Report shows dangerous levels of pollution in Cape Town’s rivers, vleis and estuaries

Quality of water bodies has declined over 40 years

Sailing on Zandvlei despite high pollution levels. Photo: Steve Kretzmann

- A new report shows that Cape Town’s rivers, vleis and estuaries have been getting worse for 40 years, with the exception of a few years.

- In the rivers the problem is mostly E.coli which is a bacteria found in faeces.

- In the vleis and estuaries the problem is mostly phosphate.

- The report says the pollution also threatens the city’s ecosystems which support plants and animals some of which are only found here.

- The City of Cape Town plans to rehabilitate and restore these bodies of water “in line with the City’s commitment to be a water-sensitive city by 2040”.

A new report reveals that water pollution across Cape Town’s rivers, vleis and estuaries has been getting steadily worse for 40 years, except for a few years.

The 88-page Inland Water Quality Report summary, released on 9 February, shows worsening pollution except for a slight improvement between 2010 and 2015. In a footnote on page 22, the City warns that the rivers, vleis, and estuaries are so polluted that swimming is not recommended.

The coastal water quality report was released a year ago, and revealed widespread pollution of the marine environment. But this is the first inland water quality data made publicly available since the 2016 results contained in the 2018 State of the Environment Report. The latest data from 242 testing sites shows that many of our rivers, vleis, and estuaries have over time become so polluted that swimming or wading is not advised.

The environment – a major attraction for residents and tourists – is also affected. The report notes that “some aquatic ecosystems support plant and/or animal species that occur only in a restricted area in certain watercourse types in parts of town, and nowhere else in the world”. “Sadly, however, many of these ecosystems are highly threatened.”

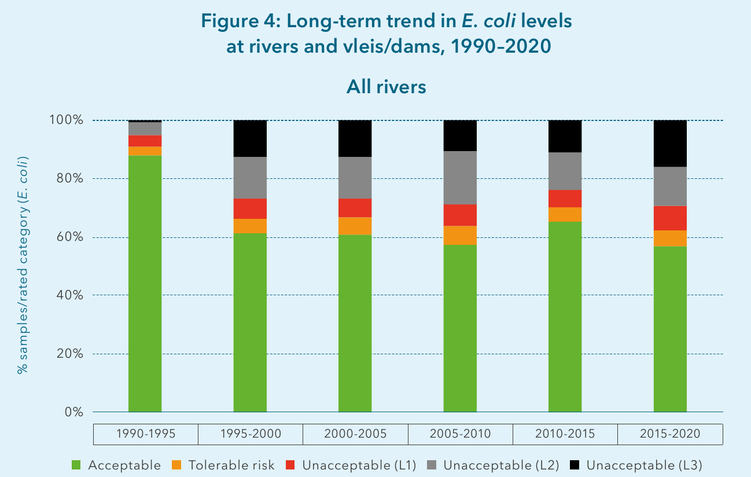

A graph from the report shows worsening E.coli levels over a 30 year period in Cape Town’s rivers.

What is being measured

The report focuses on two indicators of pollution: E.coli levels and phosphate levels.

E.coli is a bacteria found in human faeces (and that of other mammals) and is an indicator of other disease-causing microorganisms, or pathogens. E.coli is measured as colony forming units (cfu) per 100ml. The City considers 2,500cfu per 100ml or less to be acceptable for recreation such as canoeing, fishing, or sailing. The amount of E.coli allowed to be released into the environment by sewage treatment works is 1,000cfu per 100ml.

The phosphate levels indicate nutrient levels in the water. While aquatic plants require some nutrients, an oversupply of nutrients such as phosphorus and nitrogen leads to blooms of blue-green algae which release microcystin toxins, which can make people sick.

“Depending on the level of exposure, cyanobacterial blooms and their cyanotoxins can cause a wide range of symptoms in humans,” states the report. These range from headaches to stomach cramps and vomiting.

The rapid algal growth from high nutrient levels also leads to plant matter dying and decomposing, which removes oxygen from the water and can cause fish die-offs. Fish die-offs occasionally occur in water bodies such as Zandvlei.

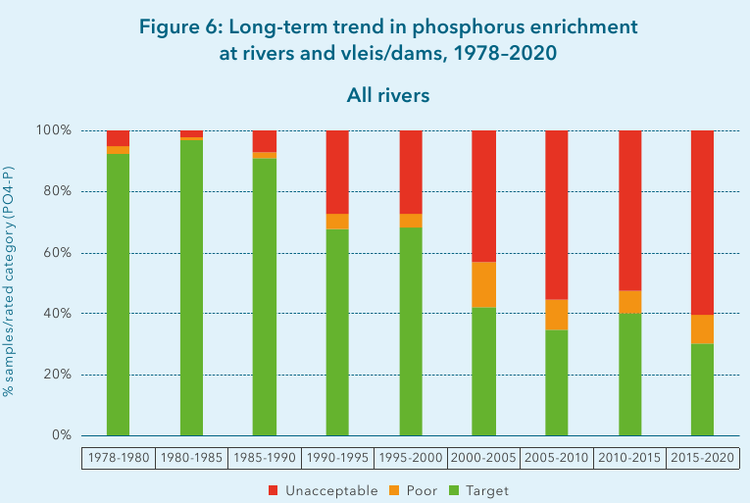

This graph from the report shows worsening phosphate levels at rivers and vleis over the past 40 years.

The state of the rivers

The report reveals that many of Cape Town’s rivers are highly polluted with E.coli, while most of our vleis and estuaries contain unacceptably high levels of phosphates.

Just over half of samples over the latest five-year period (2015 – 2020) show levels of E.coli which the City deems to be acceptable levels of E.coli, but the report does not say where these samples are taken, so there is no way of determining from the report whether there are stretches of river within the city boundaries that are likely to be acceptable for recreational activities.

Focusing on specific river catchments, the report shows that tests within the Salt River catchment, of which the Black River forms part, returned unacceptable levels of E.coli almost 80% of the time over the last five year period.

Other highly polluted rivers of concern highlighted in the report are the Big and Little Lotus Rivers which flow into Zeekoevlei, the Eerste and Kuils River catchment which flows into False Bay at Macassar, The Sir Lowry’s Pass River and Soet system, and the Hout Bay River.

60% of all rivers also have unacceptably high nutrient levels.

The recreational areas at Zandvlei are often packed with visitors on weekends and public holidays. Residents, concerned about pollution from frequent sewage spills have started a petition to “save” the vlei. Photo: Steve Kretzmann

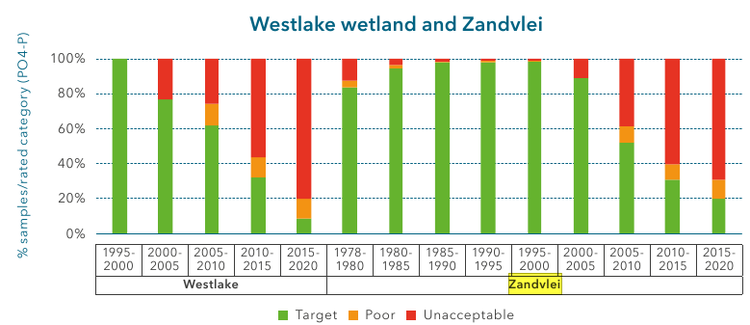

Phosphorous levels at Westlake and Zandvlei. The report states: “Phosphorus enrichment: Over time, a gradually increasing proportion of samples from rivers in the Sand catchment have been in poor and unacceptable ranges for phosphate concentration. A number of vleis in the catchment are similarly affected by gradually increasing phosphorus enrichment, which tends to encourage aquatic plant and algal growth.”

The state of the vleis and estuaries

Cape Town’s vleis and estuaries are popular for recreation. But most of our vleis and estuaries are hypertrophic, which means they are prone to toxic blooms of blue-green algae.

This is especially true of the most popular vleis and estuaries: Rietvlei in Milnerton, Zandvlei in Muizenberg, and Zeekoevlei adjacent to Grassy Park. These are also all the sites of sailing or rowing clubs.

The vleis do not seem to normally have high levels of E.coli – though Mayco member for Environment Marian Nieuwoudt confirmed that Zandvlei, for instance, was closed or partially closed for a total of 42 days in 2019 due to sewage spills flowing into the vlei. (E.coli is killed by sunlight shining on these relatively stationary bodies of water.)

“Of the five main recreational vleis/waterbodies, most have generally been in a condition conducive to intermediate-contact recreation over the past five years,” states the report. “However, Milnerton Lagoon has been subject to periodic and, at times, prolonged E. coli contamination, which suggests exposure to untreated sewage.” The lagoon, which is an estuary formed by the Diep River before it flows into the ocean, has become so polluted the Green Scorpions have ordered the City to clean it up.

But the phosphate levels are of concern. The report reveals that over 90% of all water quality tests in Rietvlei over the 2015 to 2020 period showed unacceptable phosphate levels. For Zandvlei and Westlake wetland, phosphate levels were unacceptable in 70% of all tests over the same period, and the Edith Stephens detention pond, Rondevlei and Zeekoevlei showed unacceptable levels of phosphates in over 95% of all tests over the 2015 to 2020 period.

The increasing nutrient levels over the last 30 years resulted in a toxic algal bloom in Rietvlei in November 2019, causing the City to close it for a week. Before that, Nieuwoudt confirmed, Rietvlei was also closed from March to June 2017 due to an algal bloom.

Causes of pollution

“One of the most profound impacts on water quality in Cape Town, as in many other cities, is that of waste. Treated and untreated sewage has a particularly harmful effect on our watercourses,” states the report.

Data from the national Department of Water and Sanitation’s Integrated Regulatory Information System (IRIS) dashboard, reveals Cape Town’s wastewater treatment works fail to consistently purify wastewater to minimum standards.

The Athlone wastewater treatment works, which released effluent into the Black River, achieved the minimum standard for microbiological compliance (levels of E.coli in the treated water) less than 27% of the time in 2020. Similarly, the Mitchell’s Plain wastewater treatment works achieved a microbiological compliance score of just over 29% for the effluent it released into the environment during 2020.

Other factors contributing to water pollution are informal settlements, particularly those on land unsuitable for housing where the City is unable to provide basic services. This results in residents disposing their grey water and sewage directly into the environment.

Sewer leaks and overflows are another pollution source. Xanthea Limberg, the Mayco Member responsible for water, has previously stated these number up to 400 per day across the metro, resulting in sewage flowing into the environment.

The report states that 76% of these sewer spills and overflows are caused by illegal dumping of foreign objects and fats into the sewer system, causing blockages. The remaining 24% of cases are due to the condition of the sewage infrastructure.

Further causes mentioned in the report are: overflows from sewage pump stations when these break down or, in some cases, when load shedding occurs; illegal residential or industrial connections into the storm water system; and illegal dumping.

The report also raises concern about water bodies that are not tested: “It is of some concern that there are areas in Cape Town where residents (including children) use rivers, vleis and other wetlands other than those considered in this report, for informal playing, swimming, paddling and possibly even washing, cooking and water drinking, without knowing whether the water is fit for use. Some of these waterbodies are highly contaminated. This issue can only be addressed by improving the condition of the catchments draining into these systems, through the provision of basic sanitation and servicing.”

The water flowing out of the Diep River catchment, which forms the Milnerton Lagoon, has become so polluted that the Green Scorpions have ordered the City of Cape Town to institute a clean-up plan or face criminal litigation. Photo: Steve Kretzmann

What the City is doing

The City’s response, as stated in the report, is to rehabilitate and restore Cape Town’s water bodies in line with the City’s commitment to be a water-sensitive city by 2040. Accordingly, it has established the Water Quality Improvement Programme which aims to improve “ambient water quality”.

Examples of actions to be taken are:

- capital improvements at wastewater treatment works;

- repairs and maintenance of sewage pump stations;

- informal settlements servicing;

- litter-boom project partnerships;

- engagement with catchment forums and other interest groups;

- water quality reporting;

- by-law enforcement blitzes; and

- awareness campaigns such as “Bin It, Don’t Block It”.

Responding to questions on the City’s water and waste capital expenditure budget, Councillor Limberg said R225 million had been budgeted in the 2020-21 financial year for upgrades to pumpstations and wastewater treatment plants. This is close to double the actual expenditure of R125 million during the 2019-2020 financial year.

An additional R7 million for stormwater system upgrades had been budgeted, down from R19 million the previous year.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Next: Workers pay for CCMA services that were once free

Previous: Two communities battle Nelson Mandela Bay Municipality over housing

© 2021 GroundUp. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.

We put an invisible pixel in the article so that we can count traffic to republishers. All analytics tools are solely on our servers. We do not give our logs to any third party. Logs are deleted after two weeks. We do not use any IP address identifying information except to count regional traffic. We are solely interested in counting hits, not tracking users. If you republish, please do not delete the invisible pixel.