we saw progress, but now that progress is being reversed.

Both parties are being selective with the facts.

This week we have published two articles — here and here — on how South Africans are dying.

The good news is that we are living longer. Health is improving. The statistics show that there has been a rapid rise in life-expectancy, a vital measure of a country’s health.

Over two and a half million South Africans have died of AIDS according to best current estimates. Even the best run, best-intentioned response to the epidemic could not have prevented most of these deaths. Nevertheless, several hundred thousand deaths at least could have been avoided, maybe more than a million.

During his rule, Mbeki consciously defied the science of HIV and blocked the rollout, first of mother-to-child transmission prevention, and then of antiretroviral treatment, for people with HIV in the public sector. It was only after successful court action that drugs were provided to prevent mother-to-child transmission. It was only because of persistent protests culminating in the Treatment Action Campaign’s civil disobedience campaign of 2003 that Mbeki’s government relented –in fact his Cabinet rebelled against him– and treatment began to be made widely available in public health facilities.

Even then the health department stalled and the treatment rollout only began in March 2004 after the threat of court action.

Two separately conducted analyses using different methodologies, one by Harvard University researcher Pride Chigwedere, and the other by University of Cape Town economist Nicoli Nattrass, calculated that Mbeki’s delays cost more than 300,000 lives. These were conservative estimates. The real toll was likely much higher.

After the treatment rollout started, Mbeki’s government intensified its disinformation campaign against medical science. Senior government people including the Minister of Health, the late Manto Tshabalala-Msimang, openly encouraged quackery, such as the propaganda campaign of vitamin salesman Matthias Rath. We cannot know the number of people who were confused into taking deadly health decisions, but it likely was many.

This death on a mass scale was not merely a consequence of negligence or lack of capacity. It was the result of conscious decisions by Mbeki and Tshabalala-Msimang to ignore medical science, ignore the pleas of people with HIV and of doctors, and actively block access to medicine. The resources were available to provide medicines; Mbeki chose to block access to them in the public sector, with ghastly consequences.

The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, to which South Africa is a signatory, defines as a crime against humanity, “the intentional infliction of conditions of life, inter alia the deprivation of access to food and medicine, calculated to bring about the destruction of part of a population …”.

Whether this applies to Mbeki is worth debating. He undoubtedly did not want to cause the deaths of several hundreds of thousands of people, but he intentionally defied scientific medicine. The consequences were foreseeable. Mbeki gambled that his own reading of the situation was right and that thousands of the world’s best researchers were wrong. For this exceptional hubris, many died needlessly.

No one has ever been prosecuted for the AIDS denialist catastrophe. Many of those who supported Mbeki’s AIDS positions continue to lead successful public lives, to write, edit magazines, publish books, get invitations to speak, and mingle with those in the highest echelons of power.

Jacob Zuma was Mbeki’s deputy for most of the AIDS denialist era. He headed the South African National AIDS Council. Under his watch it wasted money and time. His notorious “shower” comment didn’t improve public understanding of HIV, though its destructiveness has been exaggerated.

Zuma shares responsibility for the AIDS denialist debacle.

But to his credit, it was he who intervened during the Treatment Action Campaign’s civil disobedience campaign and promised a delegation of the organisation’s leaders that Cabinet would change policy. For all his considerable faults, Zuma delivered on that promise.

So neither the ANC’s boastfulness about the success of its AIDS programmes, nor the DA’s pseudo-nostalgia for Mbeki are warranted. We shouldn’t forget the destruction Mbeki wrought.

Geffen is the editor of GroundUp. He used to work for the Treatment Action Campaign and serve on its secretariat.