A strike turned violent. The company fired the workers. Here’s what the Concourt ruled

Ruling has implications for the legal concept of derivative misconduct

On 22 August 2012 a group of Dunlop employees started a protected strike that soon turned violent. Despite an interdict and the intervention of the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa at the time, the violence escalated. On 26 September 2012 all the employees who participated in the protected strike were dismissed.

The question that arose was whether Dunlop was entitled to dismiss those employees that they could not prove were present during the violence. For unknown reasons, these employees chose not to defend themselves against the dismissals during arbitration. The CCMA held that Dunlop did not prove “on a balance of probabilities” that strikers who were not involved in or present at the violence, knew who the perpetrators were. The arbitrator rejected Dunlop’s argument that if these strikers had reason to defend themselves against dismissal, they would have come to the CCMA to do so. So the CCMA ordered their reinstatement.

The Labour Court and the Labour Appeal Court disagreed with the CCMA. Both held that, on the one hand, the circumstantial evidence was enough to place all the strikers at the scene of the violence and, on the other, that the employees should have come forward either to identify the perpetrators of the violence or to explain that they were not present. By not doing so, the Labour Court held, they were guilty of “derivative misconduct” by breaching the duty of good faith that an employee has towards her employer.

But does this mean that an employee, who happens to merely be present where misconduct occurs, has a duty to either exonerate himself or disclose information about other employees participating in the misconduct – and that failure to do so is grounds for dismissal?

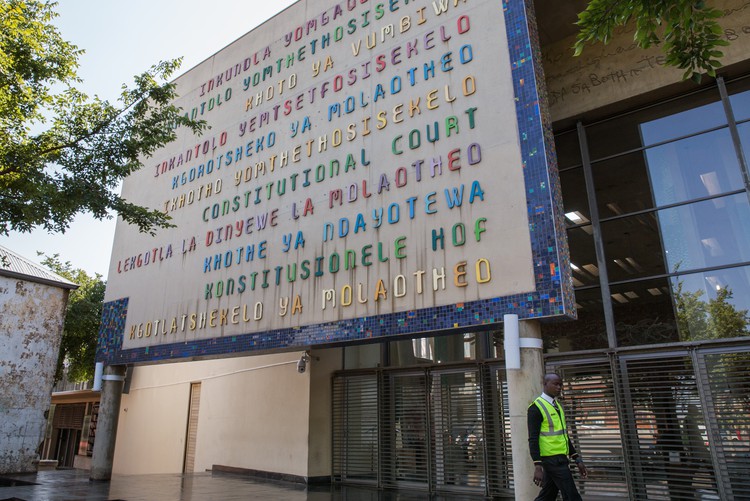

The case was heard in the Constitutional Court in February and a ruling was made last month.

NUMSA, on behalf of the Dunlop workers, appealed their dismissals arguing that, even if their presence at the violence could be assumed, they could only have a duty to provide information about the events or to exonerate themselves if Dunlop, as the employee, had guaranteed their safety. The duty of good faith between the employer and employee, they argued, is a two-way street.

Justice Froneman, writing a unanimous decision, cautioned against the use of the principle of “derivative misconduct”. Following submissions by the Casual Workers Advice Office as amicus curiae, the court held that the principal was developed as a solution to the problem of employers being unable to positively identify all the participants in group misconduct such as a violent strike.

The principle of derivative misconduct means that the employer can still dismiss workers not identified as participants for not disclosing information about the employees who were participating. This means that it might be easier to dismiss people not involved in violent misconduct than those who actually were involved.

The court also questioned the principle that there was a duty for an employee to disclose information about the misconduct of fellow employees flowing from the duty of good faith between an employee and an employer.

In a unanimous judgment, Justice Froneman wrote that we should be careful how we use words like “trust”, “good faith” and “confidence” in an employment relationship. The good faith and trust that an employee must show an employer cannot mean that an employee is never entitled to act in their own interests, even if it is contrary to the interests of the employer. In other words, an employee who chooses not to speak out against a fellow employee (in their own interest or in the interest of worker solidarity, for example) or not to exonerate themself is not necessarily guilty of acting in bad faith and therefore breaching a duty towards the employer.

This is particularly the case with strikes. “To expect employees to be their employer’s keeper in the context of a strike where worker solidarity plays an important role in the power play between worker and employer would be asking too much without some reciprocal obligation on an employer’s part,” wrote Froneman.

The Court upheld NUMSA’s appeal on behalf of the workers not positively identified as being present at the violent protests. The workers who did participate in the violence were dismissed by Dunlop for misconduct in 2012 as is permitted by the Labour Relations Act. Their dismissals were not appealed.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Next: “We don’t grow plants, we grow people”

Previous: Gauteng wants blanket court interdict on land occupations

© 2019 GroundUp.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.