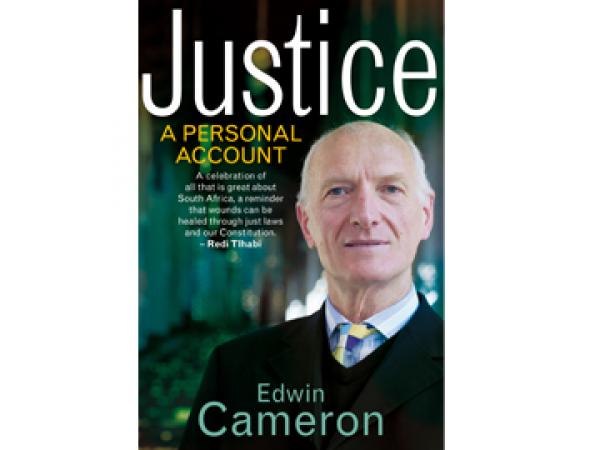

Justice: A Personal Account

Constitutional Court judge Edwin Cameron has published a new book, Justice: A Personal Account. It is a forceful defence of the rule of law and South Africa’s Constitution.

Cameron weaves stories from his life and legal career with historical cases to show how the law can support justice. He shows the progression of justice in South Africa from apartheid to the post-94 period.

The book starts with Cameron’s recollection of his father’s imprisonment. As a child he imagined Zonderwater prison to be a rehabilitation centre for alcoholics. This is why his father was sent there, the young Cameron optimistically believed. This was Cameron’s first encounter with the law, about which he pondered, “Was it only an instrument of rebuke and correction and subjection? Or could it be more? I did not know it then, but this vivid encounter imprinted and impelled my future life and career.”

The book is not blind praise-singing of the law and lawyers. Cameron describes miscarriages of justice too — and there are villains. For example, he tells of the case in 1971 when the dean of the Anglican Cathedral in Johannesburg was found guilty of terrorism and sentenced to five years in prison on the basis of dubious testimony by a police officer, despite very good lawyering by the dean’s advocate Sydney Kentridge. “It was said of [the judge] that he had never been know to disbelieve a senior police officer,” writes Cameron.

But the overall complex and compelling picture is of the development of a system of jurisprudence which supports justice not oppression. Indeed the dean was acquitted on appeal.

However, law has its limits. In the 1950s, Cameron explains, the courts delayed removing Coloured people from the voters’ roll for several years, but eventually the National Party dominated Parliament got its way.

This is an extract from chapter six, in which Cameron describes the difficult circumstances of his childhood. It does not deal directly with the law. Instead it deals with charity and its role next to political action. Cameron believes strongly in charity. He has been deeply influenced by Peter Singer’s views on the subject. Cameron emphasises that charity is not a substitute for political action and that if there was perfect social justice there would be little or no need for charity, but we do not live in that society and charity provides immediate relief.

Extract: A random act of kindness

Two years after Laura’s death, when Jeanie and I had returned to the children’s home in Queenstown, my mother moved back to Bloemfontein, where she had lived as a child and married my father, and where her daughters were born. She found a job in the municipality’s typing pool. She took it to be closer to us. The home provided only one train ticket a year, every December, for children to visit their families. Living in Bloemfontein halved the distance from Pretoria. This made it easier for her to travel down to Queenstown in the middle of the year to see us.

The December holiday after she moved, we spent with her, at her lodgings in a boarding house on Kellner Street. This was a few short blocks’ walk from where she worked in the city hall, a sandstone edifice on President Brand Street, directly across from the appeal court. That building’s monumental pillars and imposing pediment and facade impressed me, but I hardly thought about it. The lawyers who practised there, and the judges who decided cases inside it, seemed to occupy an unimaginably different world – a world of intellectual endeavour and of civic engagement and of respectability and of material abundance. I was not in any position even to dream of one day joining it.

Money was desperately tight. The removal and travel costs had to be repaid. My mother had no formal schooling beyond standard six (grade eight), and the municipality must have started her on the lowest grading for a white worker. Her salary was pitiably small. We spent a straitened Christmas, glad to be at home, away from Queenstown, but with no treats or frills. We went to no shops because there was no shopping to be done.

Jeanie and I played with the Wepeners, Anne and Richard and Martin, also home from Queenstown for December. They lived in a flat in Chembro House on busy Zastron Street. As often as we could, in Bloemfontein’s baking summer heat, we visited the municipal swimming baths at the top end of West Burger Street, in the lee of Naval Hill, where admission was two and a half cents. The Wepeners’ testy grandfather, who lived with them, would sometimes give us ten cents to see us through.

We lived unburdened by any sense of grievance or self-pity. On the contrary, we knew we were lucky. We had a roof over our heads, as my mother often reminded us, and beds to sleep in. And we ate every day, sparsely, but sufficiently. At the home in Queenstown, too, the ambience our supervisors cultivated was one of respectful gratitude – to the congregants who dropped money into the collection plates in Presbyterian churches across the country, helping to sustain the institution, and to the benefactors who over weekends would sometimes unexpectedly arrive at the gates to deliver cream cakes, or wooden boxes of soda drinks, for us to feast on.

Regularly we were reminded that many were far worse off than we were. And indeed we knew it. Far from decrying our circumstances, Jeanie and I focused our hopes on the future, in particular on my father. Though my mother had now divorced him a second time (the first was before I was born; they remarried shortly before we moved to Pietermaritzburg, when I was eighteen months old), skilled white artisans were in high demand (job reservation forbad training black artisans). Losing his job in Pietermaritzburg was surely what precipitated our family catastrophe. If he started work again, he would command a ready wage. If only Dad could keep a steady job, everything would change.

My mother kept us hopeful, too. She spoke of things on which she pinned her dreams. One was getting us out of the children’s home. Another was finding Daphne, the third daughter, given away in adoption in Bloemfontein in September 1951, before I was born, when she was just four months old. Where was she now? How was she? In the aftermath of Laura’s death, my mother pined unceasingly.

And then there was her dream of getting me into a ‘good’ school. It had to be one of the elite government boys’ high schools – Grey College in Bloemfontein, King Edward School in Johannesburg, which my father had attended until standard eight (grade ten), or Pretoria Boys’ High. Getting me a good education would change things. The future would be different. In the meantime, poverty in itself was no cause for complaint.

Then one day in January, just before Jeanie and I were due to return to Queenstown, something extraordinary happened. It was Jeanie’s thirteenth birthday, the twelfth of January, the day after my mother’s, the very day on which two years before Laura had met her death. Jeanie and I were at Kellner Street while my mother was at work. There was no money for any form of celebration. There was a knock at the door. Outside, in the hallway of the boarding house, stood a smartly dressed, attractive woman in her thirties or early forties. Expensively dressed and well made up, she exuded an air of polish. I remember her elegant shoes and handbag. I think she was wearing gloves. Her hair was pulled up and tied back in the style of the time.

Her manner belied her polish. It was diffident. She seemed slightly ill at ease, almost nervous. Hurriedly, she addressed me in Afrikaans. Was this where the Camerons lived? Yes, I said. She had something for us. Dankie, I said. She handed me a plain unaddressed envelope. Then she took her leave. The envelope in my hand, I watched her walk to the gate and drive off, without glancing back, in an expensive looking car.

I went inside and handed the envelope to Jeanie. We couldn’t contain our curiosity. We looked inside. Its sole content was a ten-rand note. We were amazed. Jubilant. Ten rands! We couldn’t believe what had befallen us. The note was crisp and crinkly to our touch. Who was the woman? Where was she from? How did she know us? And why had she done this? What could have led her to see so piercingly into our circumstances?

We had answers to none of these questions. All we knew was that a deliberate act of giving had intruded deep into our lives.

We waited, excited, for my mother to return from work. When she did, she shared our delight at the unexpected windfall, but she could cast no light on our questions. Apart from my account, we had no clues, and my mother could add nothing to the puzzle. So we turned instead to planning how to spend the money. There were many essentials my mother needed, and much that Jeanie and I needed, by way of clothes and toiletries and items for the new school year. For all of these, the money, as my mother put it, was a godsend.

But for now we postponed the practical necessities. Instead, we agreed that first we would visit a cake shop up the road. It closed only at 6, so there was time for Jeanie and me to get there. We chose a lavish cream cake. I still remember the cheer this brought us, carrying the cake delicately home, in its thin white cardboard cake box, and displaying it proudly on the table in the Kellner Street room, before tucking into it. We had a cake for Jeanie’s birthday!

The next day, when my mother went to work, she allowed us to go out to make further purchases, for the room and for our return to Queenstown. Jean and I walked around Bloemfontein’s shops with an air of excited capacitation. We could afford to consider, afford to choose, afford to buy.

I have no accurate notion of what the equivalent today of those ten rands is. But I remember the purchase of the cream cake required less than R2 – under one-fifth of the money. A similar cake at a home enterprise store today costs easily R80. On this calculus, the anonymous woman’s gift would today be worth four or five hundred rands. A website that calculates the effect of officially recorded inflation on nominal rand values suggests somewhat more – R686 in current values.

But my imagination jibs at how small both these sums seem. My mind wants the equivalent figure to come out in thousands, for the effect of those ten rands on our lives, and our spirits, was inexpressibly greater. Apart from transforming Jeanie’s birthday, and easing our material circumstances in much-needed practical ways, it left a residue that has deeply shaped my political consciousness.

My young life often benefited from charity. Soon after I gained admission to Pretoria Boys’ High, early one evening my mother and I received an unexpected visit at our flat in Sunnyside. It was one of the school’s administrators. He explained that he was a trustee of a discreet fund the school operated for needy families. I suspect he was directed to us by Hugo Ackermann, the maths and Latin teacher I encountered when I joined Form 2, who took me under his wing and became my guiding mentor, and whose whole family, including that of his older brother Laurie, later my colleague at the Constitutional Court, took me into its bosom.

That evening, the trustee gave my mother and me a small but welcome hand-out. I remember what we did with the money. We bought a second summer school shirt and a second pair of khaki shorts from the school’s officially designated shop in Paul Kruger Street; until then, we’d been rinsing out my only set overnight. From time to time over the next years, that gesture was quietly repeated. It enabled me to attend a school whose boys overwhelmingly came from the affluent upper-middle class homes of Brooklyn, Lynnwood and Waterkloof, without the potential embarrassment of patent need.

But what remains most deeply imprinted on my mind are not these later hand-outs, whose beneficence touched us through the anonymous mechanism of a fund. What lingers most vividly is the unnamed woman’s mysterious act of personal generosity. It left me deeply under the impression of how important acts of interventive kindness are.

“Charity is no substitute for political action … but there is no reason why charity cannot exist alongside political action.”

I appreciate the argument that, to remedy social injustice, charity is no substitute for political action. In the abstract, this is undeniable, but there is no reason why charity cannot exist alongside political action. Indeed, unless social justice can be realized instantaneously – and we know, sadly, that it cannot – benefaction now is as imperative as political change in due course.

The argument that charity is a diverting balm that soothes the need for change, and must thus be decried because it discourages radical political action, strikes me as absurdly abstract, indeed cruel. Of course we all need a good public education, and not charity, to help us out of poverty. That was my great good fortune, as a poor white youngster: to gain entrance to one of the country’s – perhaps one of the world’s – best government-funded schools. Of course we all need political and social incentives that provide tertiary education and generate jobs, rather than hand-outs. And I was privileged indeed, on the basis of my skin colour, to have access to education and job opportunities.

But I also got hand-outs – graciously given, most gratefully accepted hand-outs. Distributional interventions that changed my life. Their impact was intense and enduring. Until the practical benefits of good education, good opportunities and good jobs arrive for everyone – and in my case, they did, in time to make a difference to my life – we all need the caring and generosity of others. We all need gestures of the exhilaratingly practical and redemptive kind the nameless woman intruded onto my mother’s and Jeanie’s and my straitened lives in Bloemfontein in January 1963. More importantly, we need a government that, on behalf of all of us, expresses that loving care and concern toward our fellows. More specifically, we need a government that is constitutionally obliged to do so.

This is precisely what the Constitution gives us in South Africa.

Justice: A personal account is published by Tafelberg.

Foreword by Nelson Mandela.

ISBN: 978-0-624-06305-6.

The book is available for sale on Android devices here and on Kindles here.

The paperback will be available in South African book stores in March.

Review by Nathan Geffen.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Next: Strikers refuse to be misled

Previous: Khayelitsha police overburdened says “honest cop”

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.