Heroin use has spread as prices plummet

South Africa’s central position in a drug smuggling route between West Asia and Europe plays a role

A close-up of an opium poppy in Afghanistan. Photo: United Nations via Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

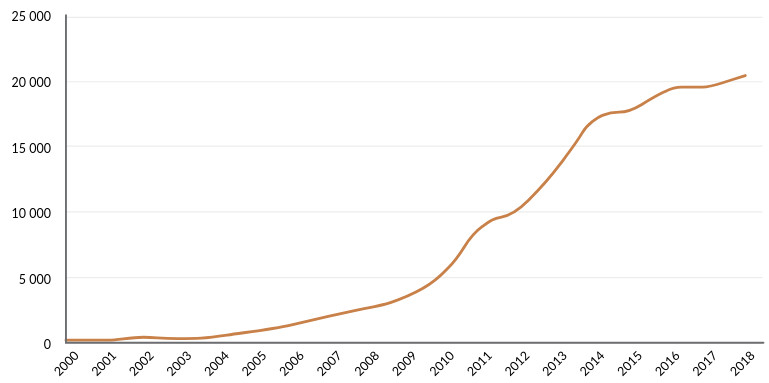

- The volume of heroin seized by the South African police has been increasing. First slowly since the late 1990s, and then ramping up from about 2013.

- The increase is partly driven by a change in international drug trafficking routes, with South Africa being used to get the drug from Afghanistan to markets in Europe.

- While heroin was once mainly used in Hillbrow, the increase in supply has caused prices to plummet, making it more widely available across the country.

- Of the many people who try heroin, some eventually become addicted. Addiction is usually a consequence of complex social reasons, including experiences of trauma.

The street price of heroin has fallen dramatically over the last two decades in South Africa, leading to a proliferation of cheap heroin markets across the country.

Back in 2004, heroin cost about R215 a gram in Cape Town. A recent study showed that in 2020, it was just R123 on average in the same city. If we factor in inflation over this period, then this means that the real price of the drug is about a quarter what it was in 2004. (A gram is typically about three or four hits or highs for injecting users.)

This sharp decline in price has gone hand in hand with a large increase in heroin use over a similar period.

Most registered rehabilitation centres are monitored by the SACENDU project, which is run by the South African Medical Research Council. Back in 2006, only 6% of people who were admitted to SACENDU-linked rehabs were there because of opiates (a class of drug which includes heroin). By 2023, that figure had tripled to 17% according to Jodilee Erasmus, a scientist at SACENDU. Most opiate-related admissions are caused by heroin, she says.

Annual police cases linked to heroin shot up over a similar time frame, as did the share of medical scheme members seeking treatment for opioid use disorder.

By 2020 there were an estimated 400,000 people using heroin daily across South Africa. Nigeria, which is one of the only other African countries to have data on national drug use, has fewer than 90,000 users, though it has a much larger population.

Treatment centres find that most users in South Africa smoke the drug, though a large minority also inject it. In many cases, people transition from smoking to injecting, which allows the drug to go straight into the bloodstream, delivering a more potent high.

Europe’s drug markets and South Africa

In the 1990s, the domestic heroin market was primarily concentrated among white people in Hillbrow. However, as the drug got cheaper it began to proliferate across poor rural settlements and urban townships, where it is known locally as nyaope.

(Nyaope is commonly reported to be a unique substance made of various ingredients, but a recent laboratory analysis of the drug found that it is mostly high-grade heroin.)

Why did the market change? Much of this has to do with South Africa’s changing role in global smuggling networks.

Heroin is made from the opium poppy plant. The plant is typically cultivated in Afghanistan and then refined into heroin in neighbouring Pakistan. To get the drug from there to consumers in Europe, smugglers have traditionally driven it across Pakistan’s border into Iran, onward to Turkey, and then into Greece or Bulgaria.

But in 2015, the United Nations published a report which stated that drug syndicates had been pivoting away from this land route. Instead, they were increasingly using ships to transport the drug along a variety of different channels (collectively known as the “southern route”).

A report by Enact highlighted one of the pathways along the southern route, which is to ship the drug along the Indian Ocean to east African countries like Tanzania or Mozambique, and then drive it down to South Africa. From there it’s re-exported to Europe either via boat or plane (something which is made easier by South Africa’s extensive trade connections with Europe).

Police cases involving heroin in South Africa from 2000 to 2018. Source: Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime

Central nodes in this smuggling network include the harbours in Durban and Cape Town, a dry port in Johannesburg called City Deep, as well as OR Tambo airport.

While interviews with people in the criminal trade suggest that the southern route became more popular from as far back as the mid-1990s, police seizures of heroin in eastern Africa only shot up from around 2010, which is roughly when the European Union Drugs Agency says the route became more important.

In South Africa, this spike in heroin seizures happened a little later, from about 2013, though there had been incremental growth since the late 1990s.

As the volume of heroin transiting through eastern and southern Africa escalated, drug syndicates found it increasingly profitable to develop spin-off markets for local consumption, making the drug more widely available and affordable throughout the region.

Not everyone gets hooked

The supply of cheap heroin only tells part of the story. It doesn’t tell us why so many South Africans have been drawn to the drug in the first place. A popular explanation is “peer pressure”.

“Usually, a person will pinpoint peer pressure to say this is what got me started [on heroin]”, says Xikombiso Valoyi, a social worker at the Community Oriented Substance Use Program (COSUP) in Tshwane. The reason, he says, is that “they had friends with them when they started”.

However the explanation is incomplete, he says, because “the real question becomes ‘why did they stay?’”

Valoyi, who works with drug users across several Tshwane townships, notes that in contrast to what is often believed, many people who try heroin don’t continue using it. A group of friends who start experimenting with the drug (often in their teenage years) slowly withers down to one or two people over time, he says.

There are several reasons why these remaining people may continue using, but Valoyi notes that psychological stress often plays a role. “It’s as if the problems and traumas that they have - the things that were in their minds for a long time - cool down [when they take heroin],” he says.

The result is that “they keep going back to this one source of calmness and quiet,” says Valoyi. “It becomes like medication.”

Indeed, a study published earlier this year found that people who recently used illicit drugs in South Africa were more likely to have experienced traumatic events like intimate partner violence.

Alongside the psychological dimension, those who continue to use heroin also become increasingly physically dependent over time. For some heroin users, withdrawal can kick in just a few hours after their last dose. Symptoms can include muscle cramps, fatigue and difficulty sleeping. This means they need to take the drug several times a day to cope.

While it’s often assumed that such people spend their days lazing about or stealing, research in Durban’s townships shows that heroin users on the street often have to work hard to ensure that they can buy multiple doses a day. This work often includes collecting and selling scrap metal, washing cars and cleaning yards.

As one heroin user told the researchers in Durban: “If someone wants work done they ask us … They know that we are cheap because we always want money to smoke [heroin].”

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Next: Women dig their own pipeline after years of frustration with eThekwini water supply

Previous: In this village some people say they drink just one cup of water a day

© 2024 GroundUp. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.

We put an invisible pixel in the article so that we can count traffic to republishers. All analytics tools are solely on our servers. We do not give our logs to any third party. Logs are deleted after two weeks. We do not use any IP address identifying information except to count regional traffic. We are solely interested in counting hits, not tracking users. If you republish, please do not delete the invisible pixel.