Joburg’s water woes are self-inflicted

The temporary shutdown of the supply from Lesotho is not the problem

Katse Dam in Lesotho is the largest of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project reservoirs, with a storage capacity of nearly 2-billion cubic metres. (Exclusive copyright David Southwood. Used with permission.)

- There is sufficient water for Johannesburg’s needs despite fears around the maintenance shutdown of the supply from Lesotho.

- The Vaal Dam has half the water it had this time last year, but this is not unprecedented and the Sterkfontein Dam which has as much capacity is full.

- The water currently in the Sterkfontein Dam is enough to meet the demands of Joburg and surrounds for almost two years, according to an expert.

- However, Joburg is using more water than is wise and high consumption needs to be addressed.

- And another dam of similar capacity is planned to come on stream in 2028.

At midnight on 30 September, large gates were closed at two points along the Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP), marking the beginning of a six-month maintenance shutdown, the longest in its 20-year history.

The stoppage comes amidst ongoing water provision issues in South Africa’s urban highveld, which draws water from the LHWP via the Vaal Dam. Johannesburg’s water provision problems have been linked to poor management of water infrastructure by municipalities, but in advance of the LHWP shut down, some analysts warned that the stoppage could exacerbate these problems.

But water management specialist Carin Bosman disagrees.

“An increasing number of people, including some who should know better, appear to believe that the planned shutdown of the LHWP will contribute to the water supply problems experienced in Johannesburg, but these aspects are in fact unrelated,” says Bosman.

The fact that the level of the Vaal Dam stood at 41% percent of capacity last week compared to 80% this time last year, “isn’t helping to dispel notions that we are facing water shortages,” says Bosman, who worked for the department of water before and after the advent of democracy.

She says, “It is not unusual for the level of the Vaal Dam to be around 40% at the end of the dry season. There is a difference between a meteorological drought, which is the result of rain not falling in the rainy season, and an institutional drought, which is the consequence of water management failures. Johannesburg is suffering from the latter.”

Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS) spokesperson Mandla Mathebula said the Sterkfontein Dam, on the edge of the Drakensberg escarpment, functions as a reserve dam for the Vaal Dam. Sterkfontein Dam has a similar storage capacity to that of the Vaal Dam, but according to Mathebula, “it is a deeper dam, and the environment is cooler, so it doesn’t lose as much water by evaporation”.

“The standard operating rule is that Sterkfontein Dam releases water to the Vaal Dam when the Vaal Dam reaches a level below 18%. The Sterkfontein Dam is currently full [98%] and will be used to top up the Vaal Dam should the need arise,” said Mathebula.

Richard Holden, a water and sanitation expert, put it more starkly: “Sterkfontein has a capacity of over 2,600-million cubic metres, which on its own is enough to meet the demands of Johannesburg and surrounding areas for almost two years,” he said.

But Johannesburg is using more water than is wise. Rand Water, which supplies bulk water to Gauteng Province, has exceeded the volume of water it is licensed to provide to Gauteng’s municipalities every year for the past six years. The utility is licensed to supply the province with 1,600-million cubic metres a year, but exceeded this by 193 million cubic metres in 2023/2024.

In a June speech to the Strategic Water Partners Network, DWS director general Sean Phillips warned, “It would be irresponsible to allow [Rand Water] to abstract more. If we had a drought, this could mean a day zero situation in Gauteng.”

The term Day Zero – referring to the day on which municipal water would be largely shut off due to supply shortages – was used by Western Cape authorities during the water crisis of 2015-2020 to galvanise people to use water sparingly. There is no official Day Zero campaign for Johannesburg but the term has been seized on by some.

“Some unscrupulous scaremongers are using it to sell water storage tanks, and it is increasingly present in media headlines, which is unfortunate because Johannesburg is not facing Day Zero,” said Bosman.

“It is important that people become more water wise and the department faces a delicate balancing act of putting pressure on citizens and local water authorities to change their ways, on the one hand, and on the other to avoid creating the impression that there isn’t enough water around to meet needs.”

And then there is the huge problem that nearly half of Johannesburg’s water is lost to leaks. We will be writing more about this in a future article.

At nearly 2,000 metres above sea level the Lesotho Highlands Water Project’s Katse dam is the highest elevation dam in Africa, with the second highest wall at 185 metres. (Exclusive copyright David Southwood. Used with permission.)

How Johannesburg gets its water

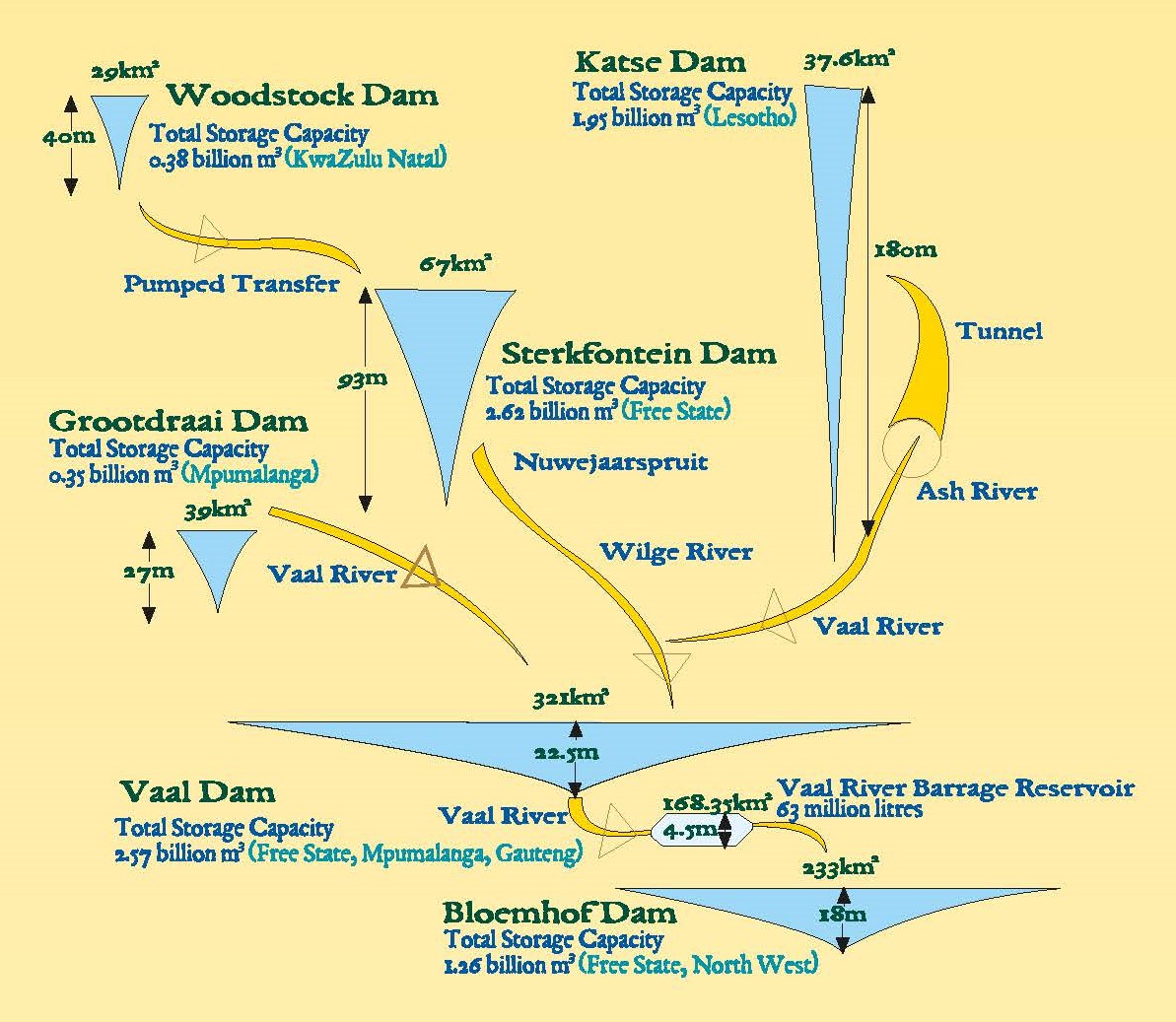

Mathebula explained that Johannesburg receives water from the Integrated Vaal River System (IVRS), a network of fourteen dams that are linked to each other by a system of rivers, canals, tunnels, pipelines and pump stations, and which together store over 9,300-million m3 of water.

“The Vaal Dam is the most important impoundment in that system because it is from here that Rand Water abstracts water for treatment, but it is only one part of the very big system that the DWS manages, in which water can be transferred from one part of the system to another, as and when required,” he said.

According to Johan Tempelhoff, Professor of History at North West University, the complexity of the IVRS is a consequence of the fact that Johannesburg was built on a watershed.

“Several streams come off the watershed and there are some good springs in the area, but their ability to meet the rapidly growing city’s needs had been exceeded as early as the drought of 1895,” he said.

To solve the problem, the government looked to the waters of the distant Vaal river, completing an impoundment called the Vaal Barrage in 1923, and the much larger Vaal dam in 1938. Today, all of Johannesburg’s treated water comes from the Vaal dam.

“It wasn’t long before the water that naturally enters the Vaal dam was not sufficient to meet the demands of the industrialising highveld. It was for this reason that two major “inter-basin” water transfer schemes were developed, capable of feeding water into the Vaal’s main feeder rivers from catchments hundreds of kilometres to the south,” Tempelhoff said.

The first of the inter-basin schemes to be completed, in 1974, was the Thukela-Vaal Transfer Scheme, which is fed from Mont-Aux-Sources atop the Drakensberg escarpment.

According to Holden, “Water from the Thukela River enters Woodstock Dam, and some of this is ultimately pumped over the Drakensberg into Driekloof Dam for use in the Drakensberg Pumped Storage Scheme. When Driekloof is full, the excess water enters Sterkfontein Dam, and it is stored here until it is needed in the Vaal River System,” he said. The DWS does not release water from Sterkfontein until it is absolutely necessary.

“The fact that it is pumped water means that it is expensive water, so it is kept up there for emergency use only,” he said.

The other scheme is the LHWP, which impounds the water from several catchments in Lesotho in two large reservoirs called Mohale and Katse.

Water released from these reservoirs is gravitated through a series of pipes and tunnels into South Africa’s Ash River, which flows into Liebenbergsvlei, which joins the Wilge River, that discharges into the Vaal dam.

Holden chuckled when asked if the LHWP was the biggest supplier of water to the Vaal dam.

“We don’t operate the system that way,” he said. “Some parts of that system will always be compensating for other parts. That’s just the nature of the water cycle.”

He gave the example of 2015, a year in which, during a drought in Lesotho, “the flow of water from Lesotho was significantly reduced without impacting on the assurance of supply”.

Holden said that LHWP is, however, the most consistent provider of water to the Vaal Dam.

“There’s a hydroelectric power station on the Lesotho side, and water needs to run consistently through that plant to keep the turbines moving, so it runs consistently down into South Africa and the Vaal Dam, no matter how high or low the level of the Vaal Dam happens to be,” he said.

Source: Water Wise, Rand Water

Mathebula said that the governments of South Africa and Lesotho annually agree on the amount of water to be transferred.

“This year the agreement was for 780-million cubic metres to be delivered while generating 72 megawatts of hydropower through Lesotho’s Muela Power Station,” he said.

The stoppage of the LHWP has meant that there is a shortfall of 80-million cubic metres, which Mathebula said will be made up when the LHWP resumes in April 2025.

Phase II of the LHWP, now scheduled for completion in 2028, will impound the waters of the Senqu and Khubelu rivers in a dam called Polihali, adding approximately 2,325-million cubic metres in storage capacity to the LHWP. According to Holden, the LHWP will then be the biggest contributor of water to the Vaal River system.

“It is for this reason that the maintenance stoppage is so important. If it isn’t done it could result in a longer stoppage in the future, and if this happens in a drought year it could spell trouble. If people could focus on that, instead of this misinformed notion that Johannesburg doesn’t have enough water, we’d all be better off,” said Holden.

The Lesotho Highlands Water Project, which supplies water to Johannesburg’s urban highveld, is an engineering marvel, comprising several large reservoirs and one hydroelectric power station, all linked by rivers and long subterranean delivery tunnels. (Exclusive copyright David Southwood. Used with permission.)

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Next: Africa Oil Week: Mantashe slams “foreign-funded” activists

Previous: UCT vigil marks a year of war in Gaza

© 2024 GroundUp. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.

We put an invisible pixel in the article so that we can count traffic to republishers. All analytics tools are solely on our servers. We do not give our logs to any third party. Logs are deleted after two weeks. We do not use any IP address identifying information except to count regional traffic. We are solely interested in counting hits, not tracking users. If you republish, please do not delete the invisible pixel.