How a slave from Mauritius led a rebellion in Cape Town

And how he was influenced by a revolution in Haiti

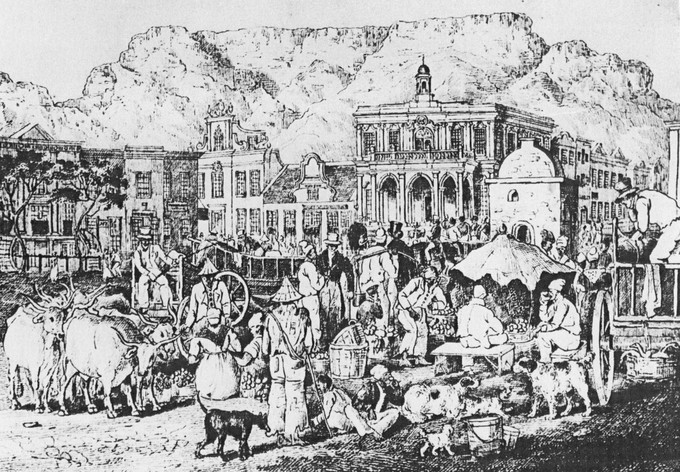

On 27 October 1808, about 340 slaves from the Swartland and Koeberg hinterland of Cape Town rose up in revolt. They attacked over thirty of the prosperous grain farms of the region, took the farmers prisoner and marched on Cape Town where they planned to ‘hoist the bloody flag and fight themselves free.’

The uprising was short-lived. On reaching Salt River, the slaves were met by troops sent out from the strongly-guarded Castle and were swiftly overcome. Within 36 hours it was all over. Because of this the uprising is not today widely known about or remembered.

Yet it was a highly significant event. Throughout the preceding 150 years of slavery at the Cape slaves had often resisted their owners. This was both by overt attacks on individuals or their property – fields and vineyards waiting to be harvested often went up in flames – as well as by less obvious means such as working slowly, breaking equipment or poisoning food. But usually slaves then ran away, seeking to escape from the colony into the interior.

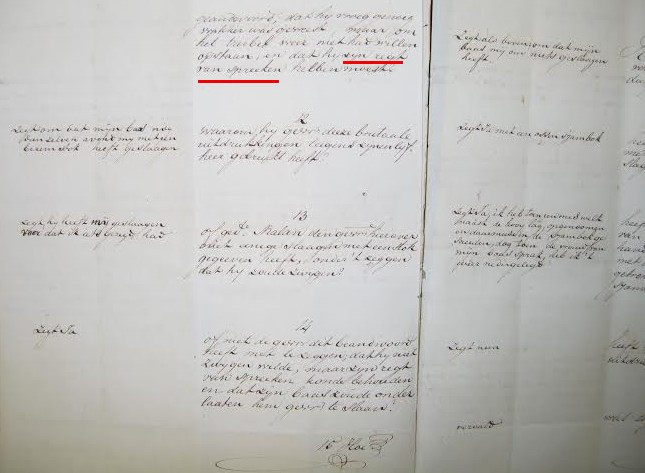

But by the end of the eighteenth century, there was a new sense of resentment amongst Cape slaves. They were influenced by the revolutionary events in France and America, and in particular by the massive and successful slave revolt in Haiti. Instead of running away, Cape slaves were now beginning to demand their ‘rights’ and to stand up to their owners. For example in 1793 the slave Cesar van Madagascar was reprimanded by his owner for getting up late. He replied, “I was awake early enough, but because the weather was bad, I did not want to get up, and I must have my right to speak”.

In 1808 the slaves’ demand for change took a new turn. They went from farm to farm, gathering support from slaves and from some of the Khoi labourers as they went. They were armed with guns and greatly outnumbered the farmers, many of whom were taken by surprise. They took over the farmsteads, captured their owners and demanded freedom for all slaves and ‘to make themselves masters.’ This was a revolutionary act.

An intriguing aspect of the 1808 uprising is how the rebels behaved on the farms. There was very little direct physical violence. Instead they asserted themselves by deliberately reversing the roles of slaves and masters, often in highly symbolic ways. They gave orders to the male farmers and overseers while holding sjamboks, the symbol of the slave owner. They hunted down on horseback and with the help of dogs those farmers who attempted to escape, forcing those they captured to run in front of their horses. This was exactly how slave runaways were caught. They deliberately addressed the farmers with the familiar word jij rather than the respectful u expected of a slave addressing his owner. They demanded that the farmers doff their hats to them. They insisted on being given wine from the cellars in the best glasses. They told the slaves they met on each farm to stop treating their owners with respect since ‘their time is up’.

At the first farm they visited, the rebel leaders carried out an elaborate charade. They pretended to be visiting ship captains, and were served dinner and wine by the unsuspecting farmer’s wife while others informed the farm slaves what was afoot and obtained their support.

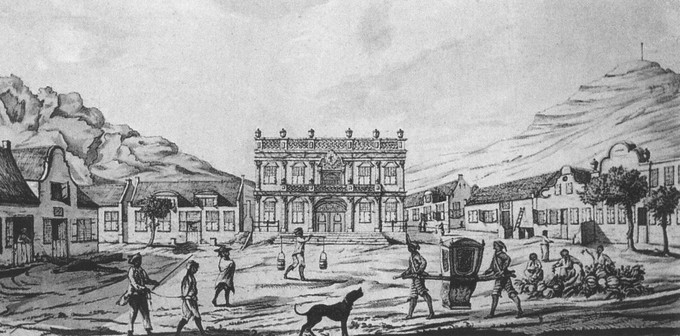

The leader of the revolt was a Cape Town slave named Louis. He had been transported to the Cape from Mauritius when he was a young boy. Now in his early 20s, he was owned by the proprietor of a wine store on the foreshore where he mingled with the diverse and transient population of sailors and soldiers from throughout the Atlantic and Indian Ocean worlds. They brought news of the momentous events taking place in this era of revolutions and war, including the slave uprising in Haiti.

Louis was particularly incensed when he met two Irish soldiers who told him that there was no slavery in Europe or America. As he later said, ‘I had heard that in other countries all persons were free, and there were so many black people here who could also be free, and that we ought to fight for our freedom.’

A clue of what inspired Louis is that he took particular care to obtain special clothes to wear : ‘a blue jacket turned up with red, white Chinese linen trousers … two golden and two silver epaulets besides some feathers for his hat.’ This was exactly the uniform worn by the the Haitian slave leader Toussaint l’Ouverture as shown in a print of the time. It seems clear that Louis was imitating the slave hero Toussaint.

But Louis did not have Toussaint’s success. His rebellion was swiftly crushed and he was sentenced to death. The slaves had only tasted power for a short time. Nonetheless their world would never be quite the same again. In the subsequent years more and more Cape slaves demanded rights within the colony rather than running away. This, as much as the actions of distant abolitionists, was eventually to bring chattel slavery to an end in the 1830s.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Next: Don’t blame apartheid for our problems, struggle hero tells government

Previous: Lessons in state capture from the Broederbond scandal

© 2016 GroundUp.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.