22 June 2015

The Californian-born transport company, known as Uber, first came to Cape Town in August 2013. Two and a half years later, it has approximately 2,000 drivers in South Africa’s three main cities, many more thousands of users, and ambitious plans for expansion. The company is rapidly reconfiguring the metred taxi industry in the country.

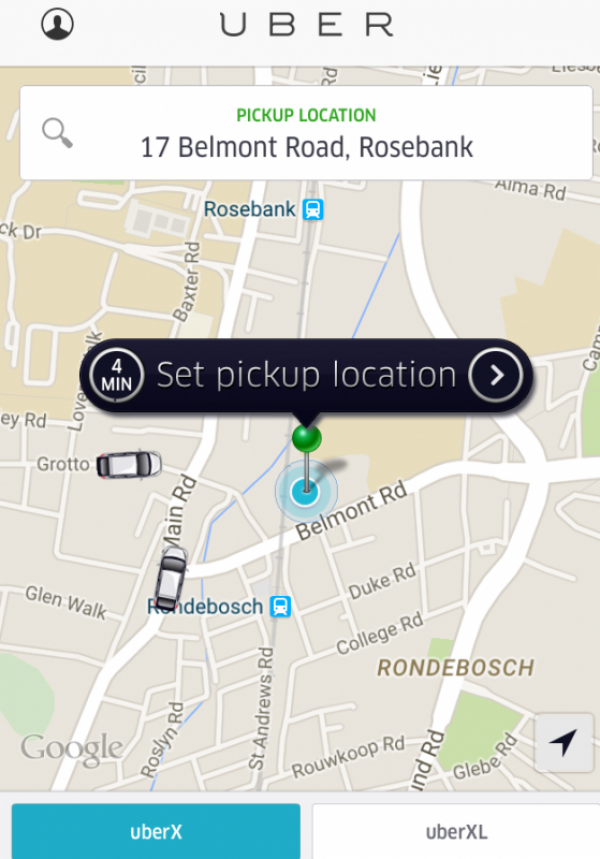

Uber is a taxi service that allows users to order a cab quickly and easily from a cellphone by downloading the Uber app. Based on your location, the app connects you to the closest driver and users can track the progress of their taxi in real time on a map. The software also links directly to the user’s bank account so no money changes hands. Uber markets itself as “the safest, simplest, most affordable and reliable ride”.

Marcus Low lives in the Cape Town CBD and is fully reliant on public transport because he only has partial sight and cannot drive. He now uses Uber for 90% of his transport and much prefers it to the metered taxis he used to take, which he often found to be unreliable.

“Uber has made my life dramatically easier,” said Low. The fact that you can see exactly when the car will arrive and call the driver directly makes a big difference. In his experience, Uber in Cape Town responds quickly to customer concerns. The service is also slightly cheaper than other taxis and he finds not having to use cash an additional benefit.

Uber makes its money by taking 20% from the cost of every trip, but is careful to describe its core business as “connecting riders to drivers through smartphone technology”. It owns no cars, has no employment contracts with drivers – who it refers to as “driver partners”, and there are very few obligations between drivers and the company.

Uber has also been the object of protests from competitor taxi drivers in Cape Town.

Owen Chibanda from Ilitha Park in Khayelitsha has been driving a metered taxi for five years. He is clear about the fact that Uber drivers have taken away some of his customers. “We know them (our old customers) and now we see them holding their phones waiting for an Uber”.

Chibanda earns between R2,000 and R2,500 a week, but he has to pay R1,500 to his employer for renting the taxi. His take-home pay is low. He has friends who drive for Uber and plans to join them once he gets a South African driver’s license. He hopes that once he switches over to Uber he’ll earn more.

Samantha Allenberg, Communications Associate at Uber Africa, sees the new competition as a good thing and points out that some taxi operators have already partnered with Uber in order to expand their businesses. According to Allenberg, one of the main advantages for Uber drivers is that they are self-employed and therefore “able to work the hours and days they choose, and fit their work into their obligations and family life”.

Stephen Peterson has been an Uber driver in Cape Town for six months since leaving a job in construction. He owns the car that he drives and usually works a 12-hour shift, six days a week. He estimates his weekly earnings to be about R7,000, which means that after covering fuel, insurance, and car repayments he is left with at least R2,500. When asked how he likes working as an Uber driver he says, “so far so good”.

But many Uber drivers don’t own the cars they drive. Another driver, who asked not to be named, told GroundUp that his weekly pay is less than R1,000. After Uber takes 20%, he splits the earnings equally with his employer, although he is required to pay for the fuel. Because the driver is employed by the owner of the car, he does have an employment contract, pays Unemployment Insurance, and is protected by the Basic Conditions of Employment Act. Despite his small wage, he said working with Uber is “100% better than driving a normal taxi”.

The fact that Uber doesn’t employ any of its drivers has become a major point of contention elsewhere in the world. Most recently, the California Labor Commission ruled last week that an Uber driver is an employee, is not an independent contractor, and should be entitled to various benefits.

Allenberg stresses that “this ruling is non-binding and applies to a single driver”, noting that Uber has appealed the ruling in the US and that in all countries “drivers are our partners and not employees”.

In South Africa, no such challenges have yet been made. Nicola Arendse, an Attorney at the Cape Town labour law firm Bagraims, says that there are many situations in which companies use independent contractor relationships because “they consider the [employment] regulations too onerous”. In Uber’s case, the substance of the arrangements between the company and the driver would need to be examined against the country’s legislation.

“Companies may be contracting out of basic rights,” says Arendse, and this is problematic.

Unlike other employees, as independent contractors Uber drivers have no recourse at the Commission for Conciliation Mediation and Arbitration (CCMA) to deal with labour disputes. If they are removed from the Uber system there is very little they can do. At present, users must ‘rate’ their driver on a scale of 1-5 stars after every trip. Uber monitors these ratings and if a driver’s rating falls below the national average (around 4.5), the driver is suspended and needs to attend a re-training session.

Peterson told GroundUp that while he was satisfied with his job overall, there was a feeling that Uber “treats riders as better than drivers”, and that “if things are going well for the company you are nothing to them”.

He said most drivers were too scared to say anything and there was no form of collective organisation among the drivers. Allenberg responded to these concerns saying that “Uber partner drivers have a direct line into the Uber team and we will continue to work with them to ensure their small businesses thrive”.

This ‘direct line’ is an email address specifically for drivers to contact the company, and there is also a daily one hour time slot during which drivers can go to the Uber offices in Greenpoint to discuss any concerns.

The price of an Uber trip is another area of concern for some drivers as they have no influence in determining this. Uber has decreased the cost of a trip to R6 per kilometre for the month of June, which is rands lower than any other metered taxi company in the city. This price drop came just after a rise in the cost of fuel. In an email to users, Uber claims that the lower price will create “more trips for every hour, and more earnings for every hour on the road”.

According to Allenberg, the incentive is worked out such that if the driver earns less than they would have, Uber will compensate. It seems there are drivers that don’t understand the scheme. Although they might not gross less, drivers do have to do more trips to make the same amount.