Call to give prisons inspectorate more powers

Sonke brings court application

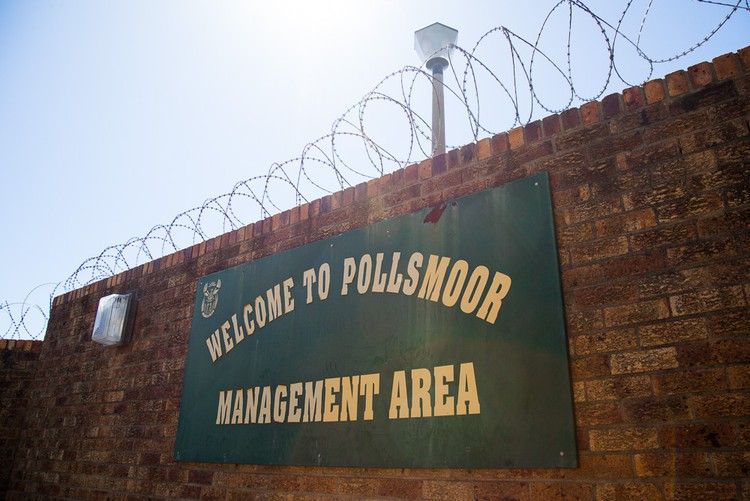

Poor prison conditions, assaults of prisoners by prison officials and a lack of accountability show the need for a more independent prisons inspectorate, says Sonke Gender Justice in papers before the Western Cape High Court.

In an application filed on its behalf by Lawyers for Human Rights, Sonke says that the Judicial Inspectorate for Correctional Services (JICS) has failed to fulfil its constitutional purpose, and that the lack of independent oversight of prisons has allowed prison officials to violate the constitutional rights of prisoners with impunity.

Sonke says the provisions of the Correctional Services Act, 1998, which establish the inspectorate, are unconstitutional because these provisions do not create a sufficiently independent inspectorate.

The chief responsibility of the inspectorate is to report to Parliament annually on the conditions and treatment of prisoners and on any corrupt or dishonest practices in prisons.

But Sonke argues that the inspectorate’s constitutional mandate is not just to report but also to hold government accountable for violations, and that the inspectorate lacks the structural and financial independence, and the legal powers, needed for this.

The head of the inspectorate, referred to as the Inspecting Judge, is a retired judge who is appointed by the President. The current Inspecting Judge is former Constitutional Court Justice Johann van der Westhuizen. The Inspecting judge has to report on conditions but the task of inspecting prisons largely falls to Independent Correctional Centre Visitors.

These visitors are responsible for recording and monitoring complaints from inmates and their resolution through the internal hierarchy of each prison. Visitors have unique access to prisons and to prison records and documents. However, Sonke argues, that the purpose of this access has been restricted to reporting and inspecting. No one in the inspectorate, including the Inspecting Judge, has the power to take disciplinary action or to make binding recommendations. In addition, the Inspecting Judge is not empowered to report offences or corruption to another body, such as the National Prosecuting Authority, for further investigation and action.

This is different from other institutions like the office of the Public Protector, and the Human Rights Commission, which are independent of government and able to take remedial steps following any investigations they conduct.

Sonke also points to problems with the independence of the inspectorate. The CEO of the inspectorate, responsible for finance and administration, is appointed by the National Commissioner of Correctional Services and is accountable to the Commissioner, not to the Inspecting Judge. Independent Correctional Centre Visitors are appointed by the CEO. In addition, the inspectorate is entirely funded by – and therefore reliant on - the Department of Correctional Services.

Sonke is arguing that the current structure of the JICS falls short of requirements for independence set down in a previous ruling by the Constitutional Court.

The court papers list difficulties the inspectorate has faced as a result of its lack of financial independence and reliance on the Department of Correctional Services for funding. This point is driven home by the table below (taken from Sonke’s founding affidavit) which compares funding of the Public Protector and Human Rights Commission to that of the inspectorate.

| Year |

JICS |

Public Protector |

SAHRC |

IPID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2012/2013 |

R31,832,500 |

R183,626,000 |

R101,500,000 |

R197,898,000 |

|

2013/2014 |

R31,666,600 |

R199,253,000 |

R119,300,000 |

R217,000,000 |

|

2014/2015 |

R45,368,000 |

R218,158,000 |

R128,100,000 |

R235,000,000 |

|

2015/2016 |

R48,370,000 |

R246,067,000 |

R144,300,000 |

R234,781,000 |

JICS operates on a budget that is a fraction of that of other Chapter 9 Institutions but is required to meet the same kind of constitutional mandate.

However, this is only part of the picture. Sonke’s affidavit contains statistics on the number of assaults of prisoners by guards and resulting convictions, as presented to Parliament by the Minister of Justice and Correctional Services.

|

Year |

Reported Assaults |

Convictions |

% Convicted |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2011/2012 |

609 |

6 |

0.99% |

|

2012/2013 |

943 |

10 |

1.06% |

|

2013/2014 |

1298 |

19 |

1.46% |

Sonke argues that these figures indicate the inspectorate’s failure to fulfil its constitutional purpose. This is, at least partly, because the inspectorate has to rely on cooperation from the Department of Correctional Services, since it does not have the power to take disciplinary steps.

The facts of this application show that the need for an independent Inspectorate is not merely theoretical. Prisoners within the South African correctional system are particularly vulnerable. As Sonke argues in its papers, prisons are ‘closed worlds’ and require effective independent oversight so that the government’s obligations under the Constitution – and international law – are met.

Failure to provide sufficiently independent oversight of prisons has allowed prison officials to violate the constitutional rights of prisoners with impunity.

The Minister of Justice and Correctional Services, the Minister of Finance, the Commissioner and the Inspecting Judge all intend to oppose the application. Sonke has given them additional time, until 28 February, to file their papers. A court date for the hearing has not yet been set.

This article has been corrected to reflect the fact that the matter is being heard in the Western Cape High Court, not the Constitutional Court as first stated.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Next: Taxi drivers told: respect women passengers

Previous: Mdantsane schools face closure, leaving learners stranded

© 2017 GroundUp.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.