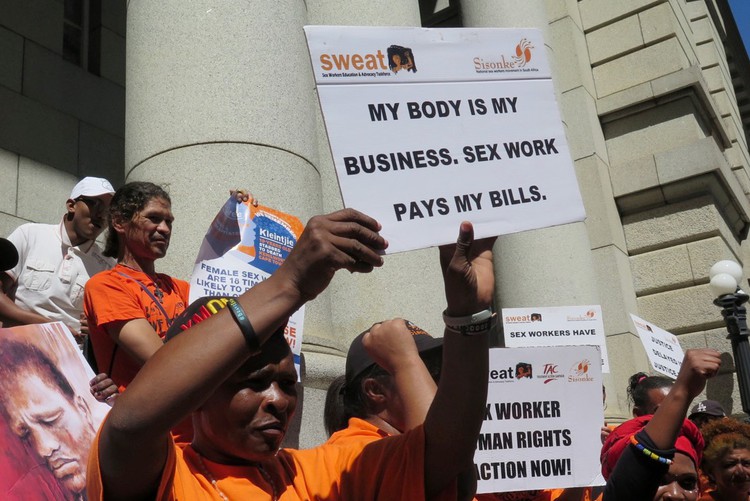

Sex work activists protest outside the Western Cape High Court in 2017 at the trial of of artist Zwelethu Mthethwa. Mthethwa was sentenced to 18 years in prison for murdering a sex worker. Archive photo: Ashleigh Furlong

4 February 2019

Gavin Jacobs started his career in sex work in London. Running out of cash, he learnt about massage parlours though friends. Not wanting to return to Cape Town, his hometown, just yet, he decided to work at one.

Gay, young and energetic, Jacobs partied hard and often. So he thought, “I might as well get paid for it.” He was 21 when he was paid for sex for the first time. His client was a little younger than him.

Around 2002, Jacobs returned to Cape Town and worked in restaurants. Needing more money, he started working at “massage parlours” in Sea Point. Now 47, Jacobs says that he hasn’t had a client for ages, but would consider it “if the opportunity comes along and the money is right”.

Sex work is illegal in South Africa. The closest that came to changing was in a highly publicised court case two decades ago. In 1996, a policeman went to a brothel in Pretoria, and paid R250 for a pelvic massage. The brothel owner, Ellen Jordan, and two of her employees, Louisa Broodryk and Christine Jacobs, were arrested.

The three women were found guilty of brothel-keeping and providing sex for reward. They appealed to the Pretoria High Court, which found the sex-for-reward provision of the Sexual Offences Act unconstitutional, but upheld the magistrate’s guilty verdict on brothel-keeping.

The case went to the Constitutional Court which, in 2002, upheld both guilty verdicts by the magistrate. The brothel-keeping verdict was unanimous, but the sex-for-reward one was a split 6-5 decision. It was a big blow for sex worker rights organisations, especially activist organisation SWEAT, who put a lot of time and energy into the Jordan case.

Jordan herself was only fined R600 by the magistrate, but standing up for what she believed in cost her over R3 million in legal fees according to a newspaper report at the time.

No sex-work case has been back in the country’s highest court since then.

Not all male sex workers are gay; some are straight, others bisexual. But men are the clients of most male sex workers. A 2013 study by SWEAT estimated that there are 138,000 women, 7,000 men, and 6,000 transgender sex workers in the country.

Jacobs says that it is not only about sex. “Sometimes it’s just about going to dinner with somebody”, “or just going somewhere with them”. Sometimes, clients are “just looking for someone to talk to,” he says.

Gavin Jacobs started doing sex work in London, and then continued doing it when he returned to South Africa in 2002. Photo: Ashraf Hendricks

Prices for sex work vary dramatically. Online you can pay as low as R250, but higher end escorts can charge R1,500 or more. Jacobs says that on the high-end scale, you could pay at least R1,000 just for an escort to accompany you to dinner.

For Jacobs sex work was a completely uncoerced option. But he points out that some men have no good options: “There’s a lot of people who do it because they feed their families and pay their kids’ school fees,” he says. Sometimes it’s substance abuse. “They have to smoke so they have to find a way to make money.” They can’t find a mainstream job “and nobody’s going to employ them because of stigma,” he says.

In contrast to women sex workers, it is uncommon to find male sex workers on the streets. Most of the male brothels have closed down so sex workers advertise their services online. “They have their own websites. They’re working in their own space,” says Logan (name changed), a member of Sisonke, a movement of sex workers.

Originally from Zimbabwe, Logan did sex work because he was unable to get a South African work permit. Today he mostly focuses on advocacy. “I’ve become the voice of the voiceless,” he says.

Stigma makes it very difficult to become a sex worker. “I’m shaming my community, even my family,” says Logan. But in the end “It’s like any other type of work”, but because it’s illegal “People don’t see it as work,” he says.

Ending the prohibition on prostitution in the Sexual Offences Act is the main goal of sex worker rights activists. “Sex workers suffer huge amounts of stigma as it is, and criminalisation reinforces this,” says Professor Francois Venter, a doctor based at WITS university’s Reproductive Health Institute. Venter explains that criminalisation makes it difficult for workers to get police protection and health care services. “They are imprisoned arbitrarily, blackmailed, robbed and assaulted by police officers,” says Venter.

Criminalisation makes it difficult for sex workers to remain sexually healthy. Decriminalisation would allow “full access to health and social care” and “non-judgemental services” says Venter. It will make it easier to get sex workers services to prevent and treat HIV, for example.

Logan used to do sex work. Now he says he tries to be the “voice of the voiceless”. Photo: Ashraf Hendricks

But things may be changing. Support for decriminalisation is growing. The prestigious medical journal The Lancet has published several articles advocating decriminalisation. The Southern African HIV Clinicians Society, the biggest organisation of doctors treating HIV in the country, also supports decriminalisation.

Committees in Parliament have also been discussing and supporting the call for decriminalisation, says Lesego Tlhwale of SWEAT. And last year, Deputy Police Minister Bongani Mkhongi called for decriminalisation, saying police didn’t want to arrest sex workers but had to because of the law.

But support for full decriminalisation is by no means unanimous. In 2017, a report by the South African Law Reform Commission (SALRC) on adult prostitution recommended partial decriminalisation: only a person buying sex would be acting illegally. This position is supported by Embrace Dignity, an organisation campaigning to end prostitution, but opposed by sex worker rights groups.

“SWEAT & Sisonke are working hard to reverse the recommendation by SALRC,” says Tlhwale.

Full decriminalisation of sex work will probably come too late for Jacobs, Logan and their clients, but for future generations of sex workers decriminalisation may make their work safer, healthier and more acceptable in society.