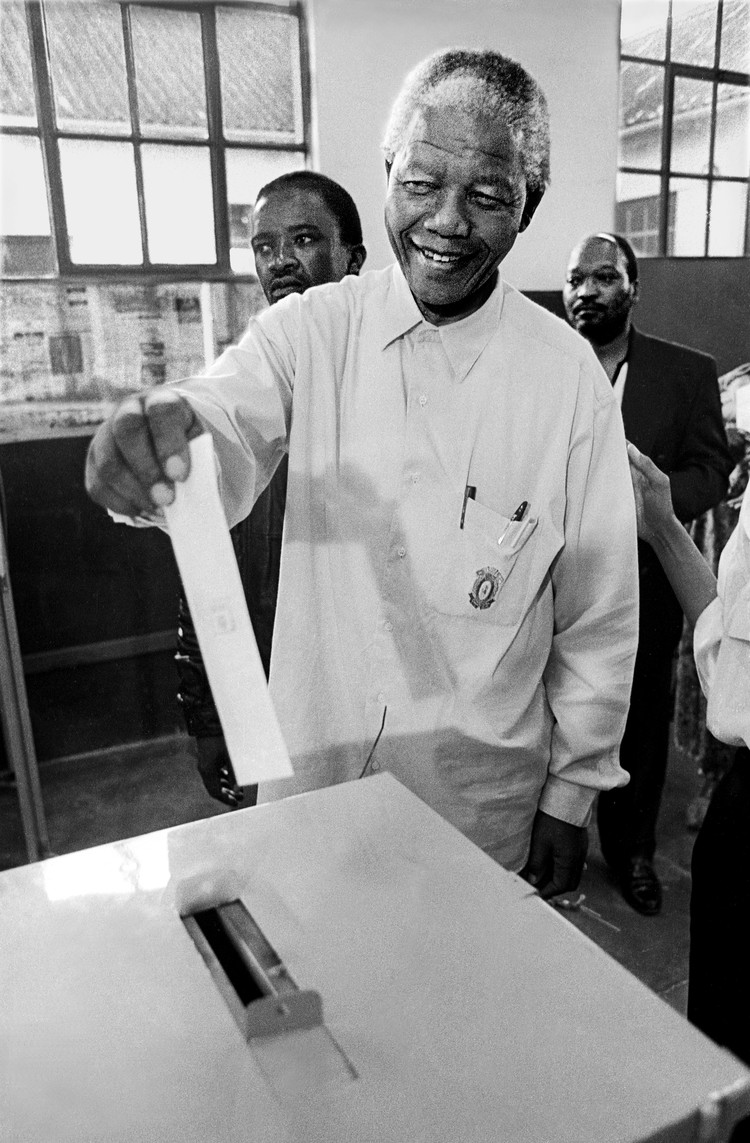

Nelson Mandela votes in South Africa’s first democratic election on 27 April 1994. Photo: Paul Weinberg. Reproduced with permission. (GroundUp does not have the copyright on this image and it is not published under our usual Creative Commons license.)

7 November 2018

Paul Weinberg, who shot the internationally recognised photo of Nelson Mandela voting in South Africa’s first democratic election, has demanded that the University of Cape Town (UCT) return his photo.

Weinberg sent a letter to the UCT Head of Special Collections Renate Meyer (published in full at the end of this article) airing his concerns. Weinberg said that his photo was removed from the foyer of the Special Collections in February 2018 without him being consulted as the photo’s owner, which he called “strange” and “disrespectful”. He claimed the photo was relocated to an “obscure” part of Special Collections “where it has sat without its caption for about six months”.

Weinberg speculated that the move had to do with the university’s former Vice Chancellor, Max Price, claiming that the Madiba photo and other pieces of art on display at UCT contributed to “institutional racism”.

Price’s July 2017 article stated: “Beyond any doubt, the photographers involved – Peter Magubane, David Goldblatt, Paul Weinberg, Omar Badsha – intended [their photographs] as ammunition in the struggle against apartheid. But if you are a black student born well after 1994 what you see is a parade of black people stripped of their dignity and whites exuding wealth and success. Even if you know the historic context of the photos, a powerful contemporary context may overwhelm this, leading you to conclude that the photos are just one more indication of how this university views black and white people.” This was under a subheading: “Institutional Racism”.

Weinberg wrote that Meyer had said the photo had been moved “due to the discussion with the campus community regarding perceptions of accessibility and African studies and due to recalibration efforts”.

The institution, Weinberg said, had “dismally failed to stand up for art and artists at UCT” and had “failed to defend their work and to take a stand on the burning of art and UCT’s own controversial censorship”.

For these reasons, he said, he felt it necessary to demand the photo be returned. “Given that this year is a celebration of Nelson Mandela’s 100 birthday, I would like to honour and pay tribute to his legacy and values appropriately.”

In a statement to GroundUp, UCT Communications Director Elijah Moholola said: “The artwork was moved as part of the constant and regular circulation of works of art around UCT’s campuses, which is carried out for a variety of reasons at different buildings. The artwork was relocated from the stairwell to a place within the Jagger Reading Room. UCT believes that wall where the artwork has been relocated is in fact more prominent than where it was previously placed.”

Following protests in 2016 when students burned an assortment of UCT-owned artworks, the Works of Art Committee (WOAC) removed works of art from public viewing “for safety reasons”.

Meyer told GroundUp that Weinberg had every right to demand the photo back because it was never donated to the university. But, she added that Weinberg’s letter had a “series of slippages”. She denied the claim that the photo was removed because of campus discussion and reiterated Moholola’s assertions that the movement of artworks was routine and that the photo might even have more prominence in the reading room.

Meyer added that UCT had been in a period of “transforming from an environment of demanding to one of listening and discussing” over the past few years. By demanding the photo be removed from the archive, Meyer said, Weinberg reduced the photo’s “potential for discussion.”

“Transformation takes a lot of work,” said Meyer. “We’re all responsible. Accusations can be harmful.”

Dear Renate

I request my photograph of Nelson Mandela voting for the first time in 1994, be returned to me. The photograph at first, was part of an installation in the foyer of the Special Collections assembled in 2013 and then removed a day before I returned to the Library, after a two year secondment at the CAS gallery, in February, 2018. When questioned about this you said it was “due to the discussion with campus community regarding perceptions of accessibility and African studies and due to recalibration efforts.” As the person who first worked with the WOAC and the Library to curate that space, the owner of the photograph (copyright, cost of print and frame are mine) I was never consulted and found the decision not only strange but also disrespectful. Madiba voting was then later relocated (‘recalibrated?’) to an obscure part of Special Collections, where it has sat without its caption for about six months.

Madiba voting in 1994 has had an unfortunate time at UCT. It was an image identified by the former Vice Chancellor of UCT in 2017, Dr Max Price along with images of other photographers – Peter Magubane, Omar Badsha, David Goldblatt and myself as “art on the walls” of UCT which included the sculpture by Willie Bester of Sarah Baartman that contributed to “institutional racism”. When pointed out that neither Omar Badsha or Peter Magubane had photographs on the walls of UCT and that the images of David Goldblatt and mine were all from a post apartheid period, Max Price wrote another article saying what he really meant was the digital photographic collections contributed to “institutional racism”. The seminal work of the Cordoned Heart (curated by Omar Badsha), Beyond the Barricades, Staffrider Exhibitions and other photographers whose work ranges in style and approach and content. This was a project I had devoted ten years of my life at UCT making valuable photographic collections accessible for our history, memory, and heritage. Out of these endeavours has emerged considerable research, publications, curated exhibitions and scholarship. That the “digital photographic archive” can even be considered an instrument of “institutional racism” by an institution that positions itself as one of the best in Africa, is somewhat mind boggling.

In the months I have now left the Library and UCT, I have had time to reflect on the events of the past period. This photograph was loaned by me to the WOAC and the Library at the time. I was quite prepared to donate it to the institution as I felt it was a significant part of our history. As a photographer and in in this instance the artist, one only really speaks through one’s work. Given that this year is a celebration of Nelson Mandela’s 100 birthday, I would like to honour and pay tribute to his legacy and values appropriately.

I found the manner in which the photographers were accused of contributing to “institutional racism” totally unacceptable, the very poor way the institution (including the Library) has failed to defend their work and to take a stand on the burning of art and UCT’s own controversial censorship an anathema to all I stand for. The institution has dismally failed to stand up for art and artists at UCT, ‘the digital photographic archive’, freedom of speech and the values enshrined in our constitution which undergird the very existence of our democracy, and the tenets of academic freedom. For the record here is what stands in our constitution, “(1) Everyone has the right to freedom of expression, which includes— (a) freedom of the press and other media; (b) freedom to receive or impart information or ideas; (c) freedom of artistic creativity; and (d) academic freedom and freedom of scientific research. (2) The right in subsection (1) does not extend to— (a) propaganda for war; (b) incitement of imminent violence; or (c) advocacy of hatred that is based on race, ethnicity, gender or religion, and that constitutes incitement to cause harm.”

That we are a country with a contested history is very evident for all who have lived here, pre and post Apartheid. Engaging with it is necessary and integrally part of our ongoing journey for a more vibrant democracy and for a better society and world. Here is what the highly respected organisation PEN says about art which was as relevant during the apartheid days, as it is today, “In all circumstances, and particularly in time of war, works of art, the patrimony of humanity at large, should be left untouched by national or political passion.”

I have reviewed and now revoked my initial gesture to make a donation to the institution. Please return my image to me and I will find a new home for Madiba voting for the first time in 1994.

Regards

Paul