Workers drill for water from the Cape Flats aquifer in Mitchells Plain, Cape Town. Archive photo: Ashraf Hendricks

27 February 2018

Water will probably continue to flow through Cape Town’s taps throughout 2018. That’s because of the huge effort by most residents of the city and surrounding municipalities, as well as many farms, to save water.

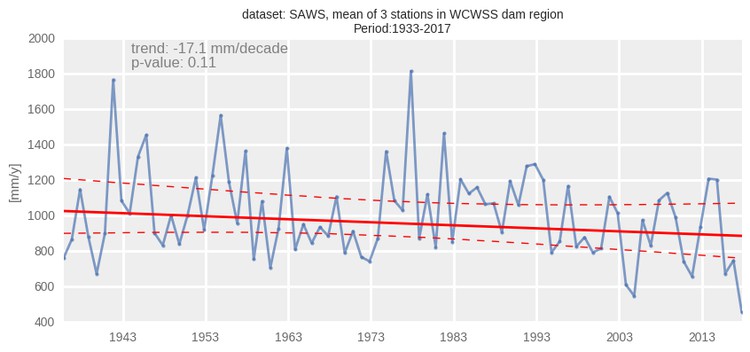

But the drought is not yet over, and the Western Cape’s long-term rainfall average appears to be declining, probably due to climate change. This is why government, national and local, is planning to supply the city with new sources of water.

Here we explain what Cape Town’s water supply will probably look like in future. Even more important than supply, and much more affordable, is reducing the amount of water we use for the long run (which is called demand management). That we’ll discuss in an upcoming article.

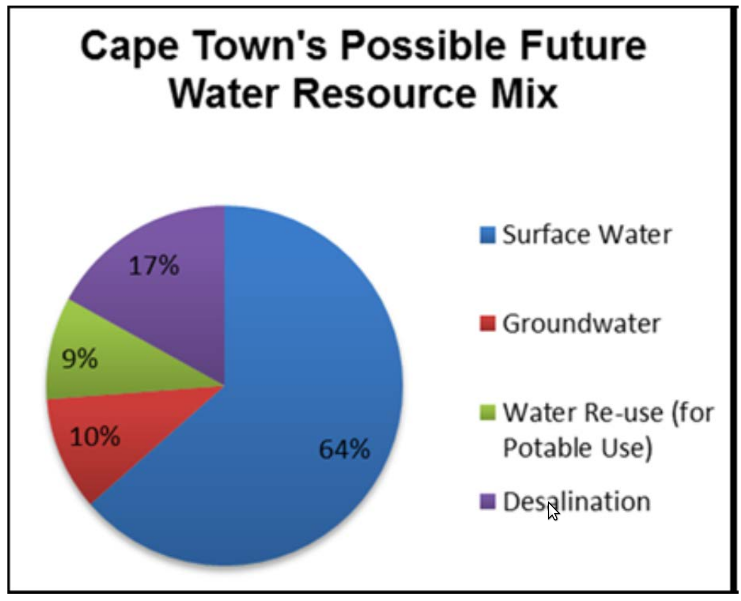

More water can get to the city by increasing the supply of water to the dams, desalinating sea water, using groundwater (water buried underground) and spring water (which is also groundwater), and recycling water in the city’s sewage system.

These are important numbers to keep in mind for the rest of the article. Also, please note that most of the numbers used are estimates. As new information comes in, government departments update their figures to be more accurate.

For the past few weeks Cape Town has been using about 500 million litres of water daily. There are about 4 million of us, so that works out to about 125 litres per person daily (including business use and leaks). A short while back the city was averaging 600 million litres per day. In times of plenty it has been about 900 million litres daily on average, and even higher in summer..

Also, surrounding municipalities use about 60 million litres daily (100 million litres in times of plenty), and farms also use another 650 million litres of water daily on average, although this varies dramatically from year to year, and depending on the time of year.

About 140 million litres evaporates daily from the dams but that also varies greatly between summer and winter, and depends on the weather and how full the dams are.

Nearly all Cape Town’s municipal water comes from six big dams (in order of size): Theewaterskloof, Voëlvlei, Berg River, Wemmershoek, and Steenbras Lower and Upper. A miniscule amount of water is supplied by dams on Table Mountain.

Professor Neil Armitage, an engineer at UCT, explained to GroundUp that making dams bigger does not necessarily increase the amount of water they hold. The main way the dams get water is from rivers flowing into them. A small amount of their water comes from rain falling directly on them.

Also, although Theewaterskloof holds more water than all the other dams put together, it’s got an unfortunate problem: it’s wide and shallow and therefore more water evaporates from it. By contrast, Wemmershoek is narrow and deep; it loses much less water through evaporation, but it also only has one seventh the capacity of Theewaterskloof. The point is that simply increasing dam sizes may be pointless or even counter-productive because of the increased evaporation.

There is one very important project to increase the amount of water getting into one of the dams. The national government is implementing a project to pump more water from the Berg River to Voëlvlei; it’s called the Voëlvlei Augmentation Scheme. It will add about 60 million litres daily. This was originally scheduled to come online in 2024 but a Department of Water Affairs spokesperson told GroundUp it had been fast-tracked to 2019.

The City also negotiates with private dam owners to augment our water supply. For example, quite a bit of water was supplied this summer from a private dam on the Palmiet River.

Water collects under us in sand and gravel in what are called aquifers (read more here). Cape Town has three main aquifers: The Table Mountain Group aquifer (TMG) is the largest and runs through the Western Cape up to Kwazulu-Natal. The Atlantis aquifer is north of the city, and the Cape Flats aquifer is on, well, the Cape Flats. The latter is also the source of much of the Philippi Horticultural Area’s water.

The City has started drilling for water from the aquifers. It’s a relatively affordable way of getting good quality water. But it is not without risks, and the City has to be careful. We don’t understand enough about how the aquifers work. This is especially so for the TMG, and drilling in one part may have dire consequences for people dependent on another part of it. GroundUp will soon publish an opinion piece by a scientist concerned about how municipalities are using the TMG.

Another concern is that if too much water is extracted from the Cape Flats aquifer, it could dry out, and even worse, sea water may fill the aquifer, creating a long-term ecological crisis.

Nevertheless, carefully planned aquifer extraction likely has an important role in Cape Town’s future water supply. The City is already getting 5 million litres daily from Atlantis, and is implementing a project to get a further 20 million litres daily by later this year. The City expects eventually to get 80 million litres daily from the TMG (one City document estimates 40 million litres daily by June 2019). It also expects to get 80 million litres daily from the Cape Flats aquifer. Note though, that these are maximum estimates.

The City is building three short-term temporary desalination plants. It expects to be getting 7 million litres daily each from plants at Strandfontein and Monwabisi by May. It also expects 2 million litres daily from a plant at the Waterfront in March.

A pilot permanent desalination project is being built at Koeberg. The City is considering other sites along the coastline. These large permanent desalination plants could be operating in two to three years if the state moves quickly.

But desalination also has its problems. First, it’s extremely expensive, especially temporary desalination (more on this below). Second, it uses huge amounts of power, and third, it pumps brine back into the sea which may cause ecological problems.

Perhaps a hundred years from now, history books about Cape Town’s 2018 water crisis will include photos of people queuing for water at the Newlands spring. The reality though is that spring water, at least in the near-term, can only provide a small amount of water to the city.

The City is extracting about 3 million litres of water daily from the Albion Spring in Newlands. It is extracting a further 1 million litres daily from a spring in Oranjezicht. This is less than 1% of daily municipal water usage.

Our faeces, urine, dishwater, washing machine water, and shower water, goes into the sewage system and eventually lands up at one of the city’s waste treatment facilities. It’s possible to turn this back into good quality drinking water. Windhoek already does. Cape Town can eventually get nearly a third of its daily water supply through recycling.

The City intends to recycle 10 million litres daily from its Zandvliet facility by June this year, increasing this to 50 million litres daily by December 2021. It hopes to get 10 million litres daily from its Cape Flats facility by June, increasing it to 75 million litres daily by December 2021. It intends to get 20 million litres daily from its Macassar facility by June 2019, 10 million litres from Potsdam by June 2019 and 75 million litres daily from Athlone by December 2021. (About 10% of Cape Town’s water supply has already been recycled for a number of years and is sold to selected users.)

Some of this water will be put back into the aquifers. And depending on need, some of it will be made potable for use by Cape Town’s residents.

This is definitely one of the most sustainable ways to augment our water supply, but it isn’t cheap (see below).

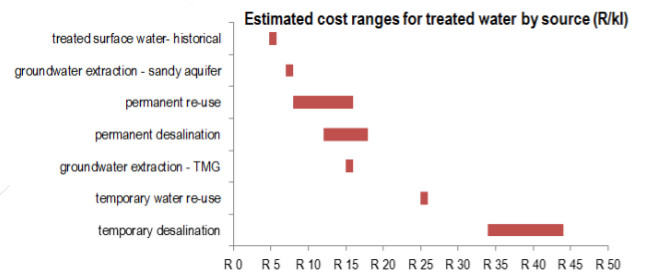

Getting water from our dams is by far the cheapest option, at about R5 per 1,000 litres. The table below shows the cost of the new ways of providing water to the city. By far the most expensive are the temporary desalination projects currently on the go. At a minimum of R34 per thousand litres this clearly is not a financially sustainable way of quenching our thirst. Extraction from the Cape Flats and Atlantis aquifers is the cheapest option after dam water, followed by permanent re-use. Desalination at a permanent plant is also not cheap, but it is definitely an option.

Whether we have a Day Zero in 2019 depends on the upcoming winter rainfall and our ability to continue to use water sparingly. If we have another drought-stricken year, the taps will likely run dry for at least some part of next year. But droughts do break, and the long-term future for the city’s water supply looks promising.

Thanks to Professor Neil Armitage and technical staff at the City of Cape Town for assisting us with this article. GroundUp takes sole responsibility for any errors.