Why wage inequality matters

New legislation empowers shareholders to limit outrageous CEO remuneration

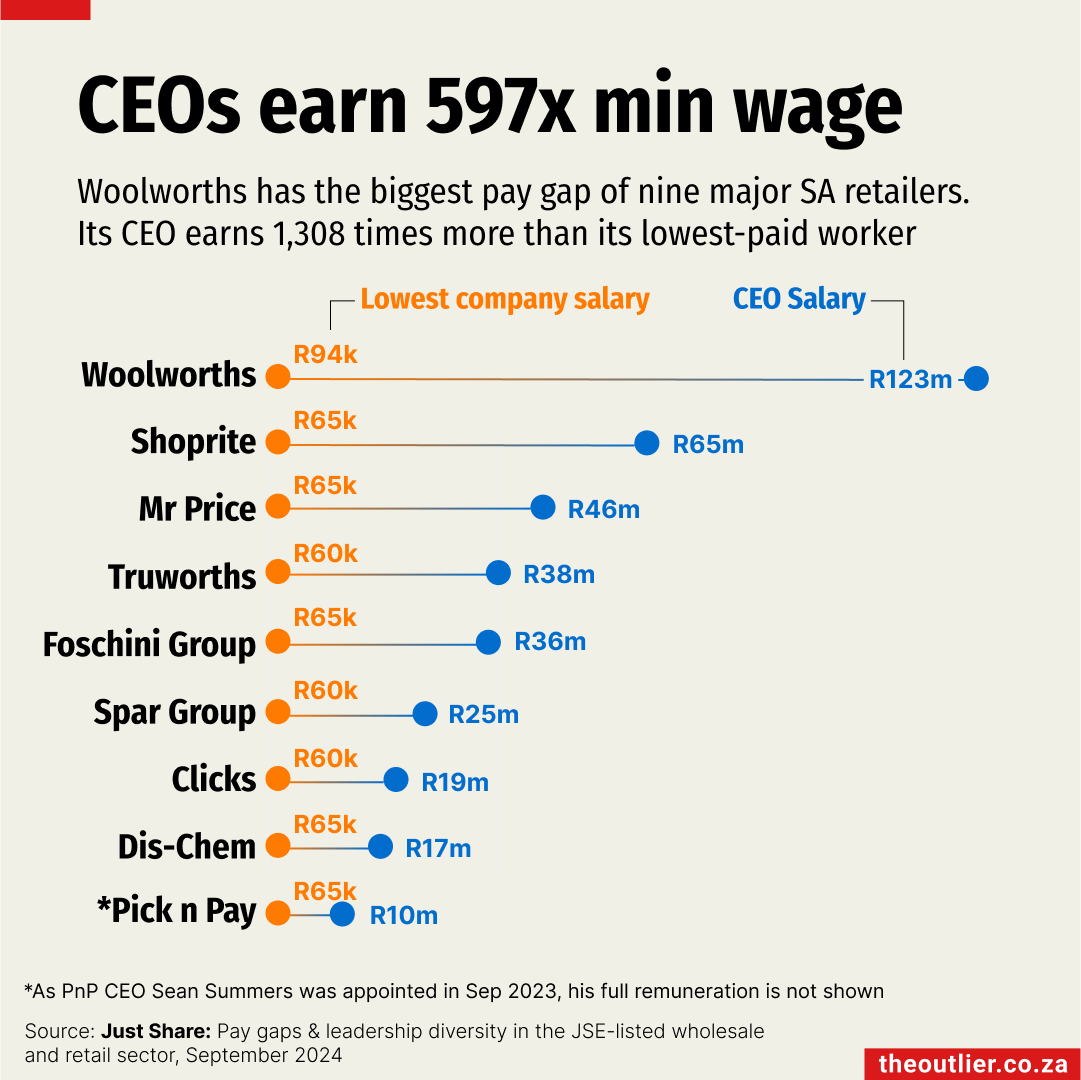

Wage inequality in top ten South African retailers. Graphic: The Outlier using data from Just Share

The late Martin Wittenberg, an econometrics professor at the University of Cape Town, had a brilliant way of portraying inequality in South Africa. He used a graphic of people, with height representing income. He cast himself as an “average” person, 1.8 metres tall, representing “average” income. The graphic showed a line of people, the population of South Africa, walking past him over the span of one hour. One minute and 650,000 people later, the people were barely the size of his ankles. Thirty minutes in, halfway, people reached his thighs. Only in the last 15 minutes do people reach his “average” height, and in the last few minutes, we see people the size of buildings, and, finally, taller than Table Mountain.

South Africa is the most unequal country in the world, according to the World Bank. Even worse, while developing countries have managed to reduce inequality on average, South Africa has not.

In 1998 the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) report highlighted the widening gap between the rich and poor as a “disturbing legacy of the past”, which democratic processes have failed to mitigate. The report warned that allowing this inequality to continue is “morally reprehensible, politically dangerous, and economically unsound”, and emphasised that business must play a significant role in addressing this inequality.

More than three decades into democracy, the legacy of income inequality endures. The 2019 Stats SA Inequality Trends Report, published 21 years after the TRC report, makes it clear that little progress has been made correcting the imbalance within the labour market. The report finds that negative real earnings growth for low and median earners, combined with skyrocketing pay at the top, drives South Africa’s increasing income divide.

In 2024, the situation has not improved. Just Share recently looked at the ten biggest publicly-listed companies in the wholesale and retail sector, and found that the average CEO in this sector earns 597 times what the lowest paid worker earns. In other words, the average entry-level employee in the wholesale and retail sector would need to work for 21 months to earn what an average CEO in this sector earns in one day. CEO pay is absurdly high in South Africa, especially in the banking and mining sectors.

To justify these extreme salaries, companies invoke “market forces”, particularly the supposed scarcity of top executive talent. Remuneration committees, using consultants’ benchmarking exercises, rely on this argument to gain approval for inflated CEO packages from institutional investors, a trend not limited to the retail sector. These benchmarks create a self-perpetuating cycle where executive pay continues to rise regardless of performance or fairness.

Meanwhile, the frontline workers who are crucial to business success are left behind. The International Labour Organization (ILO) emphasises that equitable societies do not arise naturally from market forces. In other words, a just society relies on conventions and legislation to actively reduce inequality. So far in South Africa, this has meant two things: a minimum wage, and attempts at transparency. Neither has been sufficient.

The minimum wage was introduced in 2019 to protect vulnerable workers, but it has proven inadequate to lift people out of poverty or reduce inequality. It falls far short of a living wage, defined as “the remuneration received for a standard workweek that is sufficient to afford a decent standard of living for the worker and their family”.

And yet the wider economic benefits of decent pay for workers, and smaller wage gaps, are clear. At a macro level, reduced income inequality is linked to more stable and sustainable economic growth. A fairly paid workforce is more resilient and able to withstand economic shocks. Paying workers fairly provides them with more disposable income, which increases consumer spending. They rely less on social services, potentially lowering the tax burden of social grants. Workers who feel that they are fairly compensated are often more motivated and productive, and invest more in education and skills development, improving the overall quality of the workforce. Increased tax revenue can be reinvested in public services and infrastructure. Better paid workers invest more in their retirement, reducing future strain on social security systems.

Inequality is also a serious social ill. Entire books and many research papers have been written about how inequality is linked to lower trust in government, institutions, and one another, as well as with higher crime, poor health and education outcomes, and even feelings of happiness. This should not be surprising: people have a natural preference for fairness. Sociologists call it “inequity aversion”. We simply do not like to see something we perceive to be unfair, and most people would agree that a CEO earning 597 times more than the lowest-paid workers is woefully unfair.

It need not be this way. While investors have historically shown limited resolve in holding companies to account for extreme pay gaps, this may well be because shareholder votes on remuneration policies were not binding. With the recent signing into law of the Companies Amendment Act 16 of 2024, there is potential for a shift.

The Act introduces binding shareholder votes on remuneration, potentially shifting the balance of power and ensuring that boards and executives are held accountable for unjustifiable pay practices. In doing so, the Act aims to promote “the achievement of equity between directors and senior management on the one hand, and shareholders and workers on the other hand, as well as addressing public concerns regarding high levels of inequalities in society”.

When the Act comes into operation, companies will be required to disclose detailed pay information, including the total remuneration of the highest and lowest-paid employees, and the pay gap ratio between the top 5% and bottom 5% of workers. While this is a step forward, it does not account for indirectly employed or subcontracted workers, or address the gender pay gap.

While pay disparities across sectors and occupational levels are expected, the magnitude of the gaps in South Africa should raise concerns, from both an economic and moral standpoint. Workers deserve to earn enough to meet their basic needs, support their families, and live in dignity. Addressing pay gaps will contribute to a more equitable society and an inclusive economy, in which more people can participate, contribute and thrive.

Views expressed are not necessarily those of GroundUp.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Next: Durban police brutality case heads to trial after years of delays

Previous: Eviction looms for victims of traditional leader’s land scam

© 2024 GroundUp. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.

We put an invisible pixel in the article so that we can count traffic to republishers. All analytics tools are solely on our servers. We do not give our logs to any third party. Logs are deleted after two weeks. We do not use any IP address identifying information except to count regional traffic. We are solely interested in counting hits, not tracking users. If you republish, please do not delete the invisible pixel.