Shaggy sheep, ice rats and the future of Joburg’s water supply

Crucial wetlands in the Lesotho Highlands are in trouble

Erosion in Lesotho’s rugged river valleys threatens the livelihoods of Basotho herders, and poses a water security risk for the Southern African region. Photos: Sean Christie

Gauteng depends on the Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP) for the bulk of its water, but researchers say there is a problem: wetlands crucial to the regulation of the water that enters Lesotho’s dams are collapsing, and not enough is being done to arrest their degradation.

“The degradation of montane and alpine wetlands in the Maloti-Drakensberg region of South Africa and Lesotho is likely one of the greatest threats to water security in water-scarce Southern Africa,” says South African soil science specialist Johan van Tol.

A study has noted the disappearance of approximately 21 to 24% of wetlands in the Mohale and Katse dam catchments between 1995 and 2014.

Lesotho-based ecologist Peter Chatanga says the wetlands found in the Lesotho Highlands are mostly palustrine wetlands, “meaning they are able to support vegetation”.

“These wetlands slow the flow of the water downstream, which helps to regulate soil erosion, which in turn helps to prevent sedimentation in the dams of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project. This is a huge contribution to the sustainability of the LHWP,” he says.

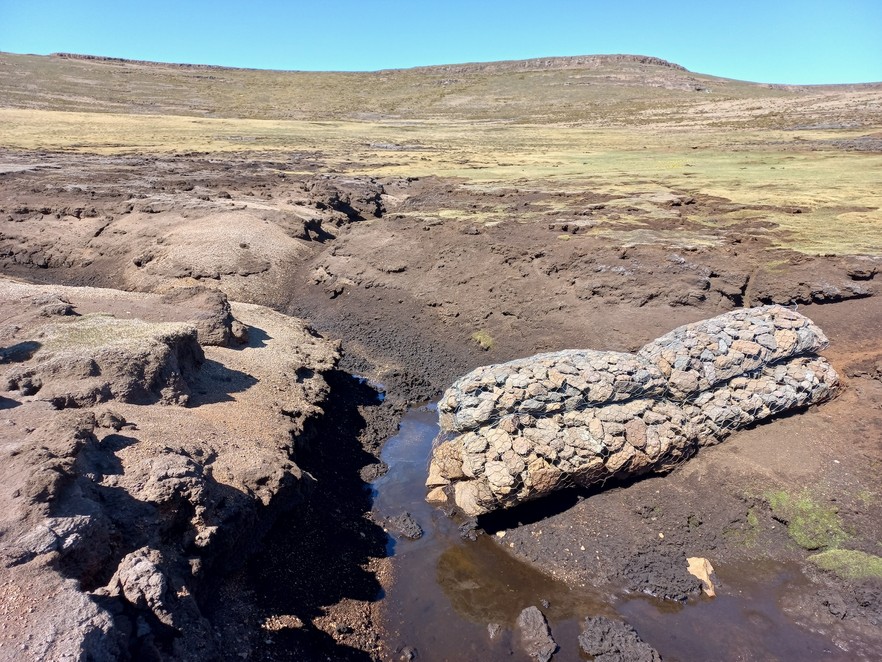

Healthy peat wetlands act like sponges, soaking up water and releasing it slowly and regularly. When peat wetlands become degraded, like the Lesotho Highlands wetland pictured here, a channel opens up, and water quickly drains out.

Complex causes

There is broad agreement that wetland loss and degradation plays a major role in dam sedimentation in Lesotho. But according to Chatanga the causes of wetland degradation and loss “are many, complex, and interactive”.

He lists communal grazing as one.

“It’s a free-for-all in the river catchments of the Highlands. If you go up there with your animals, no one will ask you what you are doing. All land has a carrying capacity, and in the absence of regulation this will be exceeded and that is what is happening,” says Chatanga.

Overgrazing in the Lesotho Highlands is often cited as the major cause of wetlands degradation.

Improved accessibility to the Highlands is also a factor.

“In the past there was limited accessibility to a lot of the wetlands, but recently as a result of the LHWP there has been a lot of development including the building of good roads. This is good for the economy, but it increases the anthropogenic [man-made] pressures on those wetlands,” Chatanga says.

Improved accessibility to the Lesotho Highlands has resulted in development. Many projects have been executed without any Environmental Impact Assessment being done, including Afriski, a ski resort under Mahlasela Peak.

On a recent trip to the river valleys of the Malibamatso and Tshelenyana rivers (the main rivers feeding into Katse reservoir), GroundUp interviewed several herders who said they had driven their sheep up into the river valleys from the shoreline of the Katse Dam, a journey of four to five days. In the 2022/3 annual report of the Lesotho Highlands Development Authority (LHDA), the displacement of flocks by the inundation of the LHWP’s dams is cited as the main cause of wetlands degradation in the Lesotho Highlands.

Today, many wetlands in the Lesotho Highlands are inhabited by a species of rodent called Sloggett’s ice rat (Myotomys sloggetti). According to Chatanga, ice rats are an indicator of wetland degradation.

Ice rats burrow in the wetlands of the Lesotho Highlands, and when their tunnels collapse a gulley is formed, hastening the demise of the wetland. Photo: Johan van Tol

“They generally affect wetlands that are already somewhat degraded but once they get in they cause further degradation. They are burrowers, and when water floods the wetland it flows through those burrows, causing the top part to fall in, and the moment it falls, it forms a gulley,” says Chatanga.

According to LHDA spokesperson Mpho Brown, “Ice rats are a secondary impact, and when the primary concern of livestock overgrazing is addressed, the ice rats situation should reverse”.

Problematic interventions

After failing to commission an Environmental Impact Assessment ahead of the construction of the Katse Dam, the LHDA took steps to address environmental issues in LHWP’s river valleys in the early 2000s, implementing a set of soil conservation programs under a programme called Integrated Catchment Management.

The impact of the interventions is much debated, however.

According to Brown, the interventions are working.

“Wetlands and rangeland health condition assessments done under our in-house monitoring programs confirm improvement in terms of the indicators we monitor. There is tangible photographic and visual evidence of these which a site visit would be able to confirm,” he says.

However, Phallang Lebesa, a former LHDA officer who worked on several wetlands’ restoration projects in the Lesotho highlands, says many of these have since failed.

“The main objective is typically to block the erosion channel that is draining the wetland. In the past we mostly attempted to do this with gabion baskets and other structures, but if you visit those sites today you will see that the water has simply bypassed those barriers and created new channels, and in some cases the wire from the gabions has been removed by herders, who use it to reinforce the kraal walls at their cattle posts,” Lebesa says.

Chatanga says gabions have been effective in improving the health of certain wetlands, but many interventions appear to have been implemented without analysis of the causes of problems.

Many wetlands restoration interventions have failed, says a former employee of the Lesotho Highlands Development Authority. This gabion basket in a wetland in the catchment of Polihali Dam was meant to block the erosion channel that is draining the wetland, but a new channel has bypassed the structure.

For Van Tol, the absence of baseline research on the possible causes of wetland degradation is alarming, as is the absence of studies quantifying the success of the interventions.

“There is a wealth of literature addressing the state of wetlands in the Maloti-Drakensberg but there are actually very few detailed baseline studies covering soils, vegetation, the extent and rate of degradation, and so forth. In the absence of baseline studies, it is unsurprising that interventions fail,” he says.

Van Tol is one of several researchers working on the Mount-aux-Sources Long Term Socio-Ecological Research platform, founded in 2022.

“Instead of sitting back and criticising the work that is being done currently, the aim is to do some of those missing baseline studies, so that appropriate interventions can be designed. These interventions should go beyond merely treating the symptoms and focus on improving the management of terrestrial land through better grazing practices and the restoration of both wetland and terrestrial soils,” he says.

A water monitoring station on the Malibamatso River, which feeds into Katse, the largest of the LHWP’s dams. Information on river and dam sedimentation in Lesotho is hard to come by.

How serious is the LHWP’s sedimentation problem?

The rate of sedimentation in Lesotho’s dams is a matter of some debate. The LHDA, responsible for the dams and catchments, does not regularly publish data on sedimentation levels.

The LHWP consists of two large dams called Katse and Mohale, a smaller reservoir called Muela and the Matsoku Weir, which transfers water from the Matsoku River into the Katse Dam via an eight-kilometre tunnel. A third large dam called Polihali is scheduled for completion in 2028.

Sediment surveys for Muela reservoir conducted in 2003 and 2019 on behalf of the LHDA produced alarming findings. The first, conducted just six years after the completion of the dam, found that the dam was 7% full of sediment, a figure that had risen to 12% by 2019.

“The rate of sedimentation in Muela is 0.5% a year,” says Brown, who confirmed that the sedimentation in the catchments of the LHWP is a concern.

Muela reservoir serves as a tailpond for the Muela underground hydroelectric power station that generates electricity to supply the needs of Lesotho. The water it releases flows directly into South Africa via a 38km tunnel.

In a 2017 report in the Lesotho Times, Reentseng Molapo, the LHDA manager responsible for maintaining the infrastructure of the LHWP, warned that sedimentation in Muela Dam, resulting from soil degradation upstream, had the potential to shut down the entire LHWP.

Sedimentation of Matsoku is so advanced that engineers have had to cut a channel through the silt that has banked up against the weir, to allow water to flow to the intake works of the tunnel (viewable on Google Earth).

According to Brown, an estimated 1.4% of Katse capacity has been lost to sediment since the dam was flooded 28 years ago, and the amount of sediment in Mohale dam is estimated at 0.8% to 1.3%. Polihali will likely lose 5% of its storage capacity in the first 50 years of its life, and 10% within a hundred years, according to a 2018 modelling study.

South African water specialist Ricard Holden says these numbers are “quite small”, and “sedimentation is not an immediate problem for the project’s end users.”

Herders from the area around Katse Dam have been pushed into the river valleys of the Lesotho Highlands as their former rangelands are now under water.

Erosion and sedimentation is an issue on the South African part of the LHWP, too, especially along the Ash River, which carries water from Lesotho into South Africa, and in Sol Plaatjie Dam near Bethlehem, where, according to the Trans Caledon Tunnel Authority (TCTA), which looks after the South African side of the LHWP, the silt delta has expanded significantly.

In October, water flows through the LHWP were stopped at Katse to enable critical repair work to be done. Water is scheduled to resume flowing in April 2025. According to TCTA spokesperson Wanda Mkutshulwa, erosion scoping and repairs “along about 26 kilometres of the Ash River, fences, gates and gabions on the Caledon River”, is part of the work that will be done during the six months stoppage of the LHWP.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Next: Development of Tshwane settlement stalled by power struggle

Previous: Elderly Ga-Rankuwa residents march to demand tarred roads

© 2024 GroundUp. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.

We put an invisible pixel in the article so that we can count traffic to republishers. All analytics tools are solely on our servers. We do not give our logs to any third party. Logs are deleted after two weeks. We do not use any IP address identifying information except to count regional traffic. We are solely interested in counting hits, not tracking users. If you republish, please do not delete the invisible pixel.