Zimbabwean children miss exams as Home Affairs sends them from city to city

“These people are not considerate. Why work with refugees when they do not have refugees’ interests at heart?”

Three Zimbabwean refugee children aged 7, 12 and 14, have been out of school for two weeks and missed examinations because they had to travel from Johannesburg to Cape Town to renew their refugee status. The Pretoria Home Affairs office refused to serve them because they originally applied for asylum in Cape Town. And their overnight trip to Cape Town became ten days, as they tried to navigate the Home Affairs bureaucracy.

Before the family left for Cape Town on 22 May, their school threatened to deregister the children because they had been absent for two days trying to get their documents renewed at Pretoria Home Affairs. “If they are not back to school within ten days, we will deregister them,” the mother was told.

On Wednesday, 23 May at about 4am Nyarai (not her real name) arrived at Home Affairs on the Cape Town Foreshore. An official told her that Zimbabweans are only served on Mondays, Tuesdays and Fridays. But the official also said that Friday, 25 May was not an option because the building was going to be fumigated.

Nyarai tried to negotiate with the official, explaining that she needed help urgently. She explained that she didn’t have family in Cape Town, nor money for food and accommodation for such a long period of time. But, she says, the official refused to listen to her story. “We don’t care about your story that you are from Joburg. It’s not our problem … we don’t want to hear it,” Nyarai says the official told her.

She also told the official about the school’s threat to deregister the children, hoping that he would offer her a formal letter for the school. But the official said the document she was going to be issued was her proof. “I became emotional and burst out in tears. Why are these people not considerate? Why work with refugees when they do not have refugees’ interests at heart?”

Nyarai had to hitchhike to Cape Town because she didn’t have enough money for bus fare. “I am a single parent. I work as a hairdresser and the only days I make money are the last three days of the month, which I already spent here in Cape Town. I rent a hairdresser’s chair for R2,500. I need to pay for our [home rent], buy food and pay school fees,” she said.

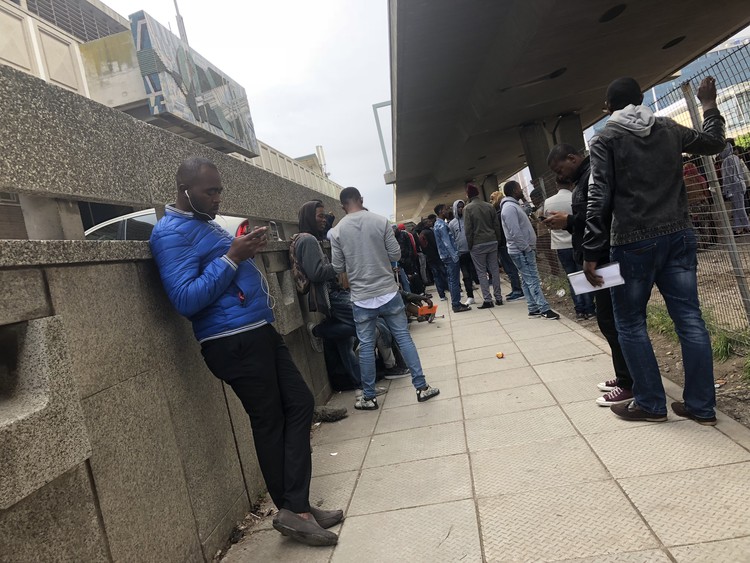

When she returned on Monday, 28 May at about 4am the queue was already long. The official then said there were too many people and gave them appointment dates. She was given an appointment for 31 May.

On 31 May at about 2pm she was finally served, but with a notice of intention to withdraw her refugee status. She has 30 days to appeal. “This means I have to travel back to Cape Town again at month end. I was told that because I travelled to Zimbabwe in 2007 I invalidated my refugee status.”

Nyarai said she fled persecution in Zimbabwe. “Before the 2005 parliamentary elections, ZANU PF leaders would come and recruit young girls and boys, forcing us to sing liberation struggle songs and do slogans. Youths in the same area were also forced to join a national youth service. When I refused to join the national service I was shamboked. I then crossed to South Africa through Beitbridge border. My wounds were still fresh when I sought asylum.”

Last month Home Affairs spokesperson Thabo Mokgola told GroundUp that children are prioritised at the Foreshore office. He also said that applicants who can show proof that they are travelling are prioritised.

Anthony Muteti of Voice of Africans for Change said, “It is an unfortunate incident that clearly shows how insensitive Home Affairs officials are. This runs contrary to their principle of Batho Pele.”

Home Affairs has been taken to court a number of times over its policy of only serving asylum seekers and refugees in the centres where they originally applied.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Next: M.I.A. brings colour to the Old Biscuit Mill

Previous: Meet Adriaan du Toit, the “independent” geologist who trolls environmentalists and Cyril Ramaphosa

© 2018 GroundUp.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.