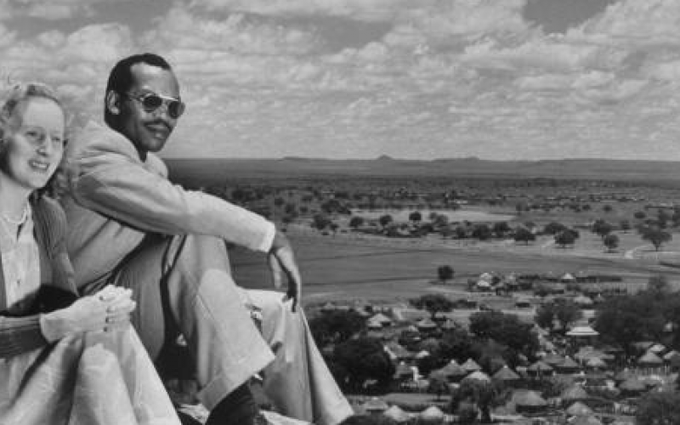

Ruth and Seretse Khama. Seretse was the first president of Botswana.

Photo: Lady Khama Charitable Trust (copied as fair use)

30 September 2016

Fifty years ago today the independent Republic of Botswana came into being. At midnight, 29 September 1966, in the teeth of a vicious Kalahari sandstorm, the Union Jack, which had flown over the land for 81 years, was lowered to the sounds of God Save the Queen, in a stadium filled with 5,000 people in the new capital, Gaborone.

It might never have been had Rhodes, Malan, Strijdom and Verwoerd had their ways. The Bechuanaland Protectorate was supposedly a British buffer against Boer and settler expansion, but Rhodes called for it to be transferred to South Africa as early as 1894.

Khama III, one of the leading diKgosi, visited Britain in 1895 to rally public opinion against this possibility. He said, “We think the Chartered Company will take our lands, that they might enslave us to work in their mines.”

The campaign to get hold of Bechuanaland continued for decades. The first three Apartheid prime ministers all pushed for it to be incorporated into the Union of South Africa; in their mind it was the ur-Bantustan, a vast reserve that predated and surpassed the 7% of South Africa allocated to Africans in the 1913 Native Land Act (extended to 13% in the 1936 the Native and Land Trust Act.)

The 1954 Tomlinson Report, which held that the ‘native reserves’ within South Africa’s own borders lacked viability, referred to Bechuanaland, Basutoland and Swaziland as ‘heartlands’ for the Bantu Areas. This threat was real enough that the drafters of the Freedom Charter saw fit to include a clause stating, “The people of the Protectorates – Basutoland, Bechuanaland and Swaziland – shall be free to decide for themselves their own future.”

At the date of its independence the UN listed Botswana as one of the world’s ten poorest countries and the least developed in Africa. Two out of every three active male wage labourers were in South Africa at any given time, working in the mines and on farms. There were fewer than 30 university graduates among the black population. As the dust blew into the independence ceremony, the country was experiencing one of its worst ever droughts, with the national herd estimated to have been reduced by a third.

Reporting on the independence celebrations, The Times of London was pessimistic, even cynical: “Its problems are so great that its debut in the international world amounts to a striking act of faith that untrammelled self-rule is the supreme good.”

Today Botswana has a life expectancy of 63 for men and 68 for women. This is better than South Africa and a lot better than Zimbabwe. It has lower neonatal mortality than Zimbabwe, although is still behind South Africa in this regard. Adult literacy is 83% and overall enrolment in primary school, which is offered free by the government, is around 90%. Botswana has edged South Africa, Namibia and Mozambique in a cross-country study of primary school reading and mathematics. Its GDP is larger than Zimbabwe’s although Botswana has less than 20% of the population.

I know little about Botswana, and I have no doubt that the society shares the features of class rule and exploitation seen everywhere in the world, with a state capable of the violence needed to enforce these. In recent years voices have been raised about intrusions into media freedom and against the enlargement of a shadowy and allegedly murderous intelligence service. I don’t mean to minimise the struggle of workers, the unemployed, activists and students in Botswana today, or to exaggerate the country’s triumph over adversity. The San in particular have faced on-going dispossession and discrimination. Looking back to independence 50 years ago what I really want to recall is a love story, one of the most remarkable of the 20th century, that between Seretse and Ruth Khama.

“All marriage is an experiment,” Ruth once admitted. “I’m not starry-eyed about this,” she said on another occasion. “I’ll admit right here that these past seven years have been difficult ones.” But this partnership withstood the full machinery of the British Empire’s every effort to destroy it, and in the end many of its fiercest opponents would admire the couple grudgingly.

The campaign to prevent and then to punish this love, by the British authorities, urged on by the racist regimes in Rhodesia and South Africa, is one of the most ignoble in the bulging annals of colonial duplicity. Perfidious Albion has never been more naked. This story has been painstakingly researched and documented by Susan Williams in her book Colour Bar: The Triumph of Seretse Khama and his Nation, which I draw on heavily here.

Seretse Khama became the first President of Botswana 50 years ago today. But he was born the heir to the Bamangwato chieftancy, the most powerful of the eight Tswana chieftancies recognised by the British colonial authorities. Seretse went from Wits to Oxford where he met and fell in love with a white woman, Ruth Williams. They courted for over a year and arranged to marry in October 1948, less than six months after Apartheid became official policy in South Africa.

Jomo Kenyatta had married Edna Grace Clarke, the second of his four wives, in 1942, but this was different. Here was the future King of the Bamangwato, a border people, whose labour was interwoven with South African capitalism, whose capital was at Mafikeng, within South Africa, presuming to transgress the most basic prejudices of the racial order.

The rush of correspondence to stop this abominable wedding was intense. The British government hired lawyers, mobilised diplomats and succeeded in getting a Church of England Bishop to refuse the marriage. Seretse’s uncle forbade him to proceed and Ruth was cast out of her family for a while. The couple eventually succeeded only by slipping undetected into a Registry Office where they were married without fanfare early one morning in front of three witnesses.

The Bamangwato, who were then governed by Seretse’s uncle Tshekedi as Regent, held three kgotla to debate Seretse’s decision to take a white wife. By the end the thousands of assembled men had decided almost unanimously that they would support the marriage and would not be denied their rightful leader because others objected to his choice.

Only Tshekedi and his supporters refused to countenance the match. This gave the colonial authorities the pretext they needed: they would refuse Seretse’s installation as Kgosi on the grounds that it would cause divisions in the Bamangwato.

Sir Walter Harragin, the Chief Justice of the High Commission Territories (Bechuanaland, Basutoland and Swaziland) was sent to conduct an inquiry. He pronounced Seretse a fit and proper person to be Kgosi, noting the support he had from the people, but recommended against it on the grounds that it would offend the white governments of South Africa and Rhodesia. The British suppressed this report, which they deemed to have come to the “right conclusion for the wrong reasons”, in other words to have been too honest about the real reason. As has been observed by historians, if African nationalism was on the march in the 1950s, so too was white power.

Uranium had been discovered in South Africa, which the British wanted for nuclear weapons amidst the emergent Cold War. Churchill, who had lost power to Labour after the Second World War, initially took a principled stand, calling the treatment of Seretse and Ruth a “disreputable transaction”. He said: “I believe firmly in 2 principles: (1) Christian marriage, & (2) the bond of strong animal passion between husband & wife. Both exist in this case.”

But Jan Smuts intervened and changed Churchill’s mind, convincing him that support for Seretse would only harden the Nationalists who had defeated Smuts in South Africa. “Natives traditionally believe in authority,” Smuts explained, “and our whole Native system will collapse if weakness is shown in this regard.” After that, including upon his return to power in Britain, Churchill did nothing to return Seretse to his life. This capitulation to racism was the norm in white society. Quintin Whyte, the Director of the South African Institute of Race Relations, said that although the Institute opposed the Mixed Marriages Act on principle, it did not approve of mixed marriages, and that support from liberals would go to Tshekedi.

What ultimately resulted was a five-year banishment. Seretse was not even permitted to live in his own country as a private citizen. Instead the colonial authorities decided to administer the tribe directly, farcically asserting that removing the man a 9,000-strong kgotla had chosen to lead them would give the Bamangwato “a more democratic say” in their own affairs.

The Tswana diKgosi upheld a feudal patriarchy, albeit with exceptions like Mrs Moremi, the Regent of the Batawana. Despite this, nobody was in any doubt about the people’s choice, not least the colonial authorities, as their private correspondences have revealed. At one point, in an apparently unprecedented event, a few thousand women stormed the male-only kgotla to voice their protest directly to a colonial official.

There are many villains in this story, but perhaps none surpassing Sir Evelyn Baring. This colonial manager ended his career as Governor of Kenya where he instituted a state of emergency in 1952, in an attempt to crush the liberation movement known as the Mau Mau uprising. 20,000 freedom fighters were killed, 150,000 Kikuyu were interned in concentration camps in which food deprivation and torture were rife, and 1,090 were sent to the gallows. 32 white settlers died. Prior to this, as High Commissioner for Southern Africa, Baring had responsibility for Bechuanaland.

In a letter to his wife he described his relationship with Malan, the founder of Apartheid, as “practically blood brothers”. He had never met Seretse or Ruth in his life but decided to deliver the news that Seretse would not be returning as Kgosi in person at the kgotla grounds in Serowe. Baring was resplendent, like an albino peacock, in white uniform and sword, tall cocked hat and white feathers, with the Star of St Michael and St George on his chest. But the people boycotted his kgotla. Instead of thousands he faced an empty scene. This was one instance in a long campaign of passive resistance. “Never before in British Africa,” wrote one correspondent, “had the Crown’s representative been so insulted.” Baring never forgave the Bamangwato, and participated in every step of their subjugation.

But eventually the tide turned for a number of reasons. Decolonisation was sweeping down the African continent as European powers decided that direct rule had become less integral to economic exploitation. Simultaneously, a powerful campaigning movement was built in London. This took the form of a “Seretse Khama Fighting Committee”, which ultimately merged with similar organisations for a final assault on British colonialism across the globe. A young Tony Benn played a leading role, and he and the Khamas grew close. Seretse was made godfather to Benn’s daughter and Seretse and Ruth named a child after Benn.

The movement in London was boosted by a visit from Seretse’s supporters. “Black as we are,” they said, “we can think. Government is doing something unjust to us.” And by forcing the Khamas to live in the UK the colonial authorities scored an own goal, placing a powerful leader and rallying point in their midst.

Seretse toured the country, his following growing as consciousness against racism grew: “Don’t let your Government teach us racial prejudice. We don’t have it. We don’t want it.” At the same time awareness of the evil of apartheid was becoming widespread. Here was someone, a man of gravitas and intellect, who wanted to build a different society next door to racist South Africa.

Perhaps what tipped the scales was the discovery of minerals on Bamangwato land, which according to the legislation establishing the protectorates could not be exploited without Bamangwato consent. This, the people refused to give without Seretse’s involvement. These were not yet the massive diamond deposits that would make Botswana the world’s leading producer — those were thankfully only revealed post-independence — but were significant enough to give Seretse, finally, a bargaining chip he could play.

A deal was struck in 1956 whereby Seretse could return, but not as Kgosi. He had to repudiate any claim to the chieftaincy. He had in fact been offering this for years, and publicly embraced it: “Democratic development is much better than being a chief,” he said. He sat as deputy chair of the governing council. He also reconciled with his autocratic uncle Tshekedi, a figure that many of the Bamangwato had turned sharply against, but someone who retained powerful friends in Britain.

Seretse’s return to Serowe evokes images of Mandela’s release from prison 34 years later. There was joy unconfined and celebrations for days. There was outrage in South Africa but it was no longer decisive. Both the Rhodesian Herald and Die Transvaler newspaper of the ruling Nationalist Party said that southern Africa would now be contaminated with ‘chocolate babies’. One of these, Ian Khama, is President of Botswana today.

This hysteria about “racial mixing”, and fear that the example of Seretse and Ruth would lead to a crumbling of the fiercely policed racial hierarchy, was central to the entire shameful ordeal. A leading Rhodesian politician said that it would lead to “nothing but misery, confusion and degradation”. He insisted that his racism was not malicious but benevolent: “If we are proud of our purity, so is the native… I feel confident that by this resolution we are doing the Bamangwato tribe a great and invaluable service.”

In salient contrast was the embrace of Ruth by the Bamangwato, especially the women. While the whites of Serowe generally boycotted Ruth, she was welcomed as a member of the community, and lived out her life in Botswana long after Seretse’s eventual death. Lilian Ngoyi too had visited the Khamas in London and developed a strong friendship with Ruth. “Seretse and I are one race. Colour doesn’t enter into it,” Ruth said. She spoke warmly of him as a husband and father to their children and admired his consistent gentleness and humour throughout the years of harassment and exile.

It is hard to imagine quite the extent to which this drama was a global news sensation at the time. Miriam Makeba had a hit with “Pula Kgosi Seretse” and for the world’s press, especially the British paparazzi, this story of an African prince and a British “typist” (as they wrongly described her) was the Kim and Kanye of its day. Tabloid photographers camped outside their windows, hoping for a photograph of the couple in bed. What the press uncovered less of was the lies of the colonial officials, who denied the role of pressure from South Africa, suppressed reports and misrepresented discussions with Seretse. Eventually, though, some journalists grew to respect the pair and wrote moving portraits that helped to shape opinion in their favour.

It is interesting how little recognised Seretse is today. Botswana is a country with a small population and it did not organise a revolution or fight a war of liberation. Seretse left us little in the way of political rhetoric. One memorable statement, made a few years prior to full independence was this: “We should get on and have no fear that we may incur someone’s displeasure, as long as what we do is internationally accepted… And if we are right I am afraid emotion must come into this; we should not bother very much with what anyone might say … We have ample opportunity in this country to teach people how human beings can live together.”

He was elected Botswana’s first President in a landslide and began the task of constructing one of the most deliberately underdeveloped countries in the world. When Mandela addressed the Organisation of African Unity in 1994 he ranked Seretse alongside Nkrumah, Lumumba, Cabral, Machel and Luthuli.

At a time like ours, when radicalism is performed and revolutionary politics is often devoid of revolutionary content, the life of Seretse Khama deserves a moment’s reflection. The private has seldom become so intensely political. His response was soft-spoken but steadfast, a brand of leadership that brought material progress within the confines of the global order and a measure of defeat for racism.

South Africa may have stopped trying to annex or incorporate Botswana but our multinationals have made Africa their commercial hinterland. Profits cross borders fairly freely but human beings have greater difficulty. Having achieved independence, new thinking on regional cooperation and gradual integration is now needed. Looking back and looking forward, 50 years from that dusty night in Gaborone, a night which ended in life-giving rain, it feels like a good time to say Pula! Pula Botswana.

Follow Doron Isaacs on @doronisaacs.