Why is the Public Investment Corporation bankrolling private education for the rich?

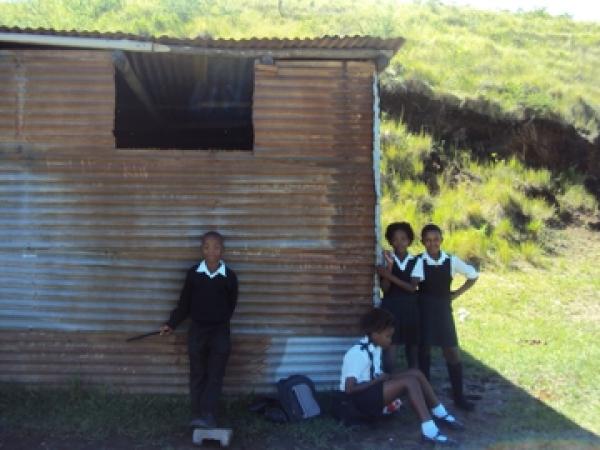

Next month young activists will attempt to make Bhisho the centre of the world. Members of Equal Education (EE) will be present throughout the duration of a court case aimed at securing infrastructure standards for every school in South Africa.

If the case is won, significant public resources will be needed to electrify the 3,600 schools lacking electricity, to supply water to the 2,400 schools currently without it, and to provide libraries to over 20,000 schools. That considerable investment in school infrastructure is needed–along with accountable and efficient management of that investment–is understood by everyone. Research done by EE has shown that it would cost R333 million to put a library in every public school in Gauteng. It has therefore raised eyebrows that the Public Investment Corporation (PIC) has invested R360 million in a chain of private schools aimed at upper-middle income families.

The Curro Private Schools company describes itself as a “Christian-based educational institution” which “focusses on the acquisition, development and management of private schools”. The company sees itself as “relieving pressure on the government” by expanding school capacity. It also claims to achieve a 100% pass rate, and to contribute to society by offering a number of bursaries to poor students.

The company currently has 12,500 children in 22 schools. CEO Chris van der Merwe says, “By 2015-16 we are hoping for 40 schools. Our ultimate target is … for 80 schools by 2022. I think 80 schools will give us 80,000 – 90,000 learners.”

For the proprietor this kind of private schooling is big business. Van der Merwe’s remuneration in 2010 was R908,000. At that time he owned around 4% of the company, which at today’s share price would give him an ownership stake worth over R52 million.

The Curro schools operate a range of different brands at different prices. The Meridian schools – also operated by Curro – cater to a slightly lower segment of the market. The schools are not targeted at the very rich, but the fees are still significant. A grade one learner at a Meridian school will pay approximately R750 per month, and a grade twelve approximately R1500 per month. At a Curro school the fees rise to approximately R2000 per month for grade one, and R3800 per month for grade twelve. At Curro Durbanville for example, grade twelve in 2012 would have cost around R40,000. In addition, the once-off enrollment fees can be upwards of R6,000.

The right to operate a private school is guaranteed in the Constitution. Section 29(3) says that “[e]veryone has the right to establish and maintain, at their own expense, independent educational institutions” provided that they are registered, maintain comparable standards to public institutions and “do not discriminate on the basis of race”. Subsection 4 adds, “Subsection (3) does not preclude state subsidies for independent educational institutions.”

The right is there, but a different question is whether this is an appropriate investment by the Public Investment Corporation. The PIC manages assets valued at R1.17 trillion as at 31 March 2012, making it one of the largest investment managers on the African continent. Its clients are public sector entities, most of which are pension, provident, social security, development and guardian funds. For example, the public sector teachers have millions invested with the PIC through their pension funds. The PIC is wholly owned by the South African government, with the Minister of Finance as shareholder representative. One of its objectives is to make profit for its shareholders. Another is to contribute to the development of South Africa.

Some may understandably say that given the malaise in public education, any alternative, for at least some South African children, is desirable. Currently just over 5.2% of schools in South Africa are private, and these cater to just 3% of learners, so it is not, at this stage, a massive trend. Interestingly though 19% of schools in Gauteng are private schools. In fact, there are more private schools than no-fee public schools in Gauteng. Perhaps this portends a future education system increasingly divided by what one can afford.

So is the public funding of private schools good public policy? What is the trajectory of this approach and where does this policy lead? What is the overall social impact in the short, medium and long term of increasing private education, with or without state support? And should a state body be investing in a private institution that promotes a specific religion?

Some of the answers are obvious. Private schools draw families from significantly or slightly more affluent families out of public schools. This leads to parents who might have professional or other skills not being available for School Governing Bodies in public schools. Students in public schools do not get the academic benefit of being in classes with slightly more affluent learners. Society is stratified and public schools lose their role as places where social cohesion is built. Inequality is less likely to be ameliorated through the education system. Teachers may be drawn out of public schools. In many instances their training was subsidised, if not paid for, by the state. And in respect of those public schools that charge fees, when students move from these to private schools the public school system also loses that fee income.

The society envisioned by the Constitution requires participation in a strong public education system that brings the young people of South Africa together. The Constitution requires us to “heal the divisions of the past” and “build a united and democratic South Africa”. This has implications for how we structure our education system.

In my view, therefore, the PIC should not be invested in profit-making schools aimed at a relatively affluent sector of the population. The PIC and all state entities should be serving the needs of the majority of citizens. It is clear though that demand for private education will only grow unless and until the daily crisis of our public education system is addressed.

Isaacs is the Deputy General Secretary of Equal Education. You can follow him on Twitter @doronisaacs.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Next: Sunset in Sea Point. Photo by Mary-Jane Matsolo.

Previous: Understanding the Simelane judgment

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.