14 March 2024

South Africa’s commuter rail system declined because of corruption involving PRASA and a Spanish company. Archive photo: Ashraf Hendricks

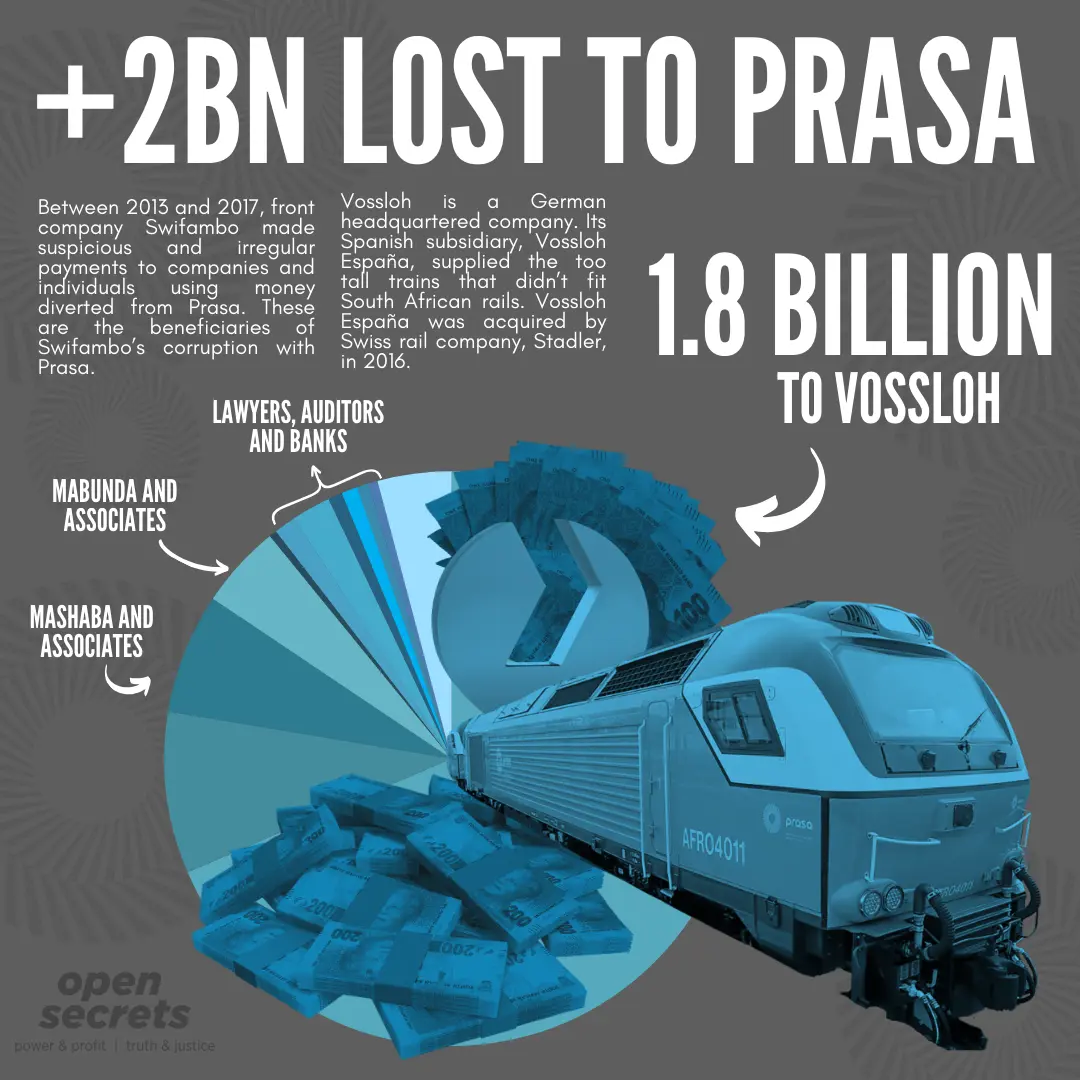

This article is the first in a series of articles on corruption in PRASA’s dealings with a front company called Swifambo Rail Leasing. It focuses on Vossloh, a European rail technology company, which made billions of rands through a dubious partnership with Swifambo.

In 2012, a deal was struck that contributed to the near collapse of the Passenger Rail Agency of South Africa (PRASA). The Swifambo deal for 70 locomotives led to billions of rands in losses for PRASA and accelerated the decline of passenger rail services in South Africa.

Swifambo, a front company set up shortly before the deal, partnered with Vossloh España — the Spanish subsidiary of Swiss railway stock manufacturing firm Stadler — to supply the locomotives. Stadler acquired Vossloh España in 2016 from German headquartered rail technology company, Vossloh AG. Vossloh España was owned by Vossloh AG at the time it partnered with Swifambo on the PRASA deal which was worth R3.5-billion.

In 2018, the Supreme Court of Appeal upheld a decision by the Johannesburg High Court declaring the contract corrupt. The court said that Swifambo had acted as nothing but a front for Vossloh in the deal.

The locomotives supplied by Vossloh, known as the Afro4000, were meant to improve long distance passenger services between South African cities, but were revealed to be too tall for South African railways. Yet PRASA ended up paying Swifambo R2.7-billion for the trains.

Swifambo went into voluntary liquidation in 2018. The trains are now being auctioned by Swifambo’s liquidators, Tshwane Trust, to recover amounts owed to PRASA.

Vossloh received R1.8-billion of the R2.7-billion Swifambo was paid by PRASA. According to the draft report of a 2017 investigation by forensic auditor Ryan Sacks, commissioned by the Hawks, and a separate investigative report by forensic auditor Jan Dekker, commissioned by the liquidators, Vossloh made the most money from the corrupt contract — even more than Swifambo’s director, Auswell Mashaba.

Yet Vossloh has not paid back a single cent.

Vossloh’s records show just how profitable the corruption at PRASA was for its European business. Before the locomotive contract, Vossloh had already scored a major cash injection from PRASA, when Its German subsidiary, Vossloh Kiepe, shipped 272 air conditioning units to PRASA in 2012 worth €80-million in a deal where there were “significant irregularities”, according to Sacks’s draft report.

That same year, Vossloh opened its South African headquarters, Vossloh Southern Africa Holding Company, in Midrand, Gauteng. A year later, in 2013, it landed the “megacontract” for the locomotives for PRASA through its front company, Swifambo. At the time Vossloh España agreed to partner with Swifambo to provide the trains, Vossloh AG’s profit was declining. The company’s annual report for the year ending 2011/2012 showed a 5.7% decline in sales. Then, in 2013, orders rose by more than 37% to €453-million. South Africa’s order of 70 locomotives made up more than half the value of orders Vossloh received in 2013.

The deal was set up to benefit a few at the expense of PRASA and South African commuters.

Between 2011 and 2015, Vossloh made ten payments totalling R88.9-million to companies owned by Makhensa Mabunda, a well-connected businessman who is believed to have set up the Swifambo/Vossloh deal with PRASA. Popo Molefe, then chairman of the PRASA board, has revealed in court papers that Swifambo director Mashaba identified Mabunda as the businessman who engineered the PRASA deal by inviting Mashaba’s company to submit a proposal for the tender.

The payments to Mabunda were flagged as suspicious in a report by the Reserve Bank in 2017, according to the Sacks report.

News24 first revealed the payments made by Vossloh to Mabunda in 2018, and Open Secrets referred to them in an article in its Unaccountable series on Vossloh in 2021. After the News24 story was published, Vossloh AG confirmed that it paid Mabunda and his company S-Investments about R90-million as an “independent sales representative” who simply acted as a middleman to bring “Vossloh España, the supplier, together with its customer Swifambo”. But there is more to it than that.

As Open Secrets reported in 2021, Sacks found that Vossloh had paid the startup costs of Swifambo in 2011 and 2012 — more than a year before Swifambo scored the PRASA contract and partnered with Vossloh España. And Mabunda’s companies continued to receive money from Vossloh three years after the startup costs were paid.

Vossloh had no legitimate reason to pay Mabunda, but so far nothing has come from the Reserve Bank’s report. There does not appear to have been any further investigation into whether these payments were potential kickbacks for Mabunda’s role in securing the billion rand contract.

And little action has seemingly been taken by PRASA to recover the funds that are so vital to improve services for commuters. Molefe, as PRASA chairman, filed papers in court in 2017 to compel the Hawks to investigate corruption at PRASA. But so far, the Hawks have made no progress in their investigation into the PRASA and Swifambo corruption case, and there has been no judgment in the court action to compel the Hawks to investigate these matters.

Swifambo’s liquidators have numerous ongoing civil claims to recover funds from Swifambo with regard to its contract with PRASA. So far the liquidators have auctioned 8 of the 13 locomotives Vossloh delivered for just under R100-million, but this is only a fraction of the R1.8-billion Vossloh made from the deal.

Nearly three years ago the Hawks told the Zondo Commission that the Swifambo investigation was “90% complete”. But responding to questions by Open Secrets in March, the National Prosecuting Authority said the case was “still under investigation” and no prosecutions can take place until the Hawks finalise the police work. Deputy Head of Public Prosecutions Rodney de Kock said other law enforcement agencies were collaborating on the case.

However, PRASA’s spokesperson Andiswa Makanda has told Open Secrets that the agency believes the Hawks are prioritising the case and the agency is “cooperating with law enforcement agencies involved in the investigations”. And the Special Investigating Unit (SIU), which investigates matters referred to it by the Presidency, announced in February 2024 that its eye was now on the Swifambo contract, and investigations into Mashaba and PRASA are underway.

Spanish authorities in 2022 submitted a Mutual Legal Assistance (MLA) request to South Africa in relation to an investigation into Vossloh España and others involved in the deal. Makhensa Mabunda is one of the individuals named in the Spanish MLA request. The NPA declined to comment to Open Secrets on the status of the MLA request.

Vossloh España’s parent company, Stadler, also declined to comment on the allegations of its involvement in corruption with Swifambo, saying the matter is before the courts in South Africa.

The Reserve Bank told Open Secrets that it “does not comment on ongoing investigations” and did not “have further details that can be provided at this time”.

Mabunda was the inside man behind the Swifambo deal, and bank records show just how much he gained from being well-connected. Our next article in this series focuses on the man who made the Swifambo deal possible, and who is complicit in creating the access to transport struggles faced by South African commuters today.