Giant turbine farm set to harvest West Coast wind

Environment minister dismisses appeals against new wind farm

Appeals against plans for a huge new wind farm on the West Coast have been dismissed by environment minister Barbara Creecy, paving the way for the addition of up to 140 megawatts of renewable energy into the national grid.

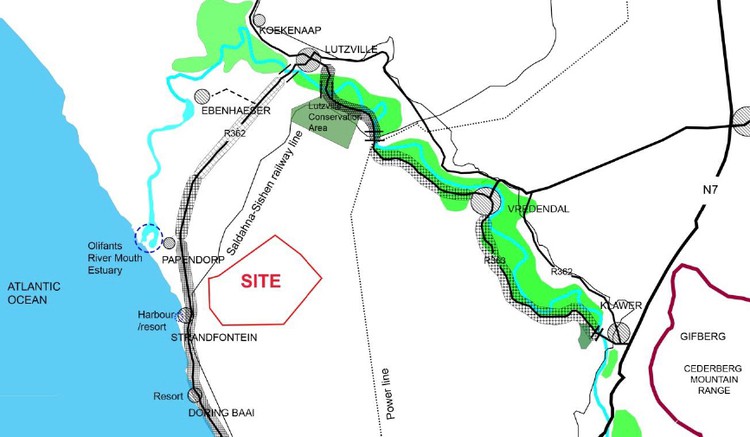

This is the Juno Wind Energy Facility, planned for a farm in the West Coast District Municipality area about five kilometres from the coast. It will consist of up to 49 turbines, some of which will stand nearly 180m high, and associated infrastructure to connect it to the Eskom national grid.

It is one of 12 wind and solar renewable energy projects currently in the planning phase within just 35km of each other in this region, according to Juno project documentation.

Some of these projects already have environmental authorisation and others are in the statutory environmental impact assessment (EIA) phase.

Although not all are likely to become operational as “preferred bidders” under REIPPP (government’s Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Programme), the proliferation of proposals indicates the important potential of this West Coast region as the renewable energy industry looks to meet government’s ambitious REIPPP target of 17,800MW of electricity by 2030. (To see this in perspective, Eskom claims its current coal-powered plant capacity is about 35,000MW, about double the 2030 renewable energy target.)

However, proposals for renewable energy facilities, and particularly wind farms, often generate tensions and strong differences of opinion among nearby communities. While many welcome such development for both economic and environmental reasons – such as new job opportunities and shifting the balance away from highly damaging fossils like coal – others are deeply concerned about biodiversity impacts on bats, birds and vegetation; visual impacts and loss of landscape; negative effects on adjacent residential property prices; and whether assessments of these major projects by specialists and environmental practitioners are genuinely neutral and unbiased.

The two appeals against the Juno project approval highlight some of these concerns.

The first appeal was from the ratepayers’ association of the seaside holiday village of Strandfontein. The closest turbine will be just 3.6km from the nearest house in the village that has about 120 permanent residents, although the final layout of the turbines is still to be determined in a process that must include further public consultation.

The wind farm will also be quite close to the small historic West Coast settlements of Ebenhaeser, Doringbaai and Papendorp, and the town of Lutzville.

According to a social impact assessment undertaken as part of the statutory assessment of the proposed project, development of Juno will create 136 jobs and local business opportunities during both the construction and operational phases of the project, while the establishment of a Community Trust will also benefit local residents.

“In this regard the establishment of renewable energy projects in the area, including in the proposed Juno [wind farm], is supported by the Ebenhaeser Communal Property Association, Doringbaai Development Trust and Matzikama Local Municipality.

“The proposed development also represents an investment in clean, renewable energy infrastructure, which, given the negative environmental and socio-economic impacts associated with a coal based energy economy and the challenges created by climate change, represents a significant positive social benefit for society as a whole,” the executive summary of the Final Environmental Impact Assessment report states.

According to the social impact report, potential negative impacts will be largely confined to Strandfontein and are linked to visual impacts and the associated effect on the area’s sense of place, property values and tourism. While half of the properties in the village would be visually impacted by the wind farm, based on the findings of a literature review, the potential impact on property values and tourism was “likely to be negligible” – less than two percent.

But this finding is one of many challenges raised in the Strandfontein ratepayers’ association’s appeal. It pointed out that property valuation data on which this finding was based had been drawn from other areas and was not representative of the reality of their village

The association also argued strongly that assessments by specialists in the EIA process were biased and many of their findings “deeply flawed” and based on incorrect information. It wanted these reports to be independently reviewed.

It also argued that the public participation process had been “hopelessly inadequate”, particularly because interested and affected parties had included rural and historically disadvantaged communities. The process should have been facilitated by, among others, an announcement of public meetings on local radio stations, sucha as Radio Namakwa, in local languages and by holding such public meetings at appropriate times.

In her appeal decision, Creecy dismissed the association’s concerns, saying she was satisfied that the public participation process had been conducted appropriately. There was evidence that the wind farm project was supported by representatives of the Ebenhaeser Communal Property Association, the Papendorp community and the Doringbaai Development Trust, and her department had “considered, evaluated and assessed all relevant information” in making its decision to authorise the proposed wind farm.

The second appeal was by the provincial heritage agency, Heritage Western Cape (HWC).

The agency initially refused to accept the findings of visual and heritage assessments that impacts would be minimal and of low significance, saying key information was missing.

The developer — Cape Town-based company AMDA Juliett (Pty) Ltd, a special purpose vehicle created by Spanish renewable energy and sustainability specialist AMDA energía — then appointed three local independent heritage experts to consider HWC’s concerns. But they found no evidence of any “fatal flaw” in the project from a heritage point of view, and said the visual impact of the proposed wind farm on the character of the landscape would be minimal.

After receiving these supplementary reports, the heritage agency withdrew its appeal, but, bizarrely, appeared not to have informed Creecy’s department of this decision.

HWC did not acknowledge or respond to GroundUp’s request for comment.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Next: Covid-19 relief can be aligned to BEE, court rules

Previous: Pressing need for food parcels in Durban

Letters

Dear Editor

It's bizarre that such a project is allowed to proceed.

The amount of fossil fuels used to create, install, maintain, and eventually dispose of these wind turbines, totally negates the energy generated. To solve things like these, we need lawmakers who specialise in both law and ecology and maybe ethics, since it appears that these current judges have no clue as to the effects of non-biodegradable materials on the environment.

Either that, or it's yet another case of greed and corruption. Let's all check back in 10-15 years to see what's happened to the land at these sites.

© 2020 GroundUp.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.