Temporary housing for Imizamo Yethu residents on a sports field in Hout Bay. Photo: Ashraf Hendricks

11 July 2017

In the first days of July, Hout Bay was at times cut off from Cape Town when hundreds of residents of the Imizamo Yethu informal settlement cut down trees and barricaded roads leading into the suburb. Police and residents fought with each other. One man, Songezo Ndude, was shot dead. The protesters had been living in temporary accommodation on a sports field. We look at what caused this.

On 11 March a devastating fire in Imizamo Yethu left several thousand people homeless. It was one of the worst shack fires in recent history in the Western Cape, but it was neither the first nor the last in Hout Bay.

Fire is a constant risk in Imizamo Yethu. It spreads rapidly because homes are built close together, often less than one metre apart. Fires are common where residents do not have electricity and therefore use paraffin, candles and open flames, or where electrical connections are illegal and unsafe. It is often impossible for emergency vehicles to get to positions where they can douse fires.

Other than providing formal brick housing, another solution the City proposes is “reblocking” (explained here) – creating a formal layout on an informal settlement with spaced plots, services, access roads and pathways. The City has done this successfully before but it isn’t easy, and each informal settlement presents unique challenges.

After the fire, the City announced plans to “superblock” Imizamo Yethu. It committed over R90 million to the project and an additional R44 million for electrification. The problem was that for reblocking to take place, people who had lost their homes would have to wait longer before they could rebuild their shacks.

In April, Mayor Patricia de Lille announced that the community had agreed to the plans. She said at a press conference held with community leaders that reblocking would be done in three months. But even as she said it, some residents had already begun rebuilding their shacks, making it impossible to proceed with reblocking.

From the outset there were mixed reactions to the City’s plans. Many residents supported reblocking, but others faced difficulties while reblocking took place. Victims of the fire were moved to temporary relocation areas – accommodated in tents, two marquees, community halls and other temporary structures.

Some people refused to be moved to these places, which they found crowded and uncomfortable. They chose instead to find shelter on the mountain or rebuild their shacks.

After the April press conference, people were moved out of the marquees and into temporary one-room, three-by-three-metre shacks on a sports field. Many of them were renting shacks, and they were now registered with the City to get shacks of their own.

On top of this, many residents do not trust the City to reblock in an acceptable timeframe. Community leaders say people who were moved to community halls after a fire in 2004 spent a year there before they gave up on being resettled, and rebuilt their shacks. GroundUp spoke to a resident who was moved to make way for roads in 2007. He says he and his family were moved to a temporary home and told it would be for only three months, then later told six months. They have never been relocated.

In the first days after the fire on 11 March, some shack owners started to rebuild. The City immediately responded with demolitions. On 19 March the City obtained a court interdict against people rebuilding their shacks. Residents continued rebuilding nonetheless. Members of the community did not in the end oppose the interdict, and it became a final order of the High Court on 1 June.

The City did not enforce the interdict while it was engaging with the community.

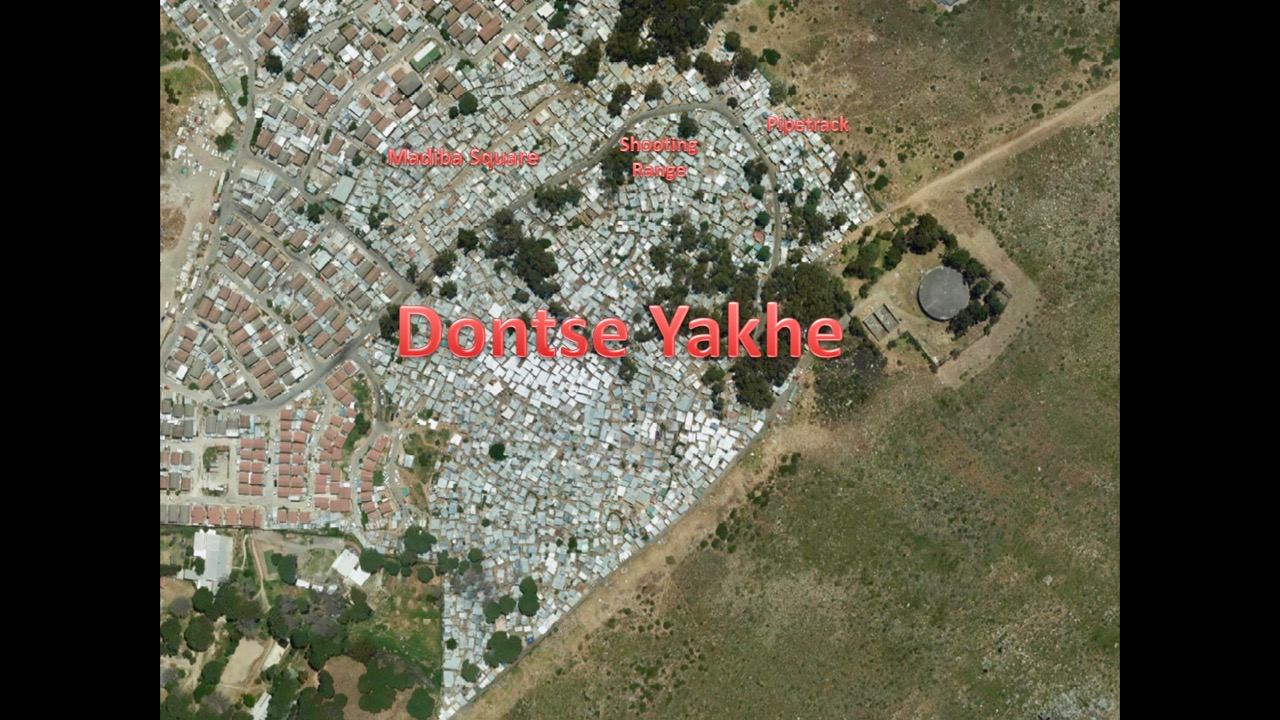

Some residents did agree to stop rebuilding and kept to this. However, in Madiba Square area of Imizamo Yethu, there were some demolitions with voluntary dismantling in late March. Part of this area was then reblocked.

Others however wanted the City to present clear plans on paper with timeframes and a memorandum of agreement. These were not forthcoming and so they rebuilt. By the end of May, the area for reblocking was almost completely filled with shacks.

Divisions in the community for and against the reblocking, but more specifically on how it is to be implemented continue.

Immigrants who live in the settlement were also wary of how they might be treated in the City’s formal process.

Many of the people displaced by the fire are already listed as beneficiaries for the Imizamo Yethu housing development project. Some of them have large shacks and rent out space or rooms in their shacks. Beneficiaries of the housing project want it completed before reblocking takes place. Then, when they are moved to their RDP houses, they will give up their shacks.

The people who have been renting from them will then be resettled in the informal settlement, but this time with it having been reblocked. This latter group (who rent shacks) appears to make up most of the people who have remained in temporary houses provided by the City, and not rebuilt.

Since the City obtained its interdict on 19 March and the mayor announced reblocking on 13 April, only a small section of Madiba Square has been reblocked.

Many people expected the City to act on the interdict and commence demolitions after 1 June, but the City did not act.

Frustration over delays in reblocking and anger about the absence of a memorandum of agreement with the City bubbled over in July. Protesters said they were tired of having to live in temporary shelters with seemingly no end in sight. They had also had to endure an awful Cape Town storm while in the temporary shacks. They took to the streets in violent protests.

The Mayor then recommitted the City to accelerating reblocking.

But to do this, the City will have to relocate or persuade over a thousand people who have signed a petition against being moved, and remove or demolish the hundreds of homes that have already been rebuilt.

A showdown is looming. Zara Nicholson, spokesperson for the mayor, says: “It has become necessary to enforce the … interdict due to the intimidation, threatening, harassing and assaulting of persons on site working on the super-blocking … There has been and will be further engagement with affected persons. If engagement fails, we will proceed with an eviction application.”

The City has made mistakes in the reblocking process. Residents remember unfulfilled promises. But the multitude of un-nuanced tweets and Facebook comments condemning either the City or the protesters show a lack of understanding of how complex and frustrating the situation is for all involved.