When can a landlord evict law-abiding tenants to renovate?

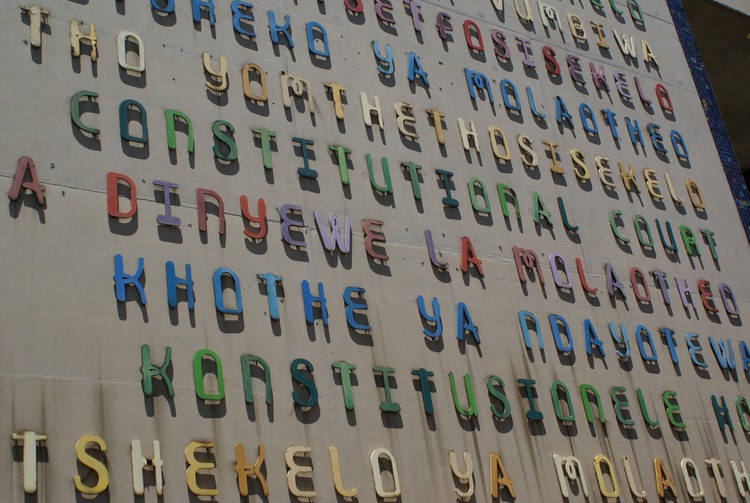

More than 50 tenants of a derelict building in Hillbrow have taken their landlord to the Constitutional Court

When can a landlord evict law-abiding tenants in order to effect refurbishments? And when can a landlord evict tenants for this reason on an urgent basis? These two questions are currently before the Constitutional Court in an application for leave to appeal an eviction which was ordered by the High Court on 23 May 2018.

Background

The case concerns the fate of more than 50 tenants of a derelict building in Hillbrow, some of whom have lived on the property for as long as 25 years.

The buildings are owned by Lewray Investments and managed by Urban Taskforce Investments.

The building which forms the subject of the dispute was erected in 1954. It is currently in a poor condition and in need of refurbishment. This is not disputed by any of the parties.

What is in dispute however, is what process must be followed to effect refurbishments and what the respective rights of the tenants and landlord are in these circumstances.

In January 2018, the landlord provided the tenants with a notice to vacate the property, so as to do the refurbishments. In the notice, the landlord offered to relocate the tenants to another building which it owns. Alternatively, it offered the tenants a R5,000 cash payment as compensation.

The tenants interpreted the notice as an eviction notice and referred a dispute to the Rental Housing Tribunal.

According to the Constitution a person cannot be evicted without a court order. A landlord must follow the procedure set out by the Prevention of Illegal Eviction and Unlawful Occupation Act (PIE Act).

The Rental Housing Tribunal made its ruling on 5 March 2018. The Tribunal ruled that the landlord’s notice was merely a notice to vacate the property and not an eviction notice. It also found that the notice provided the tenants with two options. Their first option was to vacate the property in which case they would be entitled not to pay rent for that period. Alternatively, they could remain on the property, but this would mean that they would have no claim for damages should they sustain injuries or damage during the refurbishment. The Tribunal also said that should the tenants choose to vacate the property, the landlord must provide them with alternative accommodation and offer them the sum of R2,500 as compensation.

After the Tribunal’s order, the landlord sent another notice to the tenants. This time it instructed the tenants to vacate the property immediately. The tenants refused to vacate. The landlord then approached the High Court on an urgent basis to evict the tenants. The High Court granted this order on 23 May 2018. The tenants applied for leave to appeal, but this was refused by the Court. They then approached the Supreme Court of Appeal for leave to appeal but this application was also rejected.

Urgency

In a last effort to set aside their eviction, the tenants approached the Constitutional Court for relief. In their papers they raise two main arguments. First, that the High Court applied the wrong procedure for urgent evictions. Secondly, that the eviction is improper because it circumvents the PIE Act and related regulations.

The tenants argue that the High Court applied the incorrect procedure for urgent evictions. This is because the PIE Act requires, amongst other things, that the property pose a real and imminent danger of substantial injury to person or property. Although the building was in a poor condition this and other requirements in the PIE Act were not met. The tenants argue that the High Court conceded this, but instead of applying this test, which is set out in Section 5 of the PIE Act, the High Court applied the test for urgent applications, which is set out in the High Court rules.

The tenants argue that the High Court’s approach has grave consequences for poor and vulnerable tenants. This is because in adopting this approach, the High Court accepted financial expediency as a basis to grant an urgent eviction. The tenants argue that this infringes their constitutional rights and urgent evictions may only be granted under the strict circumstances laid down by the PIE Act.

Improper Eviction

The second main argument the tenants raise is that the eviction violated the Gauteng Regulations to the Rental Housing Act. These regulate when tenants may be evicted in order to make refurbishments.

The tenants highlight a few elements of the regulations. First, they only permit the landlord to cancel the lease and evict a tenant if the property is uninhabitable. Second, they give the tenant the right to return to a property of the same size when the refurbishments are complete. Third, the regulations provide that the tenants are entitled to not pay rent during the period of refurbishments. The tenants argue that the regulations try to bridge the power imbalance between poor and vulnerable tenants in derelict buildings and powerful landlords.

The tenants argue that the High Court violated the Regulations and the PIE Act in three ways. First, the High Court erred by finding that the tenants were “unlawful occupiers” in terms of the PIE Act and could therefore be evicted. This contravenes the PIE Act because it defines an unlawful occupier as someone who has no legal right to be on the property. However, it was common cause that the tenants had paid all their rent which was due and the lease had not been cancelled.

Second, the High Court acknowledged that the landlord intended to destroy the current flats and sub-divide them. So the tenants right to return to the same property would be violated because they would be returning to smaller units.

Third, the High Court refused to stop the tenants’ rent during the refurbishment period as required by the regulations.

Relief Sought

The tenants argue that the eviction should be set aside and the tenants must be housed in units of the same size and be entitled to a remission of rental.

The landlord’s arguments

The landlord argues that the question of the correct test for urgency is moot because the tenants have already been relocated following a consent order granted on 8 September 2018. As far as the question of the regulations and not having to pay rent go, the landlord argues that the Rental Housing Tribunal and not the Constitutional Court is best tasked to resolve this question. This is because the question of whether a landlord may evict tenants to make refurbishments involves complex technical and economic issues that the Tribunal is best tasked to answer. The landlord also argues that to make a return on its investment it is obliged to sub-divide the units; it is not economically viable to keep the units the current size.

Why this case is important

This case raises important questions about the competing interests of landlords and tenants in derelict buildings in Johannesburg. This is an issue not only in Johannesburg but for cities across the country. As activists and communities fight against gentrification and urban renewal, the question of how these competing interests should be resolved is one the courts must urgently answer.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Next: Informal miners risk their lives to make R25 from a wheelbarrow of coal

Previous: Housing activists build shacks on prime inner-city land

Letters

Dear Editor

If a body corporate has a strong active membership and ensures that all tenants pay their rates, levies at the end of the month, then a building should not fall into rack and ruin. If it has fallen into rack and ruin then the Tenants are to blame,not the Landlord. Who is benefiting from this? Only the courts, lawyers and attorneys. It is enough to make one sick to see how unjust the courts are.

© 2018 GroundUp.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.