Theewaterskloof Dam in May 2017. Photo: Ashraf Hendricks

18 July 2017

Cape Town’s dam levels were at just over 26% on 17 July, almost 17% down on the same week last year. The City says it is hard to use the last 10% of water in dams, meaning the dam levels are essentially about 16%.

For a city that relies on historically wet winters, these figures are daunting. What is more, the future looks drier. The Western Cape government’s Disaster Management Directorate estimates rainfall will decrease by 30% by the year 2050. We asked various government officials what the plan is to prevent the city’s taps running dry.

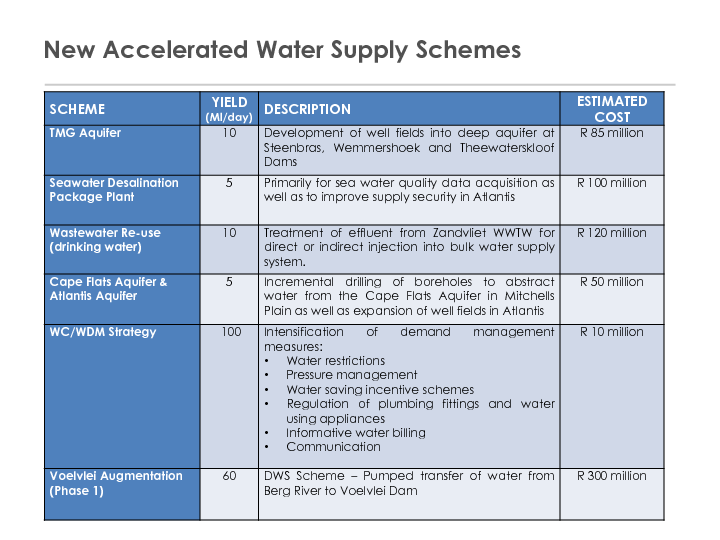

Government has several projects on the go to increase the water supply to Cape Town. We explain these in this article. But all of them added together come to fewer than 100 million litres per day in the short to medium term, about 15% of our daily water consumption. It’s not enough. We have to use less water.

Organisations and people who claim there is some panacea other than reduction of consumption (which also might not be enough if we don’t get more rain) are simply wrong. This is not to say that ways of providing more water to the city should not be explored, but neither should their effect be exaggerated.

Xanthea Limberg, the mayoral committee member responsible for water, says that stricter restrictions will be implemented to reduce consumption. Currently, the City is under level 4B restrictions which limits water usage to 87 litres per person per day.

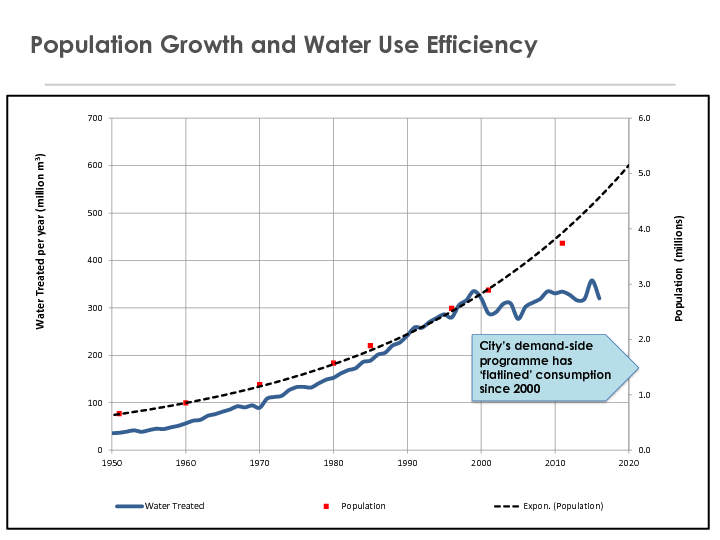

The City wants daily water consumption to drop to 500 million litres. Average daily consumption for the week ending 16 July was 613 million litres, an improvement over the past few years, but still too high.

City-supplied figures report that 65% of its water goes to formal residential customers. Half of that is used for non-essential purposes – filling pools, watering gardens, washing cars and so forth.

Fixing leaks and targeting industrial customers (who use 4% of municipal water) “will not make the required difference”, says Limberg.

Limberg said about 75 people have been employed in the past month to handle water complaints. They have to identify problems, find leaks and make sure leaks are repaired.

A Water Advisory Committee made up of experts from various fields – academia, business, and civil society – will provide advice and oversight to the City.

A Water Resilience Task Team has also been established, led by Craig Kesson, to co-ordinate the City’s response to the crisis. Limberg said the team “is working on a number of sub-projects across the short term.”

On 19 June, the City posted a Request for Information (RFI) to find possible not-for-profit and for-profit businesses willing to enter into a partnership with the City to establish water reclamation and desalination plants.

Desalination means purifying seawater into fresh water. The partners would “supply, install, and operate temporary plants at various locations along the sea shore and at certain inland locations,” said Limberg.

The goal is to have the first plant in operation by the end of August for a minimum of six months. The RFI closed on 10 July. Further plans for medium-term desalination and water reclamation will be guided by the results of the RFI. It’s not yet known how much water this will yield.

Limberg said the City was looking into renting off-shore desalination units. These units could “yield up to 500 million liters per day” said Limberg. As for details on the timeframe, provider, and number of units being considered, Limberg said, “It is too soon to say at this stage.”

Aquifer extraction is when natural underground rock layers, saturated with water, are drilled into and the water pumped to the surface. According to a 2012 map of Cape Town’s aquifers, the City has significant underground water.

The City has been studying extraction from the Cape Folded Mountain Belt, or Table Mountain Group (TMG) aquifer, which runs from Vanrhynsdorp to Mossel Bay. The project is scheduled for 2022 to 2026.

Limberg said the reason for the delay is due to a national project that takes priority: the Berg River to Voëlvlei Augmentation Scheme. The TMG project will only begin after phase one of the national project is completed.

However, the City is accelerating pilot drilling into the TMG Aquifer for a yield of two million litres per day. The plan is to incrementally add boreholes and reach the goal of ten million litres per day. The estimated cost of building this is R85 million.

The Camissa spring water flows through a series of underground tunnels from Table Mountain into the sea. An advocacy group called Reclaim Camissa is urging the City to use this water.

The potential of harvesting this water has been explored by the City for its ability to contribute to potable water supplies. However, Limberg said the City has found that it is not worth the expense: “Filtration and disinfection barriers would be required to protect community health, as would a pressure feed into the adjacent network and additional staff to control the treatment process,” Limberg said. However, she said it would be most cost-effective and simple to use the water for alternative purposes, like irrigation and industry. The City is currently preparing a licence application for further use of the springs.

More research is needed to estimate the yield of the Camissa spring water, and no doubt many supporters of Reclaim Camissa disagree with the City’s assessment.

Water reclamation is a polite way of saying “extracting water from shit”. Limberg said the City “has set the wheels in motion” for a wastewater reuse plant at the Zandvliet Waste Water Treatment Works. She said the plant would be capable of producing ten million litres of “high quality drinking water per day” for the central and southern suburbs. Estimated cost is R120 million to build the plant.

The provincial government did not address any of GroundUp’s questions but referred us to Limberg and the City.

The National Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS) has plans to divert water from the Berg River to the Voëlvlei Dam under the Voëlvlei Augmentation Scheme. The project has been approved for acceleration by the Minister of Water and Sanitation for final delivery in 2020, though this date is dependant on “securing the funding off-budget and finalising the designs of the civil engineering works,” said Ratau Sputnik, spokesman for the DWS.

Construction is supposed to commence in 2019 and the projected cost is R550-million. Currently, the project is undergoing an environmental impact assessment.

Sputnik said that “at this stage no dredging of dams are planned.” He said that most of the dams that supply water to the City are constructed in regions with little silt deposit accumulation. When asked if there were plans to build additional dams, Sputnik said “not at present,” citing lack of available water and suitable, undeveloped sites.

However, Sputnik said “options to raise one or two smaller dams in the system exist and are under consideration.” For example, the tender for the raising of the Clanwilliam dam (located on the Olifants River) is in its “final stages of consideration.” As soon as the project is awarded to a construction company, it will begin.