17 August 2021

The mother of a dead child has given Viewfinder access to the record of the disciplinary hearing of the police officer accused of killing her son. The officer was found not guilty, though the police watchdog had concluded he had a case of “murder” and “misconduct” to answer. The tapes reveal the inner workings of South African Police Service hearings, from which even the police watchdog is excluded.

When Lieutenant Michael Thebus appeared before a police disciplinary tribunal, accused of shooting a teenage boy in the back, there were only three other people in the room: two fellow police officers and Thebus’s union representative. The boy’s mother, Klarina Reed, waited in the foyer outside. Viewfinder reports.

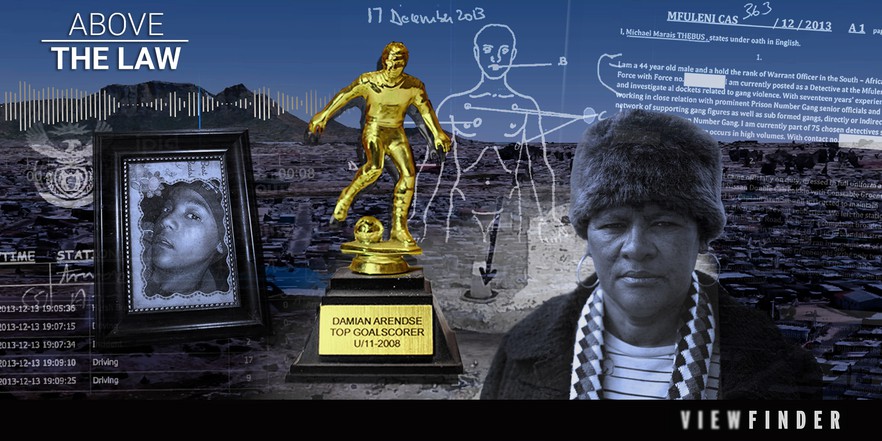

For SAPS the hearing was a legal requirement. The police watchdog — the Independent Police Investigative Directorate (IPID) — had found that Thebus had a case of “murder” and of “misconduct” to answer for in the killing of 15-year-old Damian Ahrendse in Wesbank, on the Cape Flats, a little under a year earlier.

It was the morning of 1 December 2014. As the hearing got underway inside a police station conference room at Melkbosstrand, north of Cape Town, the chairperson hit “record” on a voice recorder.

Those present introduced themselves: the chairperson Lieutenant Colonel Romburgh, Lieutenant Thebus, SAPS’s representative Captain Gerhard van den Bergh and the South African Policing Union’s Willem Coetzee.

The full recording of Lieutenant Michael Thebus’ disciplinary hearing, as received from SAPS following a public records request by Damian Ahrendse’s mother, Klarina Reed.

Van den Bergh was the evidence leader, a role similar to a prosecutor in a trial. His job was to “charge” Thebus and to “lead evidence” on the conduct which gave rise to the hearing.

“We’ll put this thing through the process, and no one can point a finger afterwards,” he said during the opening phases of the hearing.

He then called a witness — Damian’s half-brother, Dominique van Wyk — who said that he had seen Thebus shoot at Damian. He called two police officers (Thebus’s partner Constable Adriaan Groenewald and his supervisor Captain JP Arendse) who testified to Thebus’s innocence. Finally, he called Thebus, the accused, to take the stand.

“As I have said, be calm. This is informal. You have seen that this is informal. The chairperson is not aggressive. The ER [employer representative] is not aggressive. Take a deep breath and tell us calmly your version of what transpired,” Van den Bergh said.

Lieutenant Michael Thebus, the police officer accused of shooting and killing 15-year-old Damian Ahrendse on 13 December 2013. Photo: SAPS

Thebus maintained that the person on whom he had fired was an armed suspect who threatened his life. He was “convinced” that it was not Damian.

On the second day, at about four hours into the hearing, Van den Bergh gave his closing statement. He said that Thebus’s version was accepted by his employer, SAPS.

“The employee, Lieutenant Thebus is thus found ‘not guilty’ of misconduct as charged,” Romburgh read as his verdict.

There was a loud exhalation.

“Thank you very much. No one would like to add anything?” Romburgh asked.

“No,” someone — unclear exactly who — said curtly over what was likely the sound of shuffling chairs and papers. Then, the recording ended.

Apart from criminal prosecutions in court, police accountability for even the most serious offences – murders, torture, severe assaults and rapes by on-duty officers – depends on the integrity of SAPS disciplinary proceedings.

A recent Viewfinder investigation revealed that police officers almost always emerge from these proceedings unpunished. The investigation also exposed the loopholes and conflicts of interest built into SAPS discipline management. Soon after these findings were published, police commissioner General Khehla Sitole admitted to Parliament that police discipline management needed to be overhauled.

Police disciplinary hearings take place behind closed doors and are exempt from external oversight. Outcomes are often reported back to IPID without any explanation. Watchdog officials quoted in our investigation inferred, from their own experiences, that senior police officers in charge of discipline management exploited a series of loopholes to protect colleagues implicated in violent crimes from consequences for their actions.

Since Damian’s death, Klarina Reed has asked IPID and other government departments for answers about her son’s killing and about the lack of consequences for the police officer whom she believes was responsible.

Damian Ahrendse. Photo: Anton Scholtz

“There’s no real answer that they can give me. I’m coming back with empty hands, empty promises. Then I think, ‘Okay there will be another day for me’. And if I’ve got a taxi fare, then I’ll pick up these files again,” she said, with reference to her bundle of documents on the case.

Last year, Reed submitted a public records request to obtain the recordings of Michael Thebus’ disciplinary hearing.

On the one year anniversary of Damian’s death, days after Thebus was acquitted, Klarina Reed was back on the pavement outside her house on Etona Street in Wesbank. She had just finished serving potjiekos to a group of her dead son’s teenage friends. On an open field nearby, they played soccer in memory of Damian. On the sidewalk next to where Reed stood was the spot where her son had fallen one year earlier.

Klarina Reed, Damian Ahrendse’s mother, outside her home in Wesbank. Photo: Anton Scholtz

On that evening, Friday 13 December 2013, Damian had stumbled around the corner and limped in the direction of his mother’s house, clutching his chest. A trickle of blood ran from his nose. A trail of blood lay splattered on the asphalt behind him, she recalls.

“I ran down to my brother Damian and asked him what was going on,” Donnecia Ahrendse, who was 19 at the time, said in her statement to investigators.

“Damian told me he had been shot. I asked him by who, and he told me by police.”

As Damian lay dying, a black double-cab Nissan bakkie with police insignia pulled up. Constable Adriaan Groenewald and Warrant Officer Michael Thebus, both detectives attached to Mfuleni Police Station, got out.

Dominique Van Wyk, Damian’s half-brother and a prominent member of the 26 Numbers gang, came running down the street.

“You shot my brother,” he said to Thebus, according to his statement.

Dominique van Wyk, Damian Ahrendse’s brother. Photo: Anton Scholtz

The police officers looked at Damian. Groenewald instructed a bystander to put pressure on his wound. The pair then got back into the bakkie and drove away. In their statements later that evening, they explained that they radioed for an ambulance and went to search for the “suspects” they believed to have shot Damian.

The bullet that had ripped through Damian’s torso had perforated both his lungs. Neighbours lifted him into the back of a grey Corsa bakkie, where a young man named Rothrickus Lewis held him as they were driven to Delft Community Health Clinic. But it was too late. Lewis said in his statement that Damian was no longer breathing when he handed the boy’s slight frame to clinic staff. Damian was certified “dead on arrival” at 7.30pm, about 23 minutes after he had collapsed on Etona Street.

Later, the nurses allowed Reed into the room where her son’s body lay. She and her daughter Donnecia stayed all night. At 6.26am an officer from the Western Cape Government’s Forensic Pathology Services came to collect the body.

When triangulated with witness statements, police vehicle movement records show that Michael Thebus fired his pistol somewhere between 7:05:35 pm and about 7:07:15 pm on the evening of 13 December 2013. During IPID’s investigation, two versions emerged of what happened in those 100 seconds.

According to Thebus and his partner Constable Groenewald’s statements, they were driving their in police bakkie pursuit of two armed “suspects” who had been involved in a shoot-out with police moments earlier. The police officers chased these gunmen onto an open field off Armada Street in Wesbank. Their bakkie got stuck in the sand. As Thebus got out, one of the fleeing suspects turned and pointed a gun at him and his partner. Thebus fired a single “warning shot” at the “suspect” who then turned and continued running out of sight. Thebus and his partner reasoned that this suspect may have been responsible for shooting Damian. Neither speculated that Damian and the “suspect” were the same person. Both were “under the impression” that Damian had been shot by the “suspects” that they had been chasing. A police shooting report would later concur that Thebus fired only one round of ammunition.

According to at least three other witnesses on the scene, a police officer shot at Damian Ahrendse and his friend Andrew Konna. Konna’s statement suggested that the pair had inadvertently been caught up in the heat of the officers’ pursuit of a suspect from an earlier shooting. Damian and Konna had started running as the police bakkie came charging across the open field in their direction. Konna said that an occupant of the bakkie fired several shots in their direction, not just one. Dominique van Wyk and Wesbank resident Shannon Pearce, who was 17 at the time of the shooting, said they also witnessed police shooting at Damian. Though Pearce’s name was known to investigators, her statement was not taken at the time. Viewfinder traced and interviewed her last year.

In her statement to investigators, Damian’s sister Donnecia Ahrendse said her dying brother had told her that “the police” had shot him after he collapsed on Etona Street. In fact, she said that Damian had identified Thebus as the shooter and later explained that Damian was familiar with Thebus.

A reconstruction of the events surrounding Damian Ahrendse’s, including the two versions of the police shooting which were contained in IPID’s case file. Animation: Viewfinder

The day after Damian died, IPID’s investigators went out to the scene in Wesbank and interviewed Andrew Konna. They did not retrieve the bullet that killed Damian, and IPID’s investigators appear not to have looked for blood splatters where witnesses believed he had been hit.

Then IPID’s investigation appears to have gone cold for several weeks over the festive season. IPID only formally registered the case a month after Damian’s killing. Most of the witnesses were only interviewed then, and photographs of the scene were taken 41 days after the shooting. It took IPID’s investigator eleven months to seize Thebus’s firearm for testing.

A photograph from IPID’s investigation of the scene where witnesses said police had fired at Damian. The photo was taken nearly six weeks after Damian’s death. Source: IPID case file

A previous Viewfinder exposé revealed poor investigative practices at IPID. When queried about these delays and observations in IPID’s investigation of Damian’s case, IPID’s head in the Western Cape Thabo Leholo maintained that “no IPID regulations were flouted” and that the crime scene had been properly “reconstructed”.

Though the investigation was imperfect and the evidence circumstantial, IPID’s investigator Happyboy Gigi still believed Thebus had a “prima facie case of murder” to answer for.

“The force he used was unnecessary and unjustifiable under the circumstances. There is no evidence that his life or that of his partner was in danger at the time,” he wrote.

In 2014, IPID referred the docket to a criminal prosecutor, who declined to prosecute Thebus and instead referred the case for an inquest the following year. Six years later, the inquest into Damian’s death has not been finalised. Leholo explained that IPID was “still attending outstanding magistrate’s instructions” before an inquest could go ahead.

In 2014, IPID also recommended that SAPS “initiate disciplinary proceedings” against Thebus on several charges of misconduct for the killing of Damian Ahrendse.

In South Africa, police discipline management depends on senior officers internally appointed by SAPS to investigate, lead evidence and preside over hearings in which their colleagues are accused of misconduct.

SAPS must initiate a disciplinary process when IPID completes an investigation and recommends an officer be charged with misconduct. This is so, even if its officials disagree with the watchdog’s findings against their colleagues. If a case progresses to a hearing, the SAPS officials appointed as “employer representatives” have wide powers over how the evidence from IPID case files is interpreted and presented, and thus over the outcomes of these hearings: “guilty” or “not guilty”. The police watchdog is excluded from this hearing.

This means that police accountability in the country pivots on the preparedness and impartiality of these officials. Yet, they are exempt from external checks and balances. If these officials are unprepared or choose to skew the available evidence in favour of an accused colleague, a “not guilty” finding is nearly inevitable.

Viewfinder has previously unpacked the consequences of this in an exposé on SAPS’s discipline management system. Our investigation showed that disciplinary proceedings were vulnerable to manipulation within SAPS, and that this needed to be taken into account in light of how often police officers emerged from these proceedings unpunished or with low sanctions upon conviction for serious offences.

Yet, the inner workings of these proceedings — and the conduct of SAPS’s evidence leaders — remain hidden from view. The tapes of Lieutenant Michael Thebus’s disciplinary hearing have provided rare insight into the proceedings from which even watchdog investigators are routinely excluded.

In the disciplinary case against Lieutenant Michael Thebus, SAPS appointed Captain Gerhard van den Bergh as the “employer representative”. He was tasked with calling witnesses and leading evidence.

Shannon Pearce, Donnecia Ahrendse and Andrew Konna were not called to testify, though Viewfinder has established that they were willing to do so. Konna has since passed away, though Viewfinder spoke to his stepfather, who said that Konna was willing to take the stand against Thebus.

Former SAPS Captain Gerhard van den Bergh. Source: Facebook

All three of these witnesses had implicated a police officer in shooting Damian. These witnesses also had information important to the case: what Damian was wearing on the day that he was shot.

There is little doubt that Damian was wearing a jacket. This jacket was, at least in part, black and red. Konna had said this in his statement. Thebus and Groenewald both described the clothing Damian had on after he was shot as “a brown T-shirt and a black jacket with a red stripe and white on the bottom”.

When interviewed recently, witnesses Pearce, Donnecia Ahrendse, Dominique van Wyk and Damian’s mother Klarina Reed all agreed that these descriptions were of the Manchester United jacket that Damian had on when he was shot. Reed has kept this jacket as a memento and can point out the holes that the bullet apparently made as it passed through Damian’s torso.

The jacket that Damian Ahrendse had on when he was shot, according to his family. Photo: Daneel Knoetze

When Van den Bergh questioned Thebus at his disciplinary hearing, the issue of Damian’s clothing came up. The exchange below has been translated from Afrikaans and edited for clarity.

“Both of them had red tops or t-shirts on,” Thebus had said, when asked what the suspect upon whom he had fired was wearing.

“Now are we talking about red or brown?” Van den Bergh asked.

“Red,” said Thebus.

“But, the deceased had a brown t-shirt on,” Van den Bergh said. Van den Bergh did not mention that Damian was also wearing a black and red jacket.

“According to me it was brown,” Thebus confirmed. At this moment during his testimony Thebus also did not mention that Damian was wearing a black and red jacket. This created the impression that there was a substantial difference between the clothing Damian was wearing (brown) and the clothing that the suspect upon whom Thebus had fired was wearing (red).

“And the difference between red and brown?” asked Van den Bergh.

“Yes, there was a difference,” Thebus said.

“So what you are actually telling us at the moment, is that there is a possibility that this chap that died was never even on the scene,” Van den Bergh said.

“When we saw the little guy lying there, I was absolutely convinced. I said to my colleague: ‘this is not the same guy,’” Thebus said.

This exchange between Lieutenant Michael Thebus and Captain Gerhard van den Bergh is contained in a segment produced by Viewfinder for Carte Blanche. The segment aired on 8 August 2020 and is accessible to DStv subscribers via Carte Blanche’s catch-up service here.

Viewfinder sent a query to Van den Bergh, who is no longer employed with SAPS, asking about the absence of certain witnesses from the hearing, his failure to mention Damian’s jacket during this exchange and questioning other instances where his leading of evidence appeared to support his colleagues’ claim to innocence. Viewfinder shared the case file and recordings with him, and asked for an interview or a response.

“I shall try to make time to study the material and listen to the records, but it will take some time,” he wrote via WhatsApp, while defending his track record as a discipline official who had apparently ensured the dismissal of over 200 corrupt cops over his career. He did not respond to a follow-up request a few days later.

In the absence of the other witnesses, Damian’s half-brother Dominique van Wyk was the only witness at the police hearing who testified that Thebus had shot at Damian. Van Wyk’s affiliation to the 26 Numbers gang meant that the credibility of his testimony was thrown into question.

During his closing statement in the hearing, Van den Bergh said that SAPS had accepted Thebus’s version and his claim to innocence in Damian Ahrendse’s killing. Even if Thebus had shot Damian, Van den Bergh said, he would have been justified in doing so. Van den Bergh did not fully explain why he believed such a shot would have been justified. The information available to him was that Damian had been shot in the back.

In his closing statement, Van den Bergh went on speculate about Damian Ahrendse’s character:

“When [Van Wyk] testifies that his 15-year-old brother used dagga, we have to ask the question: ‘Where to was he then on his way in life?’”

On 17 December 2013, Damian Ahrendse’s body was laid out on an autopsy table at Tygerberg Mortuary. On his wrist, the pathologist noted, were three rubber bracelets: one yellow, one green and one red. These are the colours of Rastafarianism. The yellow represents the mineral wealth of Africa. The green represents the beauty and vegetation of the promised land, Ethiopia. The red represents the blood of martyrs in the struggle for black liberation around the world.

Damian was born into a world, on the Cape Flats, in which bloodshed was a fact of life for coloured boys and young men. In the year that Damian was born, his half-brother Dominique Van Wyk dropped out of school at the age of twelve. Through Damian’s adolescence, Van Wyk rose steadily through the ranks of Wesbank’s street gangs and then, in prison, he was inducted into the 26 Numbers gang.

Reed did not want Damian to be caught up in Wesbank’s gang fighting because of Dominique, so she sent him away to live with her sister in Kraaifontein. It was from here that he returned to his mother’s house on the day that he died.

In the philosophy of Rastafarianism and in his love for soccer, Reed says, Damian found a way to escape the long shadow that his brother’s increasing prominence in the Numbers and Wesbank’s affiliated street gangs had cast over the family. At 15, he was coming into his own. He would come back to Wesbank on Friday after school full of new stories and experiences from the week. He would wait for his mother at the taxi rank and they would walk home together.

Damian Ahrendse’s mother said that he was forging his identity in Rastafarianism during his teenage years. Photo: Anton Scholtz

“He told me one day he wants to play for Liverpool, and I said to him, ‘Yes, my child, that is your dream, you can achieve it. I think you will end up there, don’t worry. It’s like the other stars in the Springboks that end up overseas. So you will also end up overseas, I think. You said Liverpool is your team,’” Reed recalls one such interaction with her son.

“Don’t worry mommy. I will work for you when I grow up,” Reed recalls him saying, when she despaired about Van Wyk’s gang activities and about the poverty that has remained a constant in her life.

When Damian was killed, she knew that the fight for justice would be a fight against the stigma of the connection with a top gangster. So she went door to door gathering signatures on a petition to confirm that Damian had “no involvement in gangsterism”.

Reed gathered 76 signatures. The petition became the basis for the file that she has carried with her ever since – on visits to IPID, to Kuilsriver Magistrate’s Court and uncounted trips into the Cape Town city centre in search of an organisation or government office where officials would listen to her. It was the file with which Reed first walked into Viewfinder and GroundUp’s offices in January 2020.

Damian Ahrendse was awarded this trophy as the top goal scorer in his age group at Wesbank Super Eagles Football Club in 2008. He had ambitions to become a professional soccer player, says his mother. Photo: Anton Scholtz

The file also contained a photo of the deceased Damian with a bullet wound to his chest, a birth certificate, a death certificate, a photo of Damian on a school trip and a diploma of merit that confirmed that he was a top goal scorer at Wesbank Super Eagles Football Club in 2008. This is all that remains of Damian’s short life. This and his mother’s memory of him.

“There are times that I’ll go to the grave site. Then I speak to him and say ‘Damian, you might just come tell mommy. What, what did go wrong that day?’” Reed said.

Viewfinder submitted a detailed query to SAPS Western Cape and SAPS head office, which included a request to interview Michael Thebus and Adriaan Groenewald. SAPS head office did not respond. SAPS Western Cape spokesperson Lieutenant Colonel André Traut said that the police could not make its employees available for an interview and declined to answer questions about the disciplinary hearing because it referred to an “internal” process.

Watch: The Death of Damian Ahrendse, a documentary short produced by Viewfinder which revisits the day that Damian died.