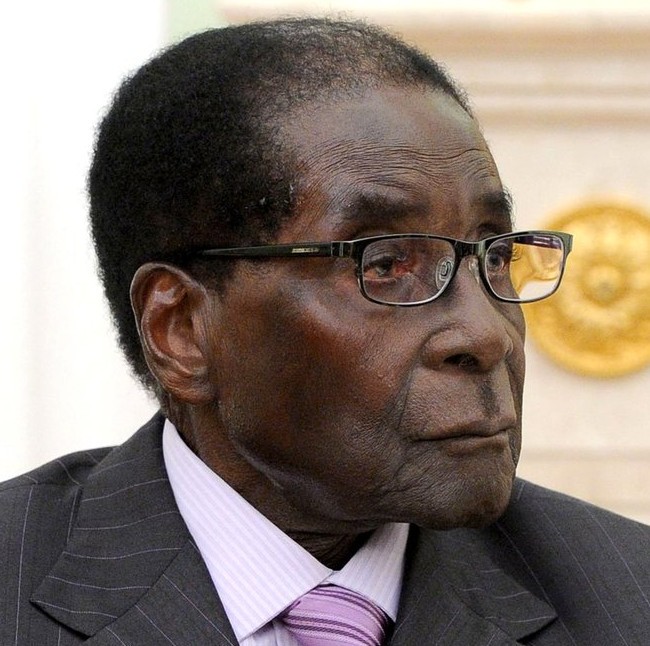

The author writes that Mugabe has failed Zimbabwe. Photo by www.kremlin.ru via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 4.0)

19 August 2016

I am a Zimbabwean who has been living in South Africa for about a decade. I recently visited for a family event. What I saw saddens me: people are struggling to survive.

While in Masvingo Town I found out why people wake up so early. At about 7am one morning I got to the only Post Office where I encountered a long winding queue.

People queue to withdraw money from as early as 5:30am. Some wanted to withdraw from the ATM while others waited for opening time. The reason for this is you are only allowed to withdraw a certain amount per day depending on the availability of cash the bank has that day. People queue early in case the bank runs out of money.

Once you manage to get a few US dollars for the day, the currency now used in Zimbabwe, you have to go about buying daily necessities. But you have to follow a strict budget lest you use the whole amount and fail to withdraw money for transport back home.

I tried to open an account first with Central African Building Society (CABS) in Masvingo. A security guard for the bank said I needed a payslip to do this. I insisted that I sell tomatoes so I would like to bank with them, but don’t get a payslip. But he showed me the requirements on a form, and indeed, I had to have a payslip.

I then tried at Standard Bank. “We no longer accept new accounts,” a bank official assisting clients in the queue told me.

It’s not clear to me how most people open bank accounts.

In both Masvingo and Harare I could see informal traders, mostly young people between the ages of 20 and 30, selling goods such as second-hand clothing, electrical gadgets and vegetables.

In Harare I spoke to a vendor who told me that since he completed school years ago he has never been employed. He decided to make a living out of vending. He was selling electrical gadgets near Eastgate Mall in the capital.

I visited several high density suburbs in Harare. Unemployment is massive. Youth, mostly men, can be seen milling around bottle stores, four to five people sharing a popular beer called “Scud” that costs about one dollar. They would each have contributed a portion to the cost of the drink.

I met a woman who lives in Mpumalanga, South Africa. She was visiting her parents in Masvingo. She had brought them blankets, clothes and a wardrobe for them, but they were all confiscated at the Beitbridge border post on the Zimbabwean side, because of new regulations on the importing of goods. “I am now stranded. The few rands I am left with are not enough for me to buy this stuff,” she said. On that day R100 could be exchanged for $6.80.

A young man I met told me, “I have to hunt for broken up cars and fix them at a negotiable price starting from US$5. I cannot come up with a standard price because motorists will not be able to afford the prices. At times I have to do it almost for free for goodwill,” he said. He completed a four-year electrical engineering course with Harare Polytechnic three years ago and has never secured employment.

One night during my stay he left for Johannesburg to sell goods. “I have to live with the reality that if I don’t do this who else will feed me? My mother used to sell dolls in South Africa some time back, but she is now grown up. It’s my time to support her,” he said. At times, like other friends of mine, he goes hungry.

Robert Mugabe has failed the people of Zimbabwe. At the same time the #ThisFlag movement, which is challenging his rule, was only present in some of the places I visited, mostly Harare.

The situation is desperate. I remember a time, in the early 90s, when there weren’t queues, when youth who had graduated from universities would be employed; they wouldn’t have to sell tomatoes in the street. And poor people got enough to eat.