Archive photo: Bernard Chiguvare

14 December 2016

A national minimum wage has been put on the table. But the proposals from the Deputy President’s National Minimum Wage Advisory Panel go well beyond recommending a R20 per hour wage level.

Although the proposed level – which amounts to R3,900 for a 45-hour workweek – sits well below the level of working poverty (R4,480 in October 2016), I have argued elsewhere that it could serve as a viable starting point, balancing the competing interests at play.

However, other aspects of the proposal significantly undermine the gains to workers and risk the national minimum wage having little effect in the coming years.

Central to the Report’s proposal is a two-year ‘transition period’ at the end of which the national minimum wage comes into full effect. A transition phase is a reasonable approach, but the devil is in the detail.

One of the most problematic proposals is that the level not be increased at all during the first two years – the R20 per level is ‘frozen’ until the end of June 2019. This means that the real value of the national minimum wage will fall. As the poor are hit by the highest levels of inflation – 8.9% in October 2016 – this represents a critical loss to already meagre incomes. Inequality will not be tamed as wages for higher-paid workers will still rise.

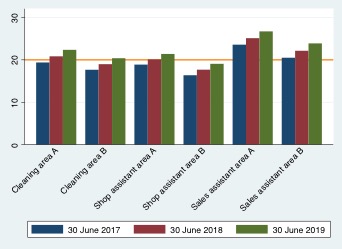

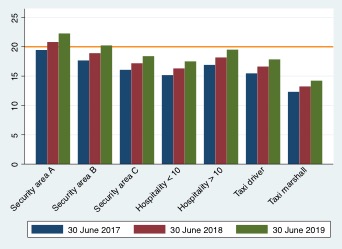

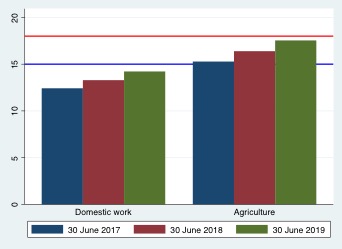

In order to assess whether the new system will benefit workers it is worthwhile to compare the R20 per hour level to the level the existing sectoral determinations will reach by 30 June 2019 should they continue to increase as they have over the past few years.

We see in the graphics that by 30 June 2019 the overwhelming majority of workers covered by sectoral determinations (which make up the bulk of low-wage workers) would already be earning at, above, or very close to R20 level.

Contract cleaning staff in metros would be earning R22.36, in non-metros R20.38. In wholesale and retail, general shop assistants and sales assistants would almost all be above R20 by 30 June 2019.

However, the wage freeze again dampens the benefits. By the end of the transition period the current system would set a minimum for domestic workers of R14.22, just below the R15 stipulated (75% of R20), while the agricultural wage floor, under the current system, would be at R17.54, just shy of the R18 mark (90% of R20). When brought in line with other sectors their wages would rise dramatically.

There are two counter arguments. First, one may argue that the gains may be eaten away by 2019 but the jump in 2017 from the existing level to the new national minimum wage is large and so workers will benefit significantly in 2017 and 2018. Second, many workers currently still get paid less than the legislated minimum wages in these sectors. One motivation for a national minimum wage is that it is easier to enforce and would significantly reduce such violations and hence improve workers’ pay.

However, another worrying proposal is that while businesses should pay the stipulated level during the transition period, the panel proposes that there are no sanctions for failing to do so – initially making the new national minimum wage essentially voluntary. During this period the level is to be popularised and businesses given a chance to adjust. Sanctions are proposed to kick in after two years for most businesses and three years for small businesses.

This grace period appears to be justified on the basis of giving time for businesses to adapt and the Department of Labour to strengthen the inspectorate. However, this lengthy period is in addition to the time between now and the enactment of the legislation, a time during which businesses can already start to plan and adapt.

A further anomaly is that the Report appears to indicate that the wage freeze is necessary so that evidence can be collected in order to assess the impact before increases are made. But how does one properly assess the impact when compliance is voluntary? And might this entrench a culture of non-compliance?

Speaking in Parliament, Deputy President Cyril Ramaphosa couched the ‘transition period’ as a strategy to mitigate job losses, which he asserted have occurred ‘everywhere’ that minimum wages have been implemented. This is contrary to his previous statements and is incorrect. The evidence is unequivocal – minimum wages have had, on aggregate, a very slight or neutral impact on employment, without such transition periods in place.

The Advisory Panel acknowledges this while deciding to adopt a ‘cautious’ approach, an understandable and appropriate decision.

However, the lengthy period of non-enforcement with no increase to the level goes well beyond caution. It is also unprecedented. Other countries have had periods between announcing the level and the enactment of the legislation, for instance Germany. And some have deferred the inclusion of certain sectors under the legislation, for instance in Malaysia where microenterprises (under five employees) were not included for the first six months. But it is exceptionally rare to enact the legislation but actively not enforce it for two years.

These elements risk undermining the gains that accrue from a national minimum wage of R20 per hour. The combination of the wage freeze and non-enforcement during the transition period means the new national minimum wage effectively only kicks in in 2019 when many sectoral determinations would have reached R20 per hour anyway.

Notes on graphs: Sectoral determination are increased as stipulated in regulation or in line with previous increases. Contract cleaning and hospitality are increased at CPI+1.5%, wholesale and retail area A at CPI+0.5%, wholesale and retail area B at CPI+2%, domestic work Area A at CPI+1% and Area B CPI+2%, security, taxi and agriculture at CPI+1%. CPI is taken from projections in the medium-term budget policy statement and is the average of inflation in the year of increase and the preceding year.

Views expressed are not necessarily GroundUp’s.