Diastella buekii, a critically endangered protea, is threatened with extinction due to aquifer drilling at Wemmershoek. Photo: Ross Turner

28 February 2018

The author, who is an ecologist, argues

water extraction from the Table Mountain Group Aquifer (TMGA) could have serious consequences for biodiversity and threaten future water security;

in their rush to increase the water supply, local municipalities have been violating environmental management legislation, compromising the catchments on which we rely in favour of a relatively small water source that will not come online in time or in quantities to make any difference to Day Zero; and

alternative options like clearing of alien vegetation would provide far more water.

The rush to extract underground water to overcome the drought may be putting Cape Town’s future water supply in danger.

Hasty schemes by the City of Cape Town and the Stellenbosch and Drakenstein municipalities to extract water from the Table Mountain Group Aquifer (TMGA) could have dire consequences for biodiversity and the environment. Extracting water from the aquifer will make no difference to Day Zero, but it might well compromise the catchment area and its ability to supply us with water in future.

The existing Western Cape Water Supply System — the dams and pipelines that have supplied our bulk water to date — is, and will likely always be, our biggest source of bulk water, dwarfing all the augmentation schemes combined. This system is dependent on runoff of high quality water from healthy catchments and streams and it is imperative that we manage them in a sound manner.

Unfortunately, local municipalities have panicked and are hastily drilling boreholes and developing roads, pipelines and power lines in environmentally sensitive areas, often violating environmental management legislation. This is threatening critically endangered species with extinction, degrading threatened ecosystems and wetlands, and drastically altering the hydrology of catchments on which our survival depends.

Impacts that we know of include the City of Cape Town’s drilling at Steenbras Nature Reserve), Stellenbosch Municipality pouring mud and sludge into the Eerste River at Jonkershoek Nature Reserve, and the Stellenbosch Municipality putting boreholes and ditches through critical wetlands that support multiple species that occur only at these sites and nowhere else in the world at Wemmershoek.

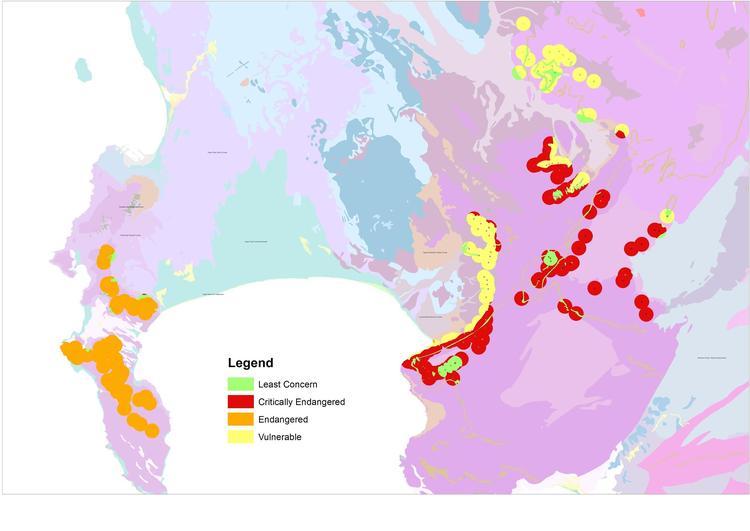

These are just the beginning. Much more is planned for the Table Mountain Group Aquifer by the City of Cape Town alone (see map below) with risks to biodiversity and water supply from our catchments, and to the nature reserves and Table Mountain National Park.

The City of Cape Town’s bulk water augmentation schemes have been granted exemption from the regulations of the National Environmental Management Act (NEMA) by the provincial Department of Environmental Affairs and Development Planning, since the current water crisis constitutes an emergency under Section 30A of the Act. But this exemption is not a licence to kill and the City still bears the responsibility to adhere to Section 2 of the Act and minimise impact on the environment.

Section 28 also applies: “Every person who causes, has caused or may cause significant pollution or degradation of the environment must take reasonable measures to prevent such pollution or degradation from occurring, continuing or recurring, or, in so far as such harm to the environment is authorised by law or cannot reasonably be avoided or stopped, to minimise and rectify such pollution or degradation of the environment.”

Mounting evidence suggests that there has been little adherence to these regulations. Drilling contractors are operating without environmental management plans, without site inspections for sensitive species, and without environmental control officers on site. These are all actionable offences under the Act, liable to a fine not exceeding R10 million or imprisonment for a period not exceeding ten years, or both.

A quick scan reveals that almost every one of the 222 drill points (that we know of) planned by the City of Cape Town falls within ecosystems listed as threatened under NEMA. Of these, 141 fall within formal protected areas.

None fall within areas where most of the diversity has already been eradicated. Yet the drill sites could easily have been be selected to minimise biodiversity loss.

Altogether, 5,652 populations of 266 species of concern for conservation are threatened on the proposed sites, including every single known population for nine of these species. If implemented, this plan has a good chance of having one of the biggest biodiversity impacts of any development anywhere in the world.

But it doesn’t stop there.

Many of the drill sites target water from shallow unconfined aquifers. These are not the kilometres-deep limitless supplies of “fossil water” that you may have heard of, which are supposedly (there is some disagreement in the scientific literature about this) not connected to our surface waters. Unconfined aquifers are directly linked to the water table and surface waters, although the links are complicated and uncertain. So any additional removal of water through these boreholes will reduce runoff to our streams and dams.

In short, this is taking the very same water that replenishes our water supply system, feeds groundwater, supports biodiversity in the catchments and supplies the rivers that feed towns and farm dams. Extracting this water is cancelling the insurance policy we need since rainfall is predicted to become ever less certain.

In the near future, the damage from infrastructure developments and the drawdown from the water table are likely to promote soil erosion and invasion by disturbance-loving woody alien plants like pines and wattles. Erosion will fill our dams with sediment, reducing their storage capacity.

Alien species have already invaded extensive areas of our catchments and experts estimate they currently reduce runoff into our dams by more than the 80 million litres per day (at most) the City hopes to derive from the Table Mountain Group Aquifer. If left uncontrolled, they are expected to use four and a half times the City’s estimated yield from the aquifer by 2045. Their spread will not only threaten whatever biodiversity remains, but will further reduce runoff and recharge into our dams and aquifers.

The lack of investment in clearing alien species is an opportunity lost in the response to this drought. The focus on engineering solutions as opposed to ecosystem-based approaches is disappointing. Stemming the invasion of our catchments by alien vegetation has been a national priority since 1995, based on good evidence. While the Working for Water programme has made a huge difference at the national scale, competing objectives and lack of funds and/or coordination have hampered this goal and the threat to our ecosystems and water resources grows by the day. Investing in alien clearing could alleviate some of the drought-related job losses, and make headway against a threat that we cannot continue to ignore.

We should not sacrifice good environmental management for the sake of expediency. Quick and dirty solutions for today’s challenges will be paid for by future generations.

Views expressed are not necessarily GroundUp’s.