Court overturns ruling on worker fired for assault

Constitutional Court sets boundaries on “common purpose” rule

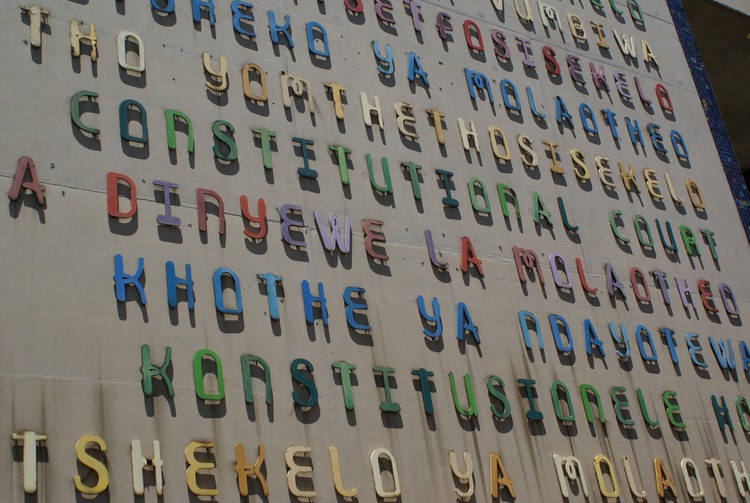

The Constitutional Court has clarified when an employer can dismiss workers who associate with violence committed by others based on the “common purpose” rule. Archive photo: Ciaran Ryan

- The Constitutional Court has clarified when an employer can dismiss workers who associate with violence committed by others based on the “common purpose” rule.

- In 2017, 12 workers brutally assaulted the head of human resources at Marley Pipe Systems.

- Under common purpose the company dismissed 148 workers, including 40 workers who could not be placed at the scene, and one worker who was not at work.

- NUMSA took the company to court for unfair dismissal, and lost in the Labour Court and the Labour Appeal Court.

- The Constitutional Court has now ruled that the conditions for common purpose were in fact not met.

On Monday, the Constitutional Court delivered an important judgment regarding when an employer can dismiss workers who associate with violence committed by others based on the “common purpose” rule.

Common purpose is a legal rule which says that when someone unlawfully associates themselves with unlawful conduct committed by others, they can be held liable in the same way as the person who actually committed the crime. For example, if a group of people commit an assault, those not directly involved in the assault could be found guilty of assault based on common purpose, if they unlawfully associated themselves with the assailants, by for example shouting words of encouragement or helping the assailants by handing them weapons to commit the crime.

Common purpose is controversial. It was often abused during apartheid to suppress opposition towards the government.

The recent Constitutional Court decision clarifies when common purpose can be used in the labour law context. According to the unanimous judgment written by Justice Mbuyiseni Madlanga, common purpose will only apply when other people unlawfully associate with the crime.

In 2017, workers belonging to the National Union of Metalworkers of SA (NUMSA) went on an unprotected strike over a wage agreement concluded in the Plastics Negotiating Forum. The striking workers were employed by Marley Pipe Systems which, among other things, produces plastic piping.

On the first day of the strike, the workers went to the canteen to address the company’s head of human resources, Ferdinand Steffans. When Steffans did not arrive, they went to the administrative offices. Some workers were carrying placards that called for Steffans’s firing.

When Steffans did appear, he was attacked by several of the workers. According to court papers, rocks were thrown at him, he was punched and kicked while on the ground, and he was thrown through a glass window.

He escaped and was assisted by two other workers who were not participating in the strike.

After the strike ended, the workers were charged with two counts of misconduct: the assault and participating in an unprotected strike.

After the hearing concluded, 148 workers were found guilty of both counts.

The company could only show that 12 workers had actually committed the assault. But the chairperson of the disciplinary hearing said that the 136 other workers were also guilty based on the common purpose rule.

A total of 95 workers could be placed on the scene of the assault through video footage and photographs. A further 40 workers could not be placed at the scene. But the company said their clock-in cards showed they were not at their workstations when the assault occurred. They were also found guilty of the assault based on common purpose and dismissed.

Another worker was also dismissed based on common purpose, even though his clock card showed that he had only arrived at work after the assault occurred.

NUMSA then referred an unfair dismissal case to the Labour Court on behalf of the 148 workers. The Labour Court dismissed the case. NUMSA then took the case on appeal to the Labour Appeal Court, but only on behalf of the 41 workers who could not be placed at the scene of the assault. The Labour Appeal Court dismissed the case.

The Labour Appeal Court said there was no evidence that the 41 workers had distanced themselves from the assault or had intervened to stop the assault. They also did not take steps to distance themselves from the assault after it happened.

NUMSA then appealed the case to the Constitutional Court.

Constitutional Court Proceedings

The Constitutional Court said that the case was important because the Labour Appeal Court had created a new rule for common purpose. The new rule was that an innocent bystander must actively take steps to prevent an assault before they can escape liability for unlawful acts done by others under the common purpose rule.

“The new principles created by the Labour Appeal Court will affect large numbers of employees, where strikes – whether protected or unprotected – turn violent,” said Justice Madlanga.

The Constitutional Court said that common purpose is often used when employers cannot directly show that individual employees committed misconduct. But, the main problem with applying common purpose too easily is that innocent employees, who were not involved or did not support the misconduct, could be found guilty and dismissed, the court said.

Justice Madlanga also said that the Labour Appeal Court was probably correct to find that the 41 workers may have been at the scene. But, there was also no evidence which positively identified them as being at the scene of the assault. There was also no evidence that they had encouraged or supported the assault. This meant that they could not be found guilty of the assault under the common purpose rule.

This was particularly important for the worker who only arrived at work after the assault occurred. While he participated in the unprotected strike, he could not have unlawfully associated with the assault.

The Labour Appeal Court was incorrect to develop a new rule for common purpose, the judge said. The workers did not have a legal duty to intervene in order to avoid being held liable for the assault under common purpose.

“At a moral level, one may have to intervene to save a fellow human being from harm. But I am not aware of any legal obligation to do so,” said Justice Madlanga.

Justice Madlanga also said that the company first had to show that the employees were at the scene of the assault and encouraged or associated with the assault before common purpose could apply. Only being at the scene of the assault, and not intervening to stop it, did not mean that the 41 workers had encouraged the assault. Nor did the fact that workers were singing and dancing necessarily mean that they were celebrating or associating with the assault.

Justice Madlanga said that while he was sympathetic to the situation employers face when violent strikes occur, this did not mean that employers could dismiss workers when there was no evidence that they associated with violence by other workers. This would mean that the law would allow innocent workers to be dismissed when they had not done anything wrong.

The Constitutional Court upheld the appeal because the requirements to hold the 41 workers liable for the assault in terms of the common purpose rule were not met.

However, the workers had still participated in an unprotected strike. The Constitutional Court said that the appropriate way forward would be to send the case back to the Labour Court to determine an appropriate sanction for their participation in the strike.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Next: NUMSA did not breach interdict by holding national congress, court rules

Previous: Teenager electrocuted in Gqeberha river

© 2022 GroundUp. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.

We put an invisible pixel in the article so that we can count traffic to republishers. All analytics tools are solely on our servers. We do not give our logs to any third party. Logs are deleted after two weeks. We do not use any IP address identifying information except to count regional traffic. We are solely interested in counting hits, not tracking users. If you republish, please do not delete the invisible pixel.