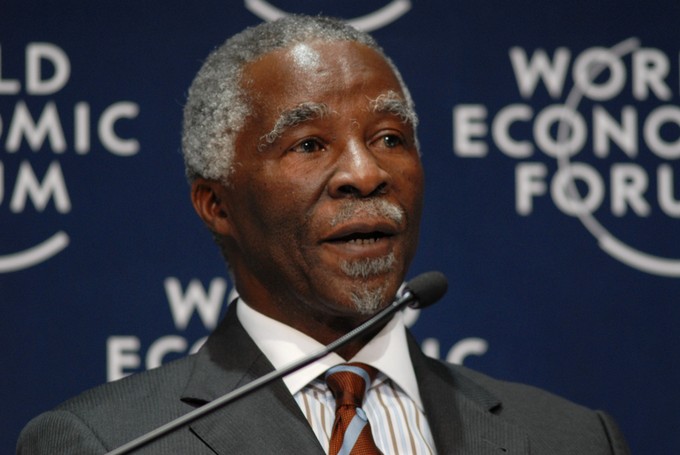

Photo: Eric Miller Wikimedia (CC BY-SA 2.0)

18 May 2016

Former president Thabo Mbeki’s criticism of South Africans who win land claims and opt for cash instead of land is misplaced, write Mzingaye Brilliant Xaba and Monty Roodt.

Praising the Zimbabwean graduates who built a thriving farm in Malmesbury, Mbeki said he was not surprised to read the GroundUp story because Zimbabweans are hardworking and have a positive attitude towards land. He said in South Africa, it appears that many people prefer money to land because land claims in South Africa have largely been settled through cash compensation, rather than land transfer.

Mbeki said, “It’s not any South African, but Zimbabweans who went to the farmer to say “can I use your farm” …because Zimbabweans have a different attitude to land. That’s why you find here many, many times, people make land claims, they get the land, but rather than getting the land, they say, ‘rather give us money’.

“If you look at the record of the land claims that have been settled over the last 22 years, you will find that in the majority of cases, the people who win the claim, they prefer to take the money, rather than keep the land and work the land. That’s the reality of South Africa”, Mbeki said.

His comments have been reiterated by others who are pessimistic about land reform.

We find this argument problematic in that it creates an impression that black South Africans do not want to farm, that they are too urbanised to farm or that they prefer cash to owning land. Most importantly, Mbeki’s statement also creates the impression that most of the claimants who chose cash compensation over land compensation did it unthinkingly or without due consideration of the implications of their actions.

In reality, the situation is far more complex. There are many reasons why claimants choose financial compensation over restitution of land. A large proportion of restitution claims are urban, and for many claimants, moving from one urban location to another would be as disruptive as the initial forced removal. It makes sense for these people to take the monetary compensation and plough it into their children’s education or into extensions to their existing home.

Even with rural claims, there are many obstacles for claimants to overcome if they want to get back their original land or get alternative land, make the physical move, re-establish themselves, and make a living from agriculture. Part of this problematic has its origins in the nature of apartheid: people were largely removed from land which was already inadequate in terms of size and infrastructure. Two or three generations down the line, claimant families have multiplied, descendants have integrated themselves into new communities, many have become urbanised, and the idea of returning to a underdeveloped piece of land barely known to the descendants does not always have the appeal imagined by armchair proponents of land reform.

Even where claimants are keen to return, the convoluted legalistic restitution process, the lack of commitment and capacity of the Commission on Restitution of Land Rights, the limited resettlement grants, and the almost total lack of post-settlement support, make it a daunting task. In some cases, as law professor Bernadette Atuahene has observed, claimants are willing to wait for the land from which they were evicted, rather than accept an alternative piece of land. Even where they are willing to consider alternative land, many claimants are discouraged by the difficulty of finding alternative land.

Where claimants have chosen cash compensation, it is usually because land transfer is a long complicated process and many claimants do not have faith in the Commission to deliver their land. Even those who have opted for land have in many cases come to regret it as the process drags on interminably.

Additionally, financial desperation caused by poverty (bearing in mind that most claimants are poor) has made waiting impossible. In most cases, cash compensation is made to look easier, definite, guaranteed and faster, while land compensation is made to look complex, and uncertain.According to Atuahene, there is also a belief that if you choose land, you will end up having to pay taxes and rentals to the municipality. In addition, older claimants feel that they are too old to go back and make meaningful use of their land.

Professor Andries du Toit, who led the 1998 Ministerial Review of the restitution process, pointed to the fact that many claimants were not properly empowered by Commission officials to make informed choices about the form of restitution available to them. In some cases, it is alleged that when claimants showed anger and frustration due to bureaucratic delays, the Commission officials coerced them to choose financial compensation to quicken their restitution awards.

As a parting note, we would propose that the Commission makes cash compensation, especially for rural claimants, a last resort, and only after a thorough appraisal of all land-based alternatives. We would also propose that it empowers claimants to make informed decisions within a framework of the active promotion of developmental land reform, with adequate resettlement grants, and the integration of the restitution process within the planning of municipalities, so as to ensure budgeting for bulk infrastructure and housing. In addition, restitution should be boosted by integrating it with land redistribution so as to ensure economically viable land holdings. Lastly, provincial Departments of Agriculture should be empowered to provide, serious post-settlement support and agricultural extension services.

It is an insult to the dignity of black communities, given the history of land dispossession, to say that people who were robbed of their livelihoods through forced removals should be compensated with cash. It is like bandaging a broken arm, or giving a piece of meat to a hungry man. It does not end the poverty of the land claimants. It is therefore amiss of Thabo Mbeki to generalise about the difference between South Africans and Zimbabweans, without examining the underlying causes of this problem.

Xaba is a PhD student in the Sociology Department at Rhodes University and Roodt is a professor in the Department. Views expressed are not necessarily those of GroundUp.